The quest to construct the world's most powerful ground-based observatories has reached a critical juncture, with astronomers making a compelling case for establishing a 30-meter class telescope in Europe's Canary Islands. A comprehensive white paper authored by Francesco Coti Zelati from Barcelona's Spanish Institute of Space Sciences, along with his colleagues, presents a scientifically rigorous argument for situating this astronomical giant at the Roque de los Muchachos Observatory on La Palma—a decision that could reshape our understanding of the northern celestial hemisphere for decades to come.

The fundamental principle driving modern telescope design is elegantly simple yet profoundly consequential: aperture determines capability. Larger telescopes capture more photons from distant cosmic sources, enabling astronomers to peer deeper into space and further back in time. This relationship between size and observational power has made the construction of extremely large telescopes a paramount priority for the global astronomical community. However, the path to realizing these ambitious projects involves navigating complex challenges that extend far beyond engineering and financial considerations—encompassing cultural sensitivity, geographical constraints, and international scientific cooperation.

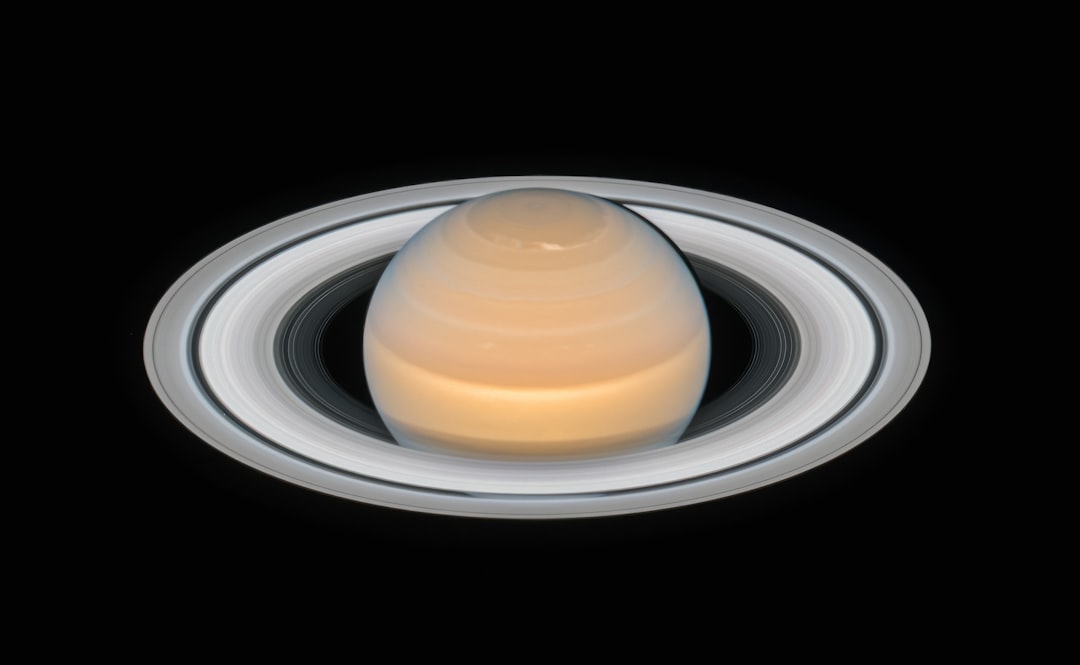

The northern hemisphere currently faces a significant observational deficit. While the southern skies will soon be surveyed by revolutionary instruments like Chile's Extremely Large Telescope (39 meters) and the Giant Magellan Telescope (25 meters), the north lacks comparable infrastructure. This asymmetry leaves iconic celestial objects like the Andromeda Galaxy and the Triangulum Galaxy—along with vast swaths of the northern sky—without access to the transformative observational capabilities that 30-40 meter class telescopes provide.

The Evolution of Multi-Messenger Astronomy

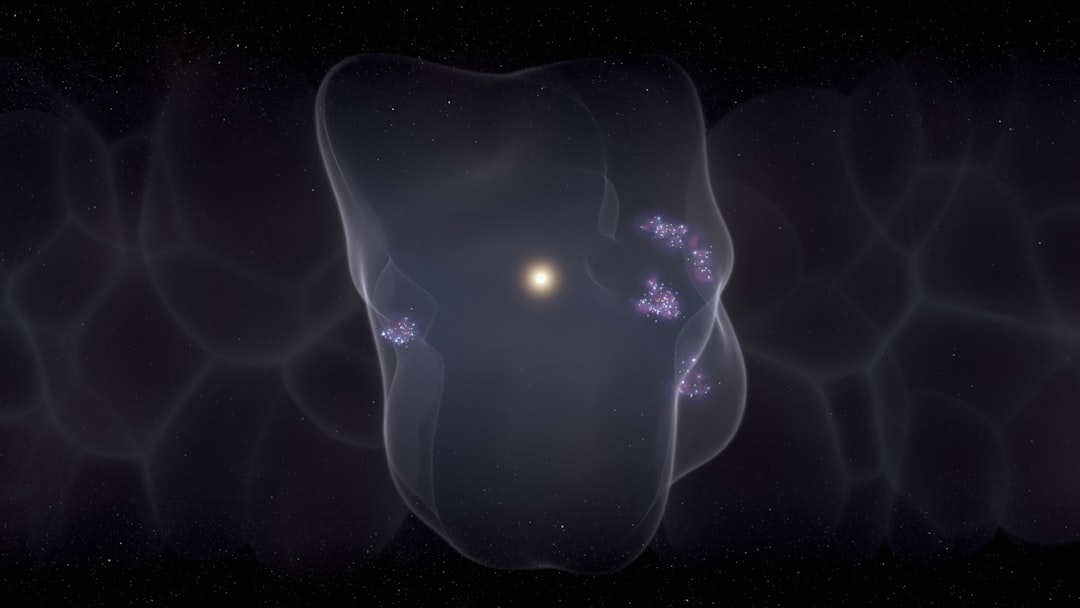

The urgency for a northern hemisphere giant telescope has intensified with the emergence of multi-messenger astronomy—a revolutionary paradigm that coordinates observations across different types of cosmic signals. When gravitational wave detectors like LIGO identify cataclysmic events such as colliding black holes or merging neutron stars, they trigger a global network of telescopes to immediately observe the same region of space. These follow-up observations must occur within minutes or hours to capture the fleeting electromagnetic signatures that accompany these extraordinary phenomena.

The next generation of gravitational wave observatories—including Europe's Einstein Telescope and America's Cosmic Explorer—will detect events at unprecedented distances and sensitivities when they come online in the late 2030s. However, without a corresponding optical and infrared telescope of sufficient size in the northern hemisphere, astronomers will be unable to conduct comprehensive follow-up studies of many detected events. This represents not merely an inconvenience, but a fundamental gap in our observational capabilities that could cause us to miss crucial scientific discoveries.

"The scientific imperative for a northern hemisphere 30-meter class telescope has never been more urgent. As we enter the era of gravitational wave astronomy and time-domain astrophysics, the absence of such an instrument creates an observational blind spot that compromises our ability to understand the most energetic events in the universe," explains Dr. Zelati's research team in their white paper.

A Decades-Long Journey From Concept to Controversy

The Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) project emerged from early 2000s planning efforts, with formal establishment in 2003 as an international collaboration involving institutions from the United States, Canada, Japan, China, and India. After extensive site testing and evaluation, project leaders selected Mauna Kea, Hawaii as the optimal location in 2009, citing its exceptional atmospheric conditions, high altitude (4,050 meters), and existing observatory infrastructure.

However, the 2014 groundbreaking ceremony triggered immediate and sustained opposition from native Hawaiian cultural practitioners who consider Mauna Kea sacred. The mountain, known as Mauna a Wākea in Hawaiian, holds profound spiritual significance as the dwelling place of deities and ancestors. Protesters argued that constructing another large telescope on the already crowded summit would constitute further desecration of sacred land. This conflict brought construction to an immediate halt and initiated a legal and cultural battle that has persisted for over a decade.

The controversy surrounding Mauna Kea reflects broader tensions between scientific advancement and indigenous rights—issues that the astronomical community has increasingly recognized must be addressed with genuine respect and meaningful consultation. While some astronomers initially viewed the protests as obstacles to scientific progress, many have come to understand the legitimate concerns of Native Hawaiians and the need for more thoughtful approaches to observatory siting.

The La Palma Alternative: A Strategic Pivot

By 2019, with no resolution in sight at Mauna Kea and mounting frustration over project delays, TMT leadership identified La Palma in the Canary Islands as a viable alternative site. While the atmospheric seeing conditions at La Palma are slightly inferior to those at Mauna Kea—a critical parameter for achieving the sharpest possible images—the location offers numerous compelling advantages that extend beyond pure observational metrics.

The Roque de los Muchachos Observatory already hosts an impressive array of telescopes, including the 10.4-meter Gran Telescopio Canarias—currently Europe's largest optical telescope. This existing infrastructure means that essential support systems, including power, communications, and maintenance facilities, are already established. Additionally, the Canary Islands have implemented rigorous dark sky protection regulations, ensuring minimal light pollution that could compromise observations.

Another strategic advantage involves temporal coordination with southern hemisphere observatories. La Palma's location, approximately four hours ahead of Chile in local time, facilitates seamless handoffs when monitoring transient astronomical events. As objects move across the sky due to Earth's rotation, observations can transition smoothly from southern to northern hemisphere telescopes, providing continuous coverage of time-critical phenomena.

Scientific Capabilities and Technical Specifications

The white paper submitted to the European Southern Observatory's "Expanding Horizons: Transforming Astronomy in the 2040s" initiative outlines the transformative scientific capabilities that the TMT would bring to La Palma. The telescope's 30-meter primary mirror—composed of 492 individual hexagonal segments working in concert—would collect nine times more light than current 10-meter class telescopes, enabling observations of objects that are currently beyond our reach.

Key technical features highlighted in the proposal include:

- Ultra-fast photometry systems: Capable of capturing extremely rapid variations in celestial brightness, essential for studying phenomena like pulsar emissions, stellar flares, and the explosive deaths of massive stars

- Wide wavelength coverage: Instruments spanning from ultraviolet through visible light to near-infrared wavelengths, providing comprehensive spectral analysis of astronomical targets

- Adaptive optics capabilities: Advanced systems that compensate for atmospheric turbulence in real-time, delivering images approaching the theoretical diffraction limit of the telescope

- High-resolution spectroscopy: Enabling detailed chemical composition analysis of distant stars, galaxies, and the intergalactic medium

- Time-domain astronomy optimization: Rapid response capabilities for observing transient events detected by gravitational wave observatories and other alert systems

Bridging the Observational Gap in Time-Domain Science

The paper emphasizes that time-domain astronomy—the study of how celestial objects change over time—represents one of the most rapidly advancing frontiers in astrophysics. Phenomena such as supernovae, gamma-ray bursts, tidal disruption events where stars are torn apart by black holes, and gravitational wave counterparts all require immediate follow-up observations to capture their evolution.

Without a large-aperture telescope in the northern hemisphere, astronomers face severe limitations when responding to alerts from facilities like the upcoming Einstein Telescope. Gravitational wave events often have large positional uncertainties, requiring powerful telescopes to search wide areas of sky and identify the faint optical counterparts. The TMT's combination of light-gathering power and advanced instrumentation would make it uniquely capable of conducting these searches efficiently.

Funding Challenges and International Collaboration

The financial landscape for the TMT project has experienced significant turbulence. In June of the previous year, the United States government withdrew its funding support, creating a substantial budgetary shortfall that threatened the project's viability. This decision reflected both fiscal constraints and ongoing sensitivities surrounding the Mauna Kea controversy, with some American policymakers reluctant to support a project that had generated such significant opposition.

However, demonstrating the international nature of modern astronomical research, the Spanish government stepped forward to fill the funding gap left by the U.S. withdrawal. This commitment reflects Spain's recognition of the scientific prestige and technological benefits that hosting such a facility would bring. The Spanish investment also strengthens Europe's position in ground-based astronomy, complementing the European Southern Observatory's existing facilities in Chile.

The TMT partnership now includes institutions from Canada, Japan, China, and India, along with Spain's new commitment. This diverse international collaboration brings together complementary expertise in telescope engineering, instrumentation development, and observational astronomy. The project's total estimated cost exceeds $2.4 billion, making it one of the most ambitious ground-based astronomy projects ever undertaken.

Looking Toward the 2030s and Beyond

The TMT project team has formally moved on from the Mauna Kea site, focusing all planning efforts on La Palma. The target timeline aims to have the telescope operational by the late 2030s, coinciding with the expected commissioning of next-generation gravitational wave detectors. This synchronization is crucial—having the TMT online when these detectors begin operations will maximize the scientific return from both facilities.

Construction of a 30-meter class telescope represents an enormous undertaking, requiring years of careful site preparation, infrastructure development, and precision engineering. The telescope's segmented mirror must be manufactured to extraordinary tolerances, with each hexagonal segment polished to within nanometers of its target shape. The telescope's mounting and enclosure must be engineered to minimize vibrations while allowing rapid repositioning to track astronomical targets or respond to transient alerts.

Despite the absence of a final construction agreement with specific timelines, the project continues advancing through detailed design phases and site characterization studies at La Palma. The lack of local opposition—in stark contrast to the situation in Hawaii—removes a major obstacle that has plagued the project for years. The Canary Islands have a long history of hosting international astronomical facilities, and the local community generally views these observatories as sources of pride and economic benefit.

The Promise of Hemispheric Parity

When the TMT eventually sees first light from La Palma, it will restore balance to global astronomy, enabling northern hemisphere observations with capabilities matching those available in the south. Iconic targets like the Andromeda Galaxy—our nearest large galactic neighbor and a crucial laboratory for understanding galaxy evolution—will finally be observable with the resolution and sensitivity needed to resolve individual stars and star clusters across its full extent.

The telescope will also enable groundbreaking studies of exoplanetary atmospheres, using high-resolution spectroscopy to detect biosignature gases in the atmospheres of potentially habitable worlds orbiting nearby stars. Many of the most promising exoplanet targets lie in the northern sky, making the TMT essential for characterizing these distant worlds and searching for signs of life beyond Earth.

As humanity's observational capabilities continue expanding across the electromagnetic spectrum and into new domains like gravitational waves and neutrino astronomy, facilities like the TMT represent critical infrastructure for understanding our cosmic context. The journey from conception to construction has been long and challenging, marked by cultural conflicts, funding uncertainties, and technical complexities. Yet the scientific imperative remains clear: to fully understand the universe, we must be able to observe all of it with our most powerful instruments. The placement of the Thirty Meter Telescope at La Palma will help ensure that the northern sky receives the attention and scrutiny it deserves in the coming decades of astronomical discovery.