In a groundbreaking revelation about the early Universe, astronomers have uncovered compelling evidence that our cosmos experienced a mysterious warming period hundreds of millions of years before the first stars ignited. This discovery, published in two comprehensive studies in The Astrophysical Journal, challenges our understanding of the cosmic dark ages—that enigmatic billion-year period when the Universe existed in near-total darkness following the Big Bang. Using data from the Murchison Widefield Array in Western Australia, researchers have detected subtle signals indicating that intergalactic hydrogen began warming approximately 800 million years after the Universe's birth, raising profound questions about what energetic processes could have heated the cosmos during this supposedly dormant era.

The implications of this finding extend far beyond simple temperature measurements. By demonstrating that the Universe was thermally active during the dark ages, scientists must now reconsider the timeline and mechanisms of cosmic reionization—the process by which the Universe transformed from neutral to ionized as the first luminous objects formed. The research represents a decade-long effort to extract one of the faintest cosmological signals ever detected, pushing radio astronomy technology to its absolute limits.

From Cosmic Inferno to Transparent Darkness

To appreciate this discovery's significance, we must first understand the Universe's dramatic thermal evolution. The Big Bang initiated existence as an incomprehensibly hot, dense state where matter and energy existed in a roiling plasma. During these first moments, photons—the fundamental particles of light—could barely travel any distance before colliding with free electrons and ionized atomic nuclei. The Universe was opaque, like trying to see through an infinitely dense fog.

This chaotic state persisted for approximately 380,000 years until cosmic expansion cooled the Universe sufficiently for a critical transition: recombination. At this juncture, electrons finally combined with atomic nuclei to form stable neutral atoms, primarily hydrogen and helium. This transformation rendered the Universe optically transparent for the first time, allowing photons to stream freely through space. These ancient photons, stretched by 13.8 billion years of cosmic expansion, reach us today as the cosmic microwave background radiation—a faint microwave glow permeating all of space, discovered by Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson in 1965.

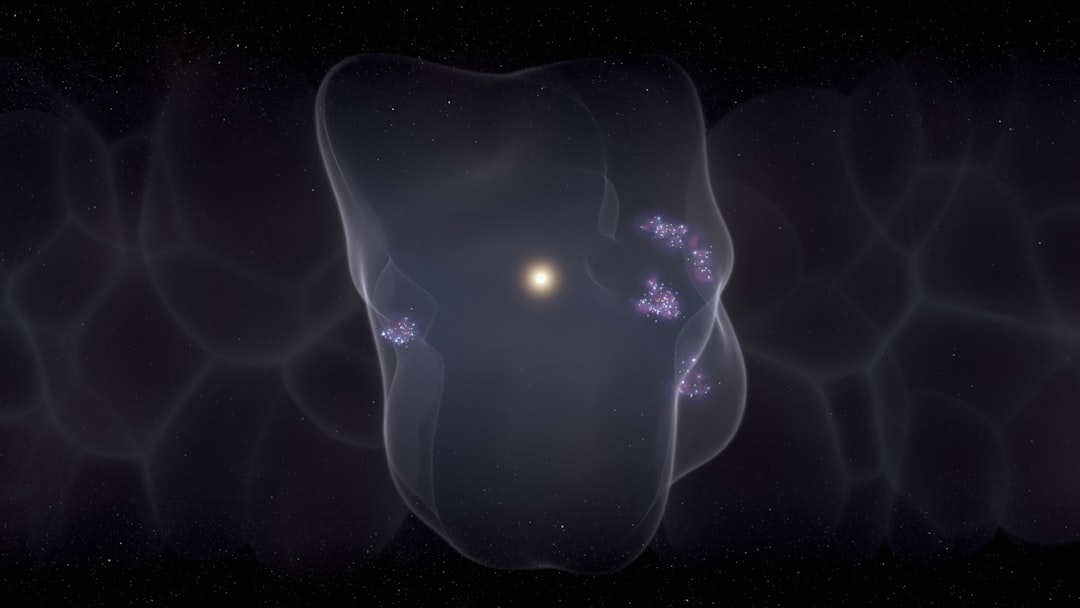

But transparency did not mean illumination. Following recombination, the Universe entered what cosmologists call the cosmic dark ages, a period lasting roughly one billion years. During this epoch, no stars existed to generate new light. The vast clouds of primordial hydrogen and helium continued cooling as the Universe expanded, their temperatures dropping toward absolute zero. Gravity worked slowly to pull matter together, but the first stars—which would eventually reignite the cosmos—had not yet formed. The Universe was transparent but profoundly dark, a cosmic void waiting for stellar ignition.

The Subtle Signal: Understanding the 21-Centimeter Line

While the cosmic dark ages lacked the brilliant light of stars and galaxies, the Universe wasn't entirely devoid of electromagnetic radiation. Neutral hydrogen atoms, which comprised the vast majority of cosmic matter, possessed a remarkable property: they could emit an extraordinarily faint radio signal known as the 21-centimeter line or hydrogen line.

This emission arises from a quantum mechanical phenomenon called hyperfine splitting. Both the proton in a hydrogen atom's nucleus and its orbiting electron possess a property called spin. When these spins align in the same direction, the atom exists in a slightly higher energy state than when they oppose each other. Occasionally—roughly once every ten million years for an isolated hydrogen atom—the electron spontaneously flips its spin orientation, dropping to the lower energy state and releasing the excess energy as a radio photon with a wavelength of precisely 21.106 centimeters.

This might seem like an impossibly faint signal, but hydrogen's overwhelming abundance throughout the Universe makes the 21-centimeter line one of the most important tools in radio astronomy. Since the 1950s, astronomers have used this emission to map the distribution of neutral hydrogen in our Milky Way galaxy and beyond. In fact, observations of the 21-centimeter line's Doppler shift—changes in wavelength caused by motion—provided the first compelling evidence for dark matter when astronomer Vera Rubin discovered that galaxies rotate far too rapidly to be held together by visible matter alone.

Observing the Epoch of Reionization

For studying the cosmic dark ages, astronomers focus specifically on the 21-centimeter emission during the Epoch of Reionization (EoR)—the transitional period when the first stars and galaxies began forming and their intense ultraviolet radiation started re-ionizing the neutral hydrogen that filled intergalactic space. This epoch, occurring roughly 150 million to one billion years after the Big Bang, represents one of the last major phase transitions in cosmic history.

However, detecting 21-centimeter signals from this ancient era presents extraordinary technical challenges. First, the signal is intrinsically faint—neutral hydrogen during the dark ages was cold and diffuse, producing minimal emission. Second, cosmic expansion has severely redshifted these signals, stretching their wavelength from 21 centimeters to several meters, placing them in a radio frequency range cluttered with terrestrial interference from FM radio, television broadcasts, and countless other human-generated signals. Extracting the cosmological signal from this cacophony is like hearing a whisper in a thunderstorm.

"The 21-centimeter signal from the Epoch of Reionization is approximately one million times fainter than the foreground contamination from our own galaxy and human-made radio interference. Detecting it requires not only sensitive instruments but also sophisticated data processing techniques that have taken decades to develop," explains Dr. Judd Bowman, a leading radio astronomer at Arizona State University working on similar observations.

A Decade of Data Reveals a Warm Universe

The two recent studies, led by researchers C.D. Nunhokee and Cathryn M. Trott, represent a monumental data analysis effort using observations from the Murchison Widefield Array (MWA) telescope. Located in the radio-quiet Australian outback, the MWA consists of 4,096 dipole antennas spread across approximately three kilometers, specifically designed to detect low-frequency radio emissions from the early Universe.

The research teams combined an entire decade's worth of MWA observations, accumulating thousands of hours of data to achieve the statistical sensitivity required to constrain the 21-centimeter power spectrum—a mathematical description of how the hydrogen signal varies across different spatial scales. This power spectrum contains encoded information about the temperature, density, and ionization state of hydrogen during the Epoch of Reionization.

Their analysis focused on redshifts between z=6.5 and z=7.0, corresponding to approximately 750-800 million years after the Big Bang. The results revealed something unexpected: the hydrogen gas was significantly warmer than predicted by "cold start" models of reionization. Rather than remaining at the frigid temperatures expected for gas that had been cooling for hundreds of millions of years, the intergalactic medium showed evidence of heating that began before the first stars became numerous enough to ionize their surroundings.

Key Findings from the Research

- Early Heating Detected: The 21-centimeter power spectrum measurements indicate that intergalactic hydrogen began warming approximately 800 million years after the Big Bang, earlier than previously thought possible through stellar processes alone.

- Ruling Out Cold Models: The data definitively excludes "cold start" scenarios for reionization, where hydrogen would have remained near its minimum temperature until stars suddenly ionized it. Instead, the Universe experienced gradual warming during the late dark ages.

- Improved Constraints: By utilizing advanced statistical techniques including Gaussian process modeling, the research achieved the most stringent limits yet on the 21-centimeter signal strength during this epoch, improving upon previous measurements by factors of several.

- Methodological Advances: The studies demonstrate that combining long-term observations with sophisticated foreground removal techniques can successfully extract cosmological signals despite overwhelming contamination, paving the way for future radio astronomy projects.

What Heated the Primordial Universe?

The discovery of pre-stellar warming presents cosmologists with an intriguing mystery: what energy source could have heated intergalactic hydrogen before stars became abundant? Several theoretical mechanisms have been proposed, each with profound implications for our understanding of the early Universe.

The leading hypothesis involves X-ray emission from primordial black holes and the earliest quasars. Even before the first massive stars formed, smaller "seed" black holes may have existed, perhaps formed from the direct collapse of dense gas clouds or as remnants of the very first generation of stars. As matter spiraled into these black holes, it would have heated to extreme temperatures, emitting copious X-rays. Unlike ultraviolet light, which is absorbed by neutral hydrogen, X-rays can penetrate deep into the intergalactic medium, depositing energy and gradually warming the gas across vast cosmic distances.

Alternative explanations include heating from dark matter annihilation or decay, exotic physics from the early Universe, or even more efficient energy transfer from the first stars than current models predict. The European Southern Observatory's Extremely Large Telescope, currently under construction, may help distinguish between these possibilities by detecting the earliest black holes and quasars directly.

Understanding this heating mechanism is crucial because it influenced how the first galaxies formed. Warmer gas is more resistant to gravitational collapse, potentially affecting the mass distribution of early galaxies and the efficiency of star formation. This, in turn, would have shaped the large-scale structure of the Universe we observe today.

Implications for Cosmology and Future Observations

These findings represent more than just a temperature measurement; they provide a crucial constraint on models of cosmic structure formation and the transition from the dark ages to the luminous Universe we inhabit. By establishing that the Universe was warm before it was bright, astronomers must now refine their models of how the first cosmic structures emerged from the primordial darkness.

The research also validates the observational strategy for next-generation radio telescopes. The Square Kilometre Array (SKA), currently under construction in South Africa and Australia, will be approximately 50 times more sensitive than the MWA. With such enhanced capabilities, the SKA should be able to not only detect the 21-centimeter signal with high confidence but also create detailed three-dimensional maps showing how reionization progressed across different regions of the Universe.

Additionally, these observations inform our understanding of the thermal history of the Universe more broadly. The temperature evolution of intergalactic gas serves as a cosmic thermometer, recording the energy injection from various astrophysical processes throughout cosmic history. By measuring this thermal history precisely, astronomers can constrain the properties of the first stars, the abundance of early black holes, and even test fundamental physics under extreme conditions impossible to recreate in laboratories.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite this progress, significant challenges remain. The current measurements provide upper limits and statistical constraints rather than direct detections of the 21-centimeter signal. Achieving an unambiguous detection will require even longer observation campaigns, improved calibration techniques, and potentially new approaches to separating the cosmological signal from foreground contamination.

Future research will focus on several key areas:

- Earlier Epochs: Pushing observations to higher redshifts (earlier times) to detect the moment when heating first began, potentially revealing its source.

- Spatial Variations: Moving beyond average measurements to map how heating varied across different regions, which would reveal the distribution of early energy sources.

- Multi-wavelength Coordination: Combining radio observations with infrared and X-ray telescopes to directly identify the objects responsible for heating the intergalactic medium.

- Theoretical Refinement: Developing more sophisticated models that incorporate the newly discovered warm phase to predict other observable consequences that can be tested.

A Universe Preparing for Light

The revelation that our Universe was warm before it was bright fundamentally alters our narrative of cosmic history. The cosmic dark ages, long imagined as a cold, dormant period of slow gravitational assembly, now appear far more dynamic. Even in the absence of starlight, energetic processes were actively reshaping the intergalactic medium, laying the thermal and chemical groundwork for the spectacular epoch of galaxy formation that would soon follow.

This research exemplifies the power of modern observational astronomy to peer into previously inaccessible epochs of cosmic history. By detecting signals billions of years old and millions of times fainter than foreground interference, astronomers are reconstructing the biography of our Universe with ever-increasing detail and precision.

As next-generation instruments come online and data analysis techniques continue advancing, we can expect even more surprises from the cosmic dark ages. Each discovery brings us closer to answering fundamental questions: How did the first stars form? What role did black holes play in shaping the early Universe? How did the cosmos transform from simple, nearly uniform conditions after the Big Bang into the rich tapestry of galaxies, stars, and planets we observe today?

The Universe's warm period before stellar ignition represents another chapter in this ongoing story of cosmic evolution—a reminder that even in darkness, the Universe was never truly dormant, but rather gathering its energy for the brilliant luminous era that would follow and ultimately give rise to worlds like our own.