For more than four centuries, scientists have grappled with a profound mystery that sits at the very heart of our understanding of reality: why does mathematics work so extraordinarily well in describing the physical universe? This question, which has puzzled physicists and philosophers alike, forms the foundation of what cosmologist Max Tegmark calls the mathematical universe hypothesis—a radical proposal suggesting that our universe isn't merely described by mathematics, but may actually be mathematics in its most fundamental form.

The story of this profound relationship between mathematics and physics begins with a simple but startling observation. Consider the improbability of a single tool—mathematics—being able to unlock virtually every mystery we've encountered in the natural world, from the microscopic realm of quantum particles to the vast expanses of cosmological structures. It's as if we discovered that one universal key could open every lock in existence, a coincidence so remarkable that it demands explanation.

This is the first installment in a comprehensive exploration of whether the universe is fundamentally mathematical in nature. Before we dive into the hypothesis itself, we must first understand the historical development of this "unreasonable effectiveness" of mathematics—a phrase coined by Nobel Prize-winning physicist Eugene Wigner in his landmark 1960 essay that would reshape how scientists think about the relationship between abstract mathematical concepts and physical reality.

The Miracle of Mathematical Effectiveness

In his groundbreaking essay published in the Communications in Pure and Applied Mathematics, Eugene Wigner articulated what many scientists had long felt but few had expressed so eloquently. He described the success of mathematics in physics as nothing short of miraculous, writing that "the miracle of the appropriateness of the language of mathematics for the formulation of the laws of physics is a wonderful gift which we neither understand nor deserve."

But what exactly did Wigner mean by "unreasonable effectiveness"? Consider that mathematics was developed largely through abstract reasoning, often without any regard for physical applications. Yet time and again, mathematical structures invented purely for their logical beauty or intellectual interest turn out to describe real phenomena in nature with stunning precision. Complex numbers, initially dismissed as mathematical curiosities, became essential to quantum mechanics. Non-Euclidean geometry, developed as an abstract exercise in the 19th century, proved indispensable to Einstein's general relativity.

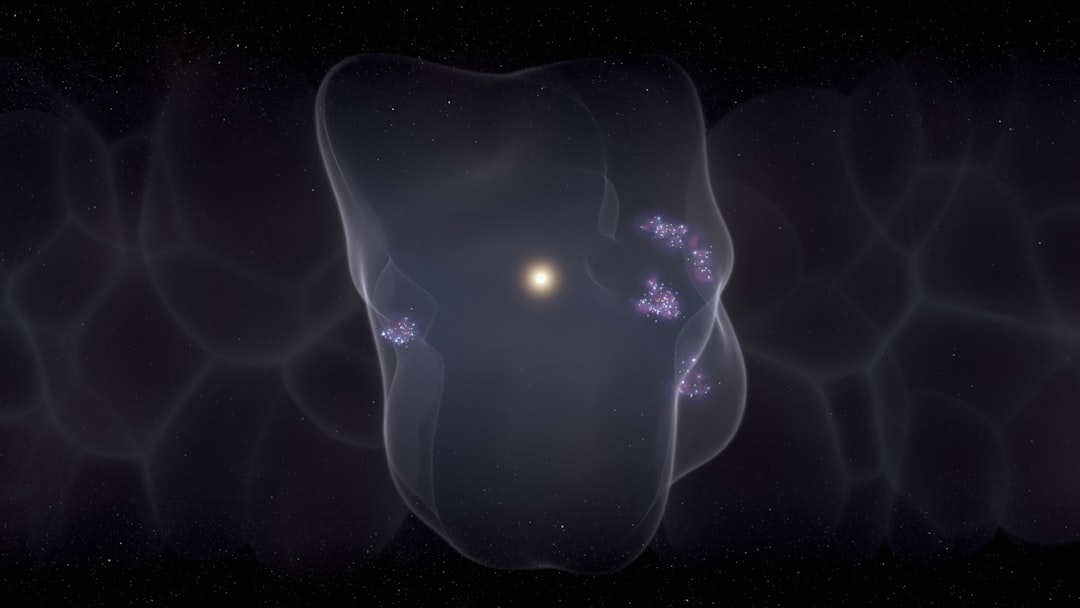

This pattern suggests something deeper than mere coincidence. As researchers at NASA's Hubble Space Telescope continue to probe the cosmos, they consistently find that the universe operates according to mathematical principles, from the precise orbital mechanics of exoplanets to the distribution of dark matter in galaxy clusters.

The Great Divide: Mathematics Versus Natural Philosophy

To appreciate the revolutionary nature of applying mathematics to physics, we must understand the intellectual landscape that existed before the Scientific Revolution. In the Western philosophical tradition stretching back to ancient Greece, mathematics and natural philosophy (what we now call physics) occupied entirely separate domains of knowledge.

Mathematics dealt with eternal, unchanging truths—the relationships between numbers, the properties of geometric figures, the harmonies of musical scales, and the predictable motions of celestial bodies. These were considered perfect and immutable aspects of reality. The Pythagorean theorem was true yesterday, is true today, and will be true tomorrow. The ratio of a circle's circumference to its diameter remains constant across all of space and time.

Natural philosophy, conversely, concerned itself with the messy, unpredictable world of change and transformation. How does a seed become a tree? Why does fire consume wood? What causes the tides? These processes seemed fundamentally different from the crystalline certainty of mathematical relationships. The idea that you could capture the growth of a living organism or the turbulent flow of water with equations seemed not just difficult, but conceptually misguided.

Galileo's Revolutionary Insight

Everything changed with Galileo Galilei in the early 17th century. While Galileo made numerous contributions to science—from his telescopic observations of Jupiter's moons to his experiments with falling bodies—perhaps his most transformative insight was methodological rather than empirical. Galileo proposed that the "book of nature" was written in the language of mathematics, and that understanding the physical world required learning to read this mathematical language.

"Philosophy is written in that great book which ever is before our eyes—I mean the universe—but we cannot understand it if we do not first learn the language and grasp the symbols in which it is written. The book is written in mathematical language, and the symbols are triangles, circles and other geometrical figures, without whose help it is impossible to comprehend a single word of it; without which one wanders in vain through a dark labyrinth."

This wasn't merely poetic language—it represented a fundamental reconceptualization of how scientific investigation should proceed. Galileo's approach was revolutionary and, importantly, controversial. Many natural philosophers of his era viewed his mathematical methods as inappropriate intrusions into their domain. How dare this mathematician presume to explain the workings of nature with mere numbers and equations?

But Galileo's methods produced results. His mathematical analysis of pendulum motion revealed patterns that had been literally swinging before humanity's eyes for millennia but had never been recognized. He discovered that the period of a pendulum's swing depends only on its length, not on the mass of the bob or the amplitude of the swing (for small angles). This insight, captured in simple mathematical relationships, led to revolutionary improvements in timekeeping and navigation.

The Cascade of Mathematical Discovery

Following Galileo's breakthrough, the floodgates opened. Johannes Kepler, working with Tycho Brahe's meticulous astronomical observations, discovered that planetary orbits weren't the perfect circles assumed since antiquity, but ellipses—a specific mathematical curve with precise geometric properties. This discovery, documented in ESA's historical archives, represented another triumph of mathematical description over qualitative observation.

But the true culmination of this mathematical revolution came with Isaac Newton. Faced with the challenge that mathematics seemed inherently static while physics dealt with change and motion, Newton didn't abandon the mathematical approach—he invented entirely new mathematics to handle it. His development of calculus (independently discovered by Gottfried Leibniz) provided the tools necessary to describe continuous change mathematically.

With calculus, Newton could write equations describing how velocities change over time (acceleration), how forces produce motion, and how gravitational attraction varies with distance. His Principia Mathematica, published in 1687, demonstrated that the same mathematical laws governing falling apples on Earth also controlled the motion of the Moon and planets—a unification of terrestrial and celestial physics that was nothing short of revolutionary.

The Modern Era: Mathematics Unleashed

The success of Newtonian mechanics established a template that physics has followed ever since. Modern physics is fundamentally a mathematical exploration of nature. Scientists search for patterns, symmetries, and relationships in natural phenomena, then express these discoveries as mathematical equations that can make precise, testable predictions.

This approach has led to discoveries that would have been literally unimaginable without mathematical guidance. Consider these examples:

- Electromagnetic Waves: James Clerk Maxwell's equations predicted the existence of electromagnetic waves traveling at the speed of light before anyone had detected radio waves experimentally. The mathematics pointed the way to an entire spectrum of radiation beyond visible light.

- Antimatter: Paul Dirac's mathematical treatment of quantum mechanics predicted the existence of antimatter—particles with the same mass but opposite charge as ordinary matter—years before positrons were discovered in cosmic ray experiments.

- Black Holes: Karl Schwarzschild's solution to Einstein's field equations predicted objects so dense that not even light could escape them, decades before observational evidence for black holes emerged. Today, facilities like LIGO detect gravitational waves from colliding black holes, confirming mathematical predictions made a century ago.

- The Higgs Boson: The mathematical structure of the Standard Model of particle physics required the existence of the Higgs field and its associated particle. Physicists spent billions of dollars building the Large Hadron Collider largely on the strength of this mathematical prediction, which was triumphantly confirmed in 2012.

In each case, mathematical reasoning led scientists to discoveries about physical reality. The mathematics wasn't just describing what we already knew—it was revealing aspects of nature that we hadn't yet observed, and in some cases couldn't have imagined without the mathematical framework.

The Deep Mystery: Why Does It Work?

This brings us back to Wigner's original puzzle, which remains as mysterious today as when he first articulated it. Why should abstract mathematical structures, developed through pure reasoning, correspond so precisely to the structure of physical reality? Why should equations scribbled on a blackboard tell us about the behavior of galaxies billions of light-years away, or particles too small to ever see directly?

Several possible explanations have been proposed. Perhaps mathematics is effective simply because we've defined it to be—we've constructed mathematical systems specifically to capture patterns we observe in nature. Or perhaps there's a selection bias at work: we notice and remember the cases where mathematics works spectacularly well, while forgetting the many instances where it fails or proves inadequate.

But these explanations seem insufficient given the depth and breadth of mathematics' success. The patterns we find aren't simple or obvious. They're often deeply hidden, revealed only through sophisticated mathematical analysis. And the same mathematical structures appear again and again in completely different physical contexts—the same differential equations describe heat flow, quantum mechanics, and financial markets.

This leads to a more radical possibility, one that we'll explore in greater depth in subsequent articles: perhaps mathematics is so effective at describing the universe because the universe is mathematics. Perhaps physical reality and mathematical structure aren't two different things that happen to correspond, but are actually identical. This is the essence of the mathematical universe hypothesis, and it raises profound questions about the nature of existence itself.

Looking Ahead: The Journey Continues

As we continue this series, we'll examine the mathematical universe hypothesis in detail, exploring both its compelling logic and its significant challenges. We'll consider what it would mean for the universe to be "made of math," how this idea relates to current physics and cosmology, and whether it can be tested scientifically. Research programs at institutions like the Institute for Advanced Study continue to explore these fundamental questions at the intersection of mathematics, physics, and philosophy.

For now, we're left with the remarkable fact that mathematics—this abstract creation of human thought—provides us with an extraordinarily powerful key for unlocking the secrets of nature. Whether this tells us something profound about the universe's fundamental nature, or something interesting about the human mind's ability to find patterns, remains an open and fascinating question. What's certain is that the relationship between mathematics and physical reality is far deeper and more mysterious than it might first appear, and exploring this relationship takes us to the very foundations of our understanding of existence itself.

The universe may be chaotic and complex, but beneath the apparent disorder lie patterns, symmetries, and relationships that mathematics captures with remarkable—some might say unreasonable—effectiveness. As we've seen, this effectiveness isn't a recent discovery but has been building for four centuries, transforming our understanding of reality at every step. The question now is whether we're ready to take the next conceptual leap: from mathematics as a description of reality to mathematics as reality itself.