In a remarkable achievement of astronomical detection, two independent research teams have simultaneously uncovered a super-Jupiter exoplanet orbiting a binary star system in data from the Gemini Planet Imager (GPI). This discovery, designated HD 143811 AB b, represents the closest directly imaged circumbinary planet ever found, orbiting its twin suns at a distance of just 60 astronomical units—approximately twice the distance from our Sun to Neptune. The finding, published in dual papers by teams from Northwestern University and the University of Exeter, challenges existing theories about planetary formation in complex stellar environments and provides unprecedented insights into how massive planets can exist in the gravitational dance of binary star systems.

What makes this discovery particularly intriguing is its timing and circumstances. Both research groups independently identified the planet while conducting comprehensive reviews of GPI's extensive dataset, which encompasses observations of more than 500 stellar systems. The catalyst for this simultaneous discovery appears to be the GPI's transition phase—the instrument recently completed its observational campaign at the Gemini South telescope in Chile and is currently being upgraded before deployment to Mauna Kea in Hawaii for northern hemisphere observations. This transitional moment prompted multiple teams to conduct thorough reanalysis of the accumulated data, leading to the serendipitous dual discovery of a world that had been hiding in plain sight within archival observations.

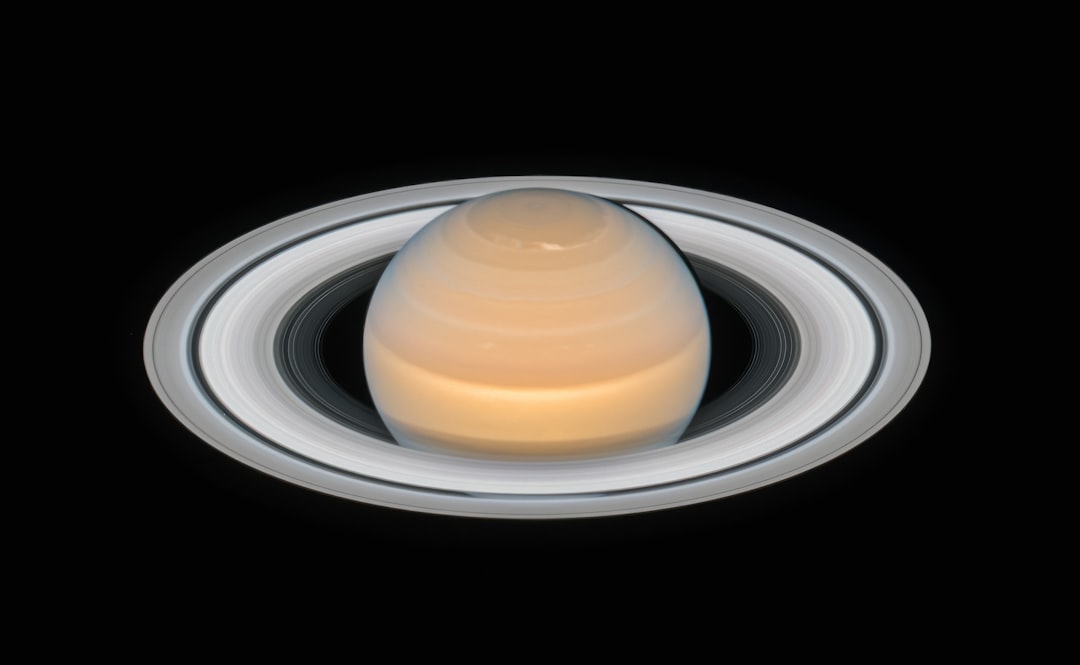

Breaking New Ground in Direct Exoplanet Imaging

The Gemini Planet Imager represents one of humanity's most sophisticated tools for directly observing planets beyond our solar system. Unlike the transit method or radial velocity techniques that detect planets indirectly through their effects on parent stars, direct imaging captures actual photons reflected or emitted by the planets themselves. This extraordinarily challenging technique requires advanced coronagraphs to block the overwhelming glare of host stars—a task comparable to spotting a firefly next to a lighthouse beam from hundreds of miles away.

Despite its technological prowess, GPI has successfully directly imaged only six exoplanets during its southern hemisphere campaign, including the two newly confirmed worlds from the recent data review. This modest number underscores the extreme difficulty of direct exoplanet detection, particularly for planets orbiting close to their parent stars. According to research published by the NASA Exoplanet Exploration program, fewer than 50 exoplanets have been directly imaged out of the more than 5,000 confirmed exoplanets discovered to date, highlighting just how exceptional each direct imaging success truly is.

Characteristics of an Extreme World

HD 143811 AB b defies easy categorization, possessing characteristics that place it at the intersection of multiple planetary classifications. With a mass approximately six times that of Jupiter, this world technically qualifies as a "super-Jupiter," though some scientists debate whether objects of this mass should be classified as planets or brown dwarfs—failed stars that never achieved sufficient mass to ignite hydrogen fusion in their cores. The planet's estimated surface temperature reaches a scorching 769 degrees Celsius (1,416 degrees Fahrenheit), heated by the intense radiation from its young binary star system.

The orbital dynamics of this system present fascinating complexities. While HD 143811 AB b maintains a relatively distant 60 AU orbit around its binary stars—which would place it well beyond Pluto in our own solar system—this distance is actually remarkably close for a circumbinary planet. The previous record holder for closest directly imaged circumbinary planet orbited at approximately 500 AU, nearly an order of magnitude farther out. Meanwhile, the two parent stars themselves orbit each other in a tight 18-day period, creating a complex gravitational environment that significantly influences the planet's formation history and current orbital stability.

"This planet formed when the dinosaurs were already extinct, about 13 million years ago—relatively recently in universe time," explained Dr. Jason Wang of Northwestern University, one of the study's lead authors. "Its discovery challenges our understanding of how quickly massive planets can form in circumbinary environments."

Location Within a Stellar Nursery

The HD 143811 system resides within the Scorpius-Centaurus (Sco-Cen) association, one of the nearest massive star-forming regions to Earth, located approximately 550 light-years away. This stellar nursery represents an ideal laboratory for studying planetary formation around young stars. The European Southern Observatory has extensively studied the Sco-Cen association, which contains hundreds of young stars still in the process of clearing their protoplanetary disks and establishing stable planetary systems.

The youth of the HD 143811 binary system—estimated at around 13 million years old—means these stars still emit significantly more energy than older, more stable stars like our Sun. This elevated luminosity contributes to the extreme temperatures observed on HD 143811 AB b and provides valuable data about how planetary atmospheres evolve in high-radiation environments during the early stages of system formation.

The Planetary Formation Puzzle

Perhaps the most scientifically intriguing aspect of HD 143811 AB b is the mystery surrounding its formation mechanism. Astronomers recognize two primary pathways for giant planet formation, each with distinct signatures and preferred environments. The discovery of this planet at such a relatively close orbital distance to its binary stars presents a theoretical conundrum that challenges both formation models.

Gravitational Instability Versus Core Accretion

The first formation mechanism, gravitational instability, occurs when regions within a protoplanetary disk become sufficiently dense to collapse directly into a planet-sized object. This process typically operates in the outer regions of planetary systems where the disk is cooler and denser, and it can form massive planets relatively quickly—on timescales of thousands rather than millions of years. Most previously imaged circumbinary planets, particularly those at large orbital distances, likely formed through this mechanism.

The alternative pathway, core accretion, represents the traditional model of planet formation. In this scenario, small solid particles in the protoplanetary disk gradually collide and stick together, forming progressively larger bodies. Once a solid core reaches approximately 10 Earth masses, it can begin rapidly accreting gas from the surrounding disk, potentially growing into a gas giant. Research from the Nature Astronomy journal suggests that core accretion typically requires millions of years and operates most efficiently in the inner regions of planetary systems.

HD 143811 AB b's intermediate orbital distance—too close for typical circumbinary gravitational instability formation, yet potentially too far for straightforward core accretion—suggests several possibilities. The planet may have formed through core accretion at an even closer orbital distance and subsequently migrated outward through gravitational interactions with the disk or the binary stars themselves. Alternatively, the unique dynamics of the binary system may have modified the conditions for gravitational instability, allowing it to operate at closer distances than typically expected.

Technological Innovation and Future Prospects

The successful detection of HD 143811 AB b demonstrates both the power and limitations of current direct imaging technology. The Gemini Planet Imager employs an advanced adaptive optics system coupled with a sophisticated coronagraph to suppress starlight and reveal faint planetary companions. The instrument can detect planets roughly one million times fainter than their host stars—an impressive feat, yet still insufficient to image planets in Earth-like orbits around Sun-like stars.

As GPI undergoes upgrades before its deployment to the northern hemisphere, engineers are implementing improvements to its coronagraph design that should enable detection of planets orbiting closer to their parent stars. The Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, scheduled for launch in the mid-2020s, will carry even more advanced coronagraph technology capable of directly imaging rocky planets in the habitable zones of nearby stars.

The Value of Archival Data Analysis

The discovery of HD 143811 AB b in archival data highlights an often-underappreciated aspect of modern astronomy: the immense scientific value locked within existing datasets. As data processing algorithms improve and as researchers develop new analysis techniques, old observations can yield fresh discoveries. This principle has proven particularly fruitful in exoplanet science, where subtle signals often require multiple analysis approaches to detect confidently.

The simultaneous independent discovery by two research teams also demonstrates the importance of reproducibility in science. When multiple groups using different analysis methods arrive at the same conclusion, it significantly strengthens confidence in the result. Both teams employed sophisticated image processing techniques to subtract starlight and reveal the faint planetary signal, but their independent confirmations eliminate concerns about systematic errors or analysis artifacts.

Implications for Planetary System Architecture

The existence of HD 143811 AB b has profound implications for our understanding of planetary system diversity. Binary and multiple star systems comprise approximately half of all stellar systems in our galaxy, meaning that understanding planetary formation and evolution in these complex environments is crucial for developing a complete picture of how planetary systems emerge and develop.

Previous theoretical work suggested that binary stars with tight orbital periods might prevent planet formation in their vicinity through gravitational perturbations that disrupt the protoplanetary disk. However, the growing census of circumbinary planets, including this newly discovered super-Jupiter, demonstrates that planets can indeed form and survive in these dynamically complex environments. Each new discovery refines our models and expands the parameter space where we know planets can exist.

Comparative Planetology

HD 143811 AB b provides an excellent opportunity for comparative planetology—the study of how planetary characteristics vary across different environments. Its extreme surface temperature, massive size, and unique orbital configuration make it an ideal target for atmospheric characterization studies. Future observations with instruments like the James Webb Space Telescope could potentially detect atmospheric components and study how the planet's atmosphere responds to the intense radiation environment created by its young binary stars.

The planet's 300-year orbital period, while extraordinarily long by human standards, offers scientists a chance to study how planetary atmospheres evolve over timescales relevant to climate change and atmospheric chemistry. Observations separated by even a few years could potentially detect seasonal changes or long-term atmospheric evolution driven by the planet's slowly changing distance from its binary stars.

Looking Toward Future Discoveries

As the Gemini Planet Imager prepares for its northern hemisphere campaign, astronomers anticipate discovering additional exoplanets in both new observations and archival data. The instrument's upgraded capabilities should enable detection of planets that were just below the sensitivity threshold of the original configuration, potentially doubling or tripling the number of directly imaged worlds.

The discovery of HD 143811 AB b also motivates continued development of next-generation direct imaging instruments. Projects like the Extremely Large Telescope's METIS instrument and space-based missions designed specifically for exoplanet direct imaging promise to revolutionize our ability to study planets around other stars. These future facilities may finally enable routine direct imaging of planets similar to those in our own solar system, including potentially habitable worlds orbiting Sun-like stars.

While HD 143811 AB b bears little resemblance to the fictional desert world of Tatooine—with its scorching temperatures, massive size, and centuries-long year—its discovery enriches our understanding of the incredible diversity of planetary systems in our galaxy. Each new world we discover expands our perspective on what is possible in the universe and brings us closer to answering the profound question of how common planets, and potentially life, truly are among the stars.