In a groundbreaking development that could finally illuminate one of cosmology's most perplexing enigmas, astrophysicists from the University of Amsterdam have unveiled a revolutionary method for detecting dark matter through the analysis of gravitational waves. This innovative approach, published in the prestigious journal Physical Review Letters, represents a significant leap forward in our quest to understand the invisible substance that comprises approximately 85% of the universe's matter content.

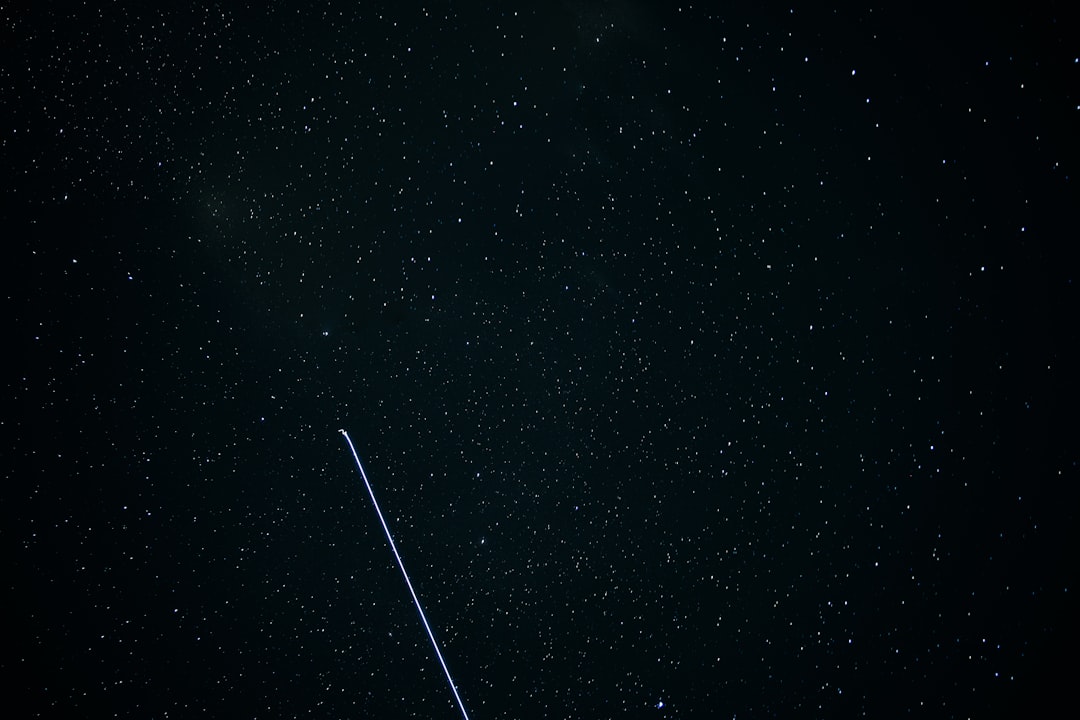

Nearly a decade has passed since the historic first detection of gravitational waves by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) in 2015, an achievement that validated Albert Einstein's century-old prediction and earned the Nobel Prize in Physics. Now, researchers are pushing the boundaries of what these ripples in spacetime can reveal, transforming gravitational wave astronomy from a tool for studying cosmic collisions into a potential dark matter detector of unprecedented sensitivity.

Bridging Two Frontiers of Modern Physics

The research team, led by Rodrigo Vicente, Theophanes K. Karydas, and Gianfranco Bertone from the University of Amsterdam's Institute of Physics and the GRAPPA centre of excellence (Gravitation and Astroparticle Physics Amsterdam), has developed the first fully relativistic framework for modeling how dark matter influences gravitational wave signals. This represents a dramatic departure from previous studies, which relied on simplified Newtonian approximations that couldn't capture the full complexity of these extreme cosmic environments.

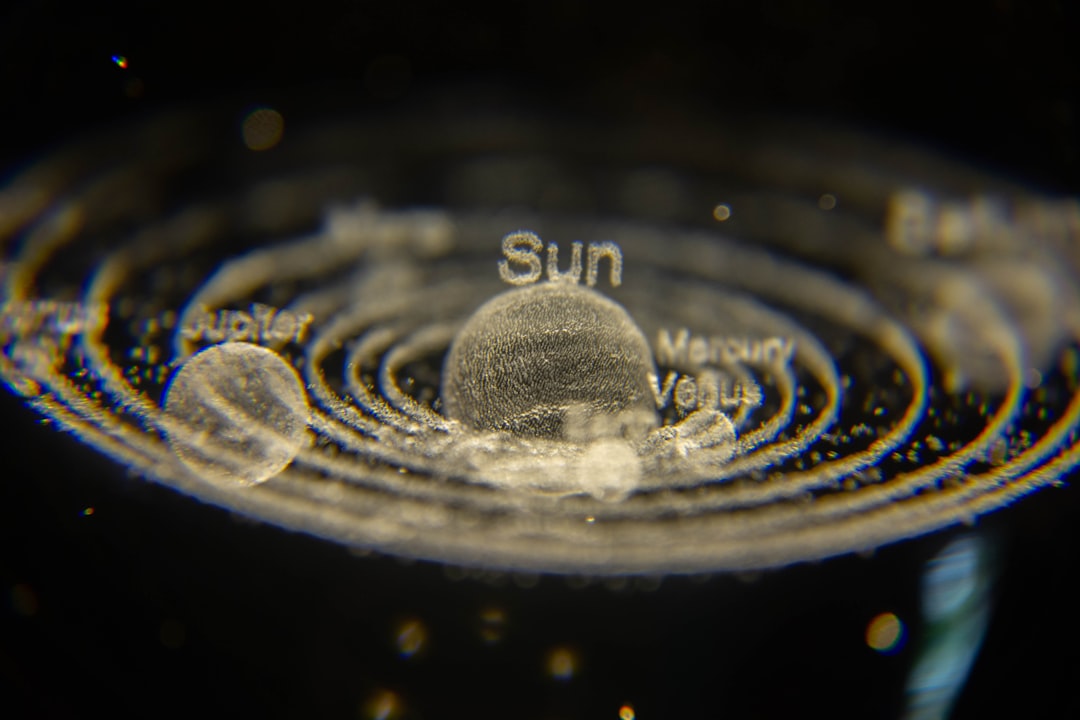

The key to their approach lies in understanding Extreme Mass-Ratio Inspirals (EMRIs)—dramatic cosmic events where smaller compact objects, such as stellar-mass black holes or neutron stars, spiral inexorably toward supermassive black holes millions of times more massive than our Sun. These death spirals can last for years, generating gravitational waves that encode detailed information about the environment through which they travel.

"By applying General Relativity rather than Newtonian gravity to describe how a black hole's environment affects an EMRI's orbit, we can now predict the subtle but distinctive signatures that dark matter would leave on gravitational wave signals," explains the research team in their groundbreaking paper.

The Dark Matter Enigma and Its Gravitational Signature

Dark matter remains one of the most vexing mysteries in modern cosmology. Despite constituting roughly 85% of all matter in the universe, this elusive substance has never been directly detected. Its existence is inferred only through its gravitational effects on visible matter, from the rotation curves of galaxies to the large-scale structure of the cosmos itself. Numerous experiments have attempted to detect dark matter particles directly, yet all have come up empty-handed, leading scientists to explore increasingly creative detection methods.

The Amsterdam team's research focuses on a particularly intriguing phenomenon: the formation of dark matter "spikes" or "halos" around supermassive black holes. Theoretical models suggest that dark matter should accumulate in extremely dense concentrations near these cosmic giants, creating distinctive structures that could reach densities billions of times higher than the average dark matter density in a galaxy. When an EMRI occurs in such an environment, the inspiraling object would plow through this dense dark matter, experiencing subtle but measurable effects on its trajectory.

How Dark Matter Leaves Its Fingerprint

The interaction between an inspiraling compact object and surrounding dark matter creates several observable effects on the resulting gravitational wave signal. The research team identified multiple mechanisms through which dark matter could leave its mark:

- Dynamical Friction: As the smaller object moves through the dark matter halo, it experiences a drag force that causes it to lose orbital energy more rapidly than it would in vacuum, accelerating the inspiral process and altering the gravitational wave frequency evolution.

- Gravitational Drag: The gravitational pull of the dark matter distribution itself can perturb the orbit, introducing characteristic deviations from the clean inspiral predicted in the absence of environmental effects.

- Accretion Effects: Dark matter particles falling into the inspiraling object could potentially add mass over time, though this effect is expected to be relatively minor compared to other mechanisms.

- Resonant Interactions: In certain configurations, the orbital frequency of the inspiraling object could resonate with characteristic frequencies in the dark matter distribution, amplifying the observable effects.

Next-Generation Gravitational Wave Observatories

The practical application of this research will come with the deployment of next-generation gravitational wave detectors, particularly the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA), scheduled for launch by the European Space Agency in the mid-2030s. Unlike ground-based detectors such as LIGO, which are sensitive to high-frequency gravitational waves from stellar-mass mergers, LISA will operate in space, free from terrestrial vibrations and capable of detecting the low-frequency waves produced by EMRIs and supermassive black hole mergers.

LISA's design is elegantly simple yet technologically demanding: three spacecraft flying in a triangular formation separated by 2.5 million kilometers will use laser interferometry to measure distance changes as small as a few picometers—less than the diameter of an atom. This extraordinary sensitivity will allow LISA to detect over 10,000 gravitational wave events during its mission lifetime, providing an unprecedented dataset for testing the dark matter detection methodology developed by the Amsterdam team.

Complementary Ground-Based Observations

While LISA represents the future of EMRI detection, current ground-based observatories continue to contribute valuable data. The Virgo Collaboration in Italy, LIGO's facilities in the United States, and the Kamioka Gravitational-wave Detector (KAGRA) in Japan form a global network that has already detected dozens of black hole and neutron star mergers. Although these stellar-mass events don't probe dark matter halos in the same way EMRIs do, they provide crucial calibration data and help refine our understanding of gravitational wave propagation through various cosmic environments.

Revolutionary Methodology and Computational Challenges

What sets this research apart is its commitment to using full General Relativistic calculations rather than approximations. Previous studies typically employed Newtonian gravity to model dark matter's effects on inspiraling objects—an approach that works reasonably well in weak gravitational fields but breaks down in the extreme environments near supermassive black holes, where spacetime itself is dramatically warped.

The team developed sophisticated computational models that combine state-of-the-art dark matter distribution profiles with precise gravitational wave templates. This required solving Einstein's field equations in highly complex geometries, a computational challenge that has only recently become tractable with modern supercomputers. Their models account for the relativistic motion of dark matter particles, the gravitational self-interaction of the dark matter halo, and the backreaction of the inspiraling object on its environment.

Implications for Dark Matter Physics

Successfully detecting dark matter through gravitational waves would represent a paradigm shift in our understanding of this mysterious substance. Current detection efforts focus primarily on two approaches: direct detection experiments that search for dark matter particles colliding with ordinary matter in ultra-sensitive detectors, and indirect detection through the products of dark matter annihilation or decay. Both approaches have yielded null results despite decades of increasingly sensitive searches.

Gravitational wave detection offers several unique advantages. First, it doesn't depend on the specific particle physics properties of dark matter—whether it consists of Weakly Interacting Massive Particles (WIMPs), axions, or some other exotic particle, its gravitational effects would still be detectable. Second, it probes dark matter in extreme environments where densities are far higher than anywhere in our galaxy, potentially amplifying subtle effects that would be undetectable elsewhere.

"This approach could finally provide direct evidence for dark matter's existence and reveal crucial information about its distribution and behavior in the most extreme gravitational environments in the universe," note the researchers in their conclusions.

Constraining Dark Matter Models

Beyond mere detection, gravitational wave observations could help discriminate between competing dark matter models. Different theoretical frameworks predict different dark matter density profiles around supermassive black holes. For instance, self-interacting dark matter models predict shallower density spikes than non-interacting models, while certain alternative theories like Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND) make no predictions about dark matter halos at all. By comparing observed gravitational wave signals with predictions from various models, scientists could narrow down the properties and nature of dark matter.

Looking Toward a New Era of Multi-Messenger Astronomy

This research exemplifies the growing field of multi-messenger astronomy, where scientists combine observations across different channels—electromagnetic radiation, gravitational waves, neutrinos, and cosmic rays—to build a comprehensive picture of cosmic phenomena. The Chandra X-ray Observatory, the James Webb Space Telescope, and future facilities will complement gravitational wave observations, potentially detecting electromagnetic signatures from the same events and providing additional context for interpreting the gravitational wave data.

The next decade promises to be transformative for gravitational wave astronomy. As LISA joins the observational arsenal and ground-based detectors undergo planned sensitivity upgrades, the volume of gravitational wave data will increase exponentially. Advanced machine learning algorithms are already being developed to sift through this data deluge, searching for the subtle signatures of dark matter that the Amsterdam team's research has shown should be detectable.

The convergence of theoretical predictions, computational modeling, and next-generation observational capabilities positions gravitational wave astronomy at the forefront of dark matter research. While many questions remain unanswered, this innovative approach offers genuine hope that one of cosmology's deepest mysteries may finally yield its secrets, written in the fabric of spacetime itself.