In a groundbreaking study that could finally solve one of planetary science's most perplexing mysteries, an international research team has developed a comprehensive framework explaining why Earth maintains active plate tectonics while its nearly identical twin, Venus, remains geologically stagnant. This research, published in Nature Communications, represents a paradigm shift in our understanding of how rocky planets evolve and what factors determine their capacity to support life as we know it.

The implications of this discovery extend far beyond our Solar System. By identifying six distinct tectonic regimes that govern planetary geological activity, scientists have created a powerful new tool for assessing the habitability potential of exoplanets orbiting distant stars. This framework bridges decades of fragmented theories about planetary evolution into a unified model that explains not only the stark differences between Earth and Venus, but also provides crucial insights into the geological histories of Mars, Mercury, and potentially habitable worlds beyond our cosmic neighborhood.

Led by Dr. Tianyang Lyu, a postdoctoral fellow at The University of Hong Kong, the research team employed sophisticated numerical modeling techniques to map out the complete spectrum of tectonic behaviors exhibited by terrestrial planets. Their work reveals that the path from geological death to vibrant tectonic activity is far more nuanced and predictable than previously imagined, with profound implications for understanding how and when Earth became capable of sustaining complex life.

The Fundamental Role of Plate Tectonics in Planetary Habitability

Plate tectonics represents far more than mere continental drift—it constitutes the very heartbeat of our living planet. This dynamic geological process functions as Earth's primary thermostat, regulating atmospheric composition and surface temperatures over geological timescales through an intricate feedback system known as the carbon-silicate cycle. Without this mechanism, Earth would likely have suffered the same fate as Venus, transforming into a hellish greenhouse world with surface temperatures exceeding 450°C (842°F).

The constant recycling of Earth's lithosphere—the rigid outer shell comprising the crust and uppermost mantle—serves multiple critical functions. At subduction zones, where oceanic plates dive beneath continental plates, carbon dioxide trapped in carbonate rocks is pulled deep into the mantle, effectively removing this potent greenhouse gas from the atmosphere. Conversely, volcanic activity at mid-ocean ridges and hotspots releases precisely calibrated amounts of CO₂ back into the atmosphere, maintaining the delicate balance necessary for liquid water to exist on the surface.

Furthermore, the churning of Earth's interior, driven by tectonic processes, sustains our planet's protective magnetic field. This invisible shield, generated by the geodynamo in Earth's liquid outer core, deflects harmful solar wind and cosmic radiation that would otherwise strip away our atmosphere and bombard the surface with lethal doses of high-energy particles. According to research from NASA's MAVEN mission, Mars lost most of its atmosphere precisely because its magnetic field collapsed billions of years ago when its interior cooled and geological activity ceased.

Decoding the Venus Paradox Through Advanced Computational Models

The enigma of Venus has haunted planetary scientists for decades. With a radius just 5% smaller than Earth's, a mass 81.5% that of our planet, and a similar bulk composition, Venus should theoretically exhibit comparable geological activity. Yet observations reveal a world frozen in geological time, its surface preserving impact craters and volcanic features that may be hundreds of millions of years old. Unlike the rapid cooling that silenced smaller worlds like Mars and Mercury, Venus's size should have allowed it to retain sufficient internal heat to drive plate tectonics.

Previous explanations for this paradox have proven unsatisfactory. Some researchers proposed that Venus's extremely hot surface temperature (hot enough to melt lead) might prevent the lithosphere from becoming sufficiently rigid to form distinct plates. Others suggested that the absence of water—which acts as a lubricant in Earth's subduction zones—might lock Venus's crust in place. However, these hypotheses failed to account for the full complexity of planetary tectonic evolution or explain the transitional states between different geological regimes.

Dr. Lyu and his colleagues approached this problem from an entirely new angle. Rather than focusing solely on present-day conditions, they conducted a comprehensive statistical analysis of thousands of mantle convection simulations, varying key parameters such as internal temperature, lithospheric strength, and compositional factors. This massive computational undertaking, which required processing power equivalent to millions of CPU hours, allowed them to map the complete landscape of possible tectonic behaviors for terrestrial planets.

"Through statistical analysis of vast amounts of model data, we were able to identify six tectonic regimes for the first time quantitatively. These include the mobile lid (like modern Earth), the stagnant lid (like Mars), and our newly discovered 'episodic-squishy lid.' This new regime is characterized by an alternation between two modes of activity, offering a fresh perspective on how planets transition from an inactive to an active state," explained Dr. Lyu in a statement released by the University of Hong Kong.

Six Tectonic Regimes: A Complete Framework for Planetary Evolution

The research team's analysis revealed that terrestrial planets can operate in one of six distinct tectonic regimes, each characterized by unique patterns of heat transfer, surface deformation, and magmatic activity. Understanding these regimes provides a Rosetta Stone for interpreting the geological histories recorded in planetary surfaces throughout our Solar System and beyond.

The Mobile Lid Regime: Earth's Dynamic State

The mobile lid regime represents the pinnacle of geological activity, characterized by multiple rigid plates that move independently across the planet's surface. This is the regime Earth currently occupies, featuring well-defined spreading centers at mid-ocean ridges, transform faults like California's San Andreas Fault, and subduction zones encircling the Pacific Ocean in the famous "Ring of Fire." In this state, heat from the planet's interior escapes efficiently through both the creation of new lithosphere at ridges and the recycling of old, cold lithosphere at subduction zones.

The Stagnant Lid Regime: Geological Death

At the opposite extreme lies the stagnant lid regime, exemplified by Mars and Mercury. In this state, the entire lithosphere forms a single, immobile shell that acts as an insulating blanket, trapping heat within the planetary interior. While some heat escapes through conduction and occasional volcanic eruptions at hotspots, the lack of plate recycling means these worlds gradually cool and become increasingly geologically inert. Research from ESA's Mars Express has confirmed that Mars transitioned to this regime over 3.5 billion years ago.

The Plutonic-Squishy Lid Regime: Venus's Current State

The plutonic-squishy lid regime represents a particularly intriguing intermediate state that may explain Venus's current geology. In this regime, rising plumes of hot magma from the deep mantle weaken the lithosphere from below, creating localized zones of deformation and volcanic activity without achieving the global-scale plate recycling characteristic of Earth. This produces a surface marked by extensive volcanic plains, pancake domes, and coronae—circular tectonic features unique to Venus—while lacking the linear mountain chains and deep ocean trenches that define plate boundaries on Earth.

The Episodic-Squishy Lid Regime: A New Discovery

Perhaps the most revolutionary finding was the identification of the episodic-squishy lid regime, a previously unrecognized state characterized by alternating periods of relative quiescence and intense geological activity. In this regime, heat gradually builds up beneath the stagnant lithosphere until pressure becomes sufficient to trigger catastrophic resurfacing events, where large portions of the planetary surface melt, overturn, and reform over geologically brief timescales (tens of millions of years). Evidence suggests Venus may have experienced such an event approximately 500 million years ago, potentially explaining why its surface appears relatively young despite the planet's 4.5-billion-year age.

Sluggish Lid and Transitional Regimes

The remaining regimes—sluggish lid and various transitional states—represent intermediate behaviors where the lithosphere exhibits limited mobility, with plates moving extremely slowly or episodically. These regimes may characterize early Earth during the Archean Eon (4 to 2.5 billion years ago), before full-fledged plate tectonics emerged, and could be common on super-Earths—rocky exoplanets more massive than Earth but smaller than Neptune.

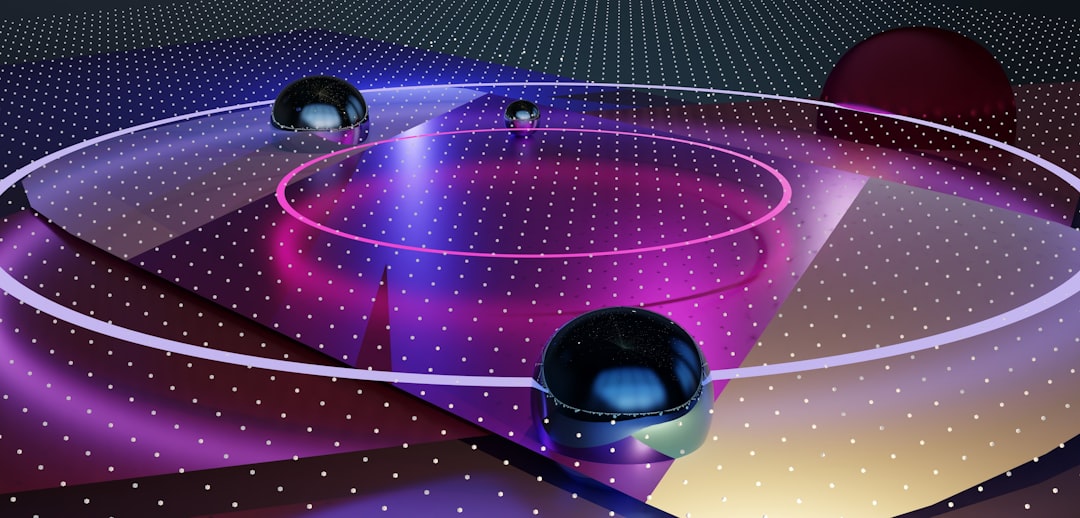

Hysteresis and the Memory of Planets: Why History Matters

One of the most sophisticated aspects of this research involves accounting for hysteresis—the phenomenon where a system's current state depends not only on present conditions but also on its historical path. In planetary geology, this means that two planets with identical present-day properties (mass, composition, internal temperature) could exhibit completely different tectonic behaviors based on their evolutionary histories.

The research team developed a comprehensive tectonic transition diagram that maps how planets move between different regimes as they cool over billions of years. This diagram reveals that certain transitions are highly probable while others are virtually impossible without external intervention. For instance, a planet in the stagnant lid regime rarely spontaneously transitions to mobile lid tectonics—the lithosphere must first weaken through processes such as water infiltration, compositional changes, or impacts from large asteroids.

This finding provides crucial context for understanding Earth's geological history. Evidence from ancient rocks suggests that Earth's lithosphere has progressively weakened over time, becoming more susceptible to fracturing and plate formation. This weakening may have resulted from the gradual cooling of the mantle, changes in crustal composition due to the emergence of continents, or the influence of water cycling through subduction zones. The transition to full plate tectonics likely occurred sometime between 3 and 2 billion years ago, coinciding with the rise of atmospheric oxygen and the emergence of complex life—likely not a coincidence.

Implications for the Search for Habitable Worlds

The practical applications of this research extend far beyond understanding our Solar System's planets. As astronomers discover thousands of rocky exoplanets in the habitable zones of distant stars, the question of which worlds might support life becomes increasingly urgent. This new tectonic framework provides testable predictions about which planets are most likely to maintain the geological activity necessary for long-term habitability.

According to the models, planets slightly larger than Earth (1.5 to 2 Earth masses) may be optimal for sustaining plate tectonics over billions of years. These super-Earths possess greater internal heat reserves and stronger gravitational fields, both of which promote vigorous mantle convection and efficient heat loss through tectonic recycling. Conversely, planets significantly smaller than Earth (less than 0.5 Earth masses) likely cool too rapidly to maintain long-term geological activity, while planets much larger may develop such thick lithospheres that plate tectonics becomes impossible.

Professor Maxim D. Ballmer from University College London, a co-author of the study, emphasized the broader significance of their findings:

"Our models intimately link mantle convection with magmatic activity. This allows us to view the long geological history of Earth and the current state of Venus within a unified theoretical framework, and it provides a crucial theoretical basis for the search for potentially habitable Earth analogs and super-Earths outside our solar system."

Resolving the Venus Volcanism Debate

This research arrives at a particularly opportune moment in Venus studies. For decades, planetary scientists debated whether Venus remains volcanically active or has been geologically dead for hundreds of millions of years. Recent observations from ESA's Venus Express and reanalysis of data from NASA's Magellan mission have provided tantalizing hints of ongoing volcanic activity, including apparent changes in sulfur dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere and possible lava flows less than a few million years old.

The new tectonic framework strongly supports the hypothesis of continued Venusian volcanism while explaining why this activity differs fundamentally from Earth's tectonics-driven volcanism. In the plutonic-squishy or episodic-squishy lid regimes identified for Venus, volcanic activity results from mantle plumes rising independently rather than from plate boundary processes. This produces the scattered, localized volcanic features observed on Venus rather than the linear volcanic chains (like Hawaii or Iceland) or arc volcanism (like the Andes or Cascades) seen on Earth.

This insight provides crucial guidance for upcoming Venus missions, including NASA's DAVINCI and VERITAS missions, as well as ESA's EnVision orbiter, all scheduled to launch later this decade. The research team's models identify specific regions where volcanic activity is most likely to occur, allowing mission planners to target these areas for detailed observation and potentially catch Venus in the act of erupting.

Future Directions and Unanswered Questions

While this research represents a major leap forward, numerous questions remain about the factors controlling planetary tectonic evolution. The role of water deserves particular attention—Earth's oceans not only moderate surface temperature but also profoundly influence mantle rheology (flow properties) and lithospheric strength. The exact amount of water necessary to trigger and sustain plate tectonics remains uncertain, with implications for assessing the habitability of ocean worlds like Jupiter's moon Europa or Saturn's Enceladus.

Additionally, the influence of planetary rotation rate, tidal heating from nearby bodies, and the presence of large moons (which may stabilize planetary obliquity and climate) all warrant further investigation. Future research will undoubtedly refine these models by incorporating these additional factors, potentially revealing even more nuanced relationships between planetary properties and tectonic behavior.

The research team's comprehensive framework also opens new avenues for laboratory experiments. By recreating the extreme pressures and temperatures of planetary interiors in specialized facilities, scientists can test the model's predictions about how different rock compositions and water contents affect lithospheric behavior. Such experiments, combined with continued analysis of meteorites and samples from other Solar System bodies, will help validate and refine the theoretical framework.

A Unified Theory of Terrestrial Planet Evolution

Perhaps the most profound contribution of this research lies in its unification of previously disparate observations and theories into a single, coherent framework. For the first time, scientists can place Earth, Venus, Mars, and Mercury along a continuum of tectonic evolution, understanding each world not as an isolated case but as one example drawn from a broader spectrum of possibilities governed by fundamental physical principles.

This unified perspective transforms our understanding of planetary habitability from a binary question—"Does this planet have plate tectonics or not?"—into a more nuanced assessment of where a world sits within the tectonic regime landscape and how it might evolve over time. As Dr. Lyu and his colleagues continue to refine their models and apply them to newly discovered exoplanets, we move closer to answering one of humanity's most ancient questions: Are we alone in the universe, or does life flourish on other worlds blessed with the geological dynamism that has sustained Earth's biosphere for billions of years?

The answer to that question may ultimately depend on understanding the subtle factors that determine whether a rocky planet develops the active, mobile lid tectonics that have made Earth a haven for life—or remains frozen in one of the geologically inactive states that characterize our planetary neighbors. This research provides the theoretical foundation necessary to make that determination, marking a pivotal moment in our quest to understand our place in the cosmos.