The tantalizing prospect of discovering subsurface liquid water on Mars has taken a significant blow, as new high-resolution radar observations from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) cast serious doubt on the existence of a purported underground lake near the Martian south pole. The findings, recently published in Geophysical Research Letters by a team led by Dr. Gareth Morgan from the Planetary Science Institute, represent a major setback for those hoping that Mars might harbor accessible liquid water reservoirs beneath its icy polar caps.

The controversy dates back to 2018, when researchers analyzing data from the MARSIS (Mars Advanced Radar for Subsurface and Ionosphere Sounding) instrument aboard the European Space Agency's Mars Express orbiter announced they had detected what appeared to be a bright radar reflection beneath the south polar ice cap. This signal, they argued, was most consistent with the presence of briny liquid water—a discovery that would have profound implications for Martian habitability and future exploration missions. The announcement sparked intense scientific debate and captured public imagination, raising questions about whether Mars might still harbor environments capable of supporting microbial life.

However, the latest observations utilizing MRO's enhanced capabilities tell a dramatically different story, one that highlights both the challenges of remote planetary exploration and the importance of multi-instrument verification in scientific discovery.

The Original Discovery and Its Significance

When the MARSIS team first reported their findings in 2018, the implications seemed revolutionary. Operating at relatively low radar frequencies between 1.8 and 5 MHz, MARSIS detected an unusually reflective region approximately 20 kilometers wide beneath the layered ice deposits at Mars' south pole. The radar return from this subsurface feature was significantly brighter than the reflection from the ice surface itself—a characteristic typically associated with the presence of liquid water, which has distinctive electromagnetic properties that make it highly reflective to radar waves.

The discovery was particularly intriguing because it suggested that despite Mars' frigid surface temperatures, which average around -63°C (-81°F), liquid water could persist in subsurface environments. Scientists theorized that high concentrations of dissolved salts—primarily perchlorates, which are abundant on Mars—could dramatically lower the freezing point of water, potentially allowing it to remain liquid even at temperatures well below 0°C. This phenomenon, known as freezing point depression, is well-documented on Earth in environments ranging from Antarctic subglacial lakes to deep ocean brine pools.

Technical Challenges and the SHARAD Conundrum

From the outset, the MARSIS findings faced scrutiny partly because another radar instrument, SHARAD (Shallow Radar) aboard MRO, had been unable to confirm the detection. SHARAD operates at significantly higher frequencies, between 15 and 25 MHz, which provides superior spatial resolution but comes with a critical trade-off: reduced penetration depth, especially through materials like water ice that can absorb electromagnetic radiation.

For years, mission scientists attributed SHARAD's inability to detect the purported lake to these inherent technical limitations. However, this explanation became less satisfying as researchers developed a more sophisticated understanding of how radar signals interact with Martian subsurface materials. The scientific literature began to fill with alternative hypotheses that could explain the MARSIS observations without invoking liquid water.

The breakthrough came from an unexpected source: a risky operational maneuver that would fundamentally enhance SHARAD's capabilities and provide the definitive data needed to resolve the controversy.

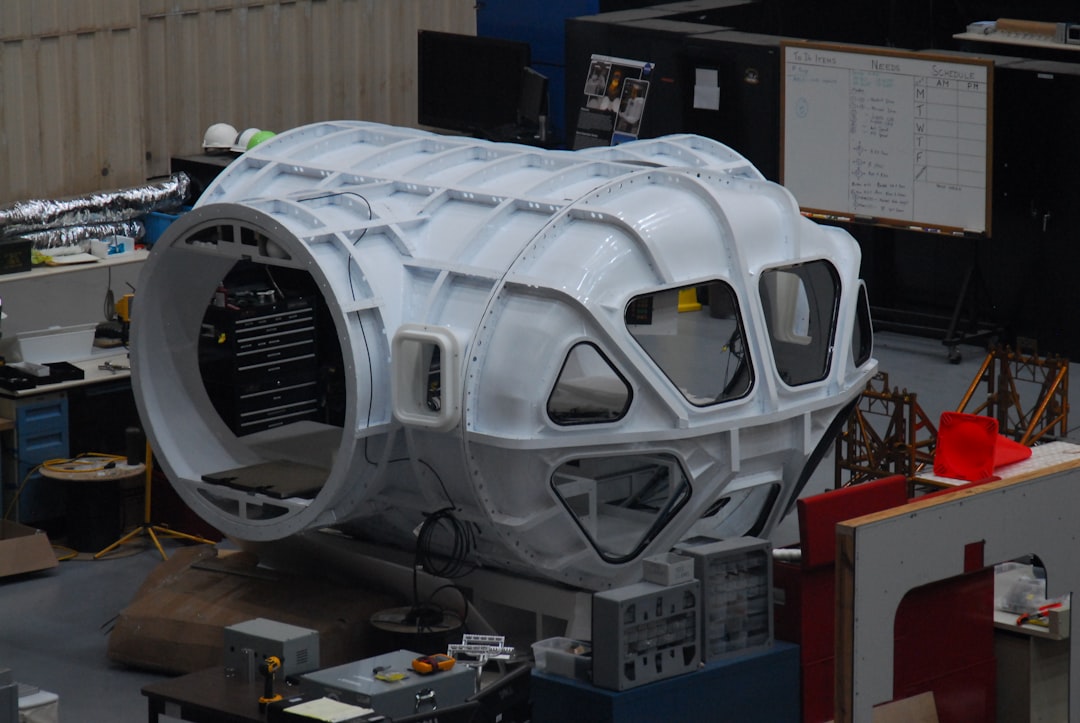

The Very Large Roll Maneuver: A Game-Changing Innovation

Throughout most of its operational life, MRO's SHARAD instrument faced a significant handicap. The radar antenna was mounted on the "back" of the spacecraft, meaning that the orbiter's metallic body sat between the antenna and the Martian surface during normal operations. This configuration resulted in signal attenuation of up to 10 decibels—a substantial reduction that severely limited the instrument's ability to probe deep subsurface structures. In the logarithmic scale of electromagnetic power, a 10 dB loss represents a tenfold reduction in signal strength, dramatically compromising the radar's effectiveness.

Engineers had long understood this limitation but considered the solution too risky to implement during MRO's primary mission phase. The answer lay in performing what mission controllers termed a "Very Large Roll" (VLR)—rotating the entire spacecraft 120 degrees on its axis to point SHARAD directly at the Martian surface. This maneuver would eliminate the interference from the spacecraft body but required precise control and carried risks of disrupting the orbiter's carefully calibrated systems.

"After nearly two decades of faithful service, we determined that MRO had earned the right to take some calculated risks," explained mission engineers. "The potential scientific payoff from improved SHARAD data justified attempting these challenging maneuvers during the extended mission phase."

The first successful VLR was executed in June, and the results exceeded expectations. SHARAD's enhanced signal strength allowed it to probe up to 1.5 kilometers deeper into the south polar ice deposits than ever before, providing unprecedented clarity in subsurface imaging.

The Verdict: No Lake Detected

When SHARAD's newly enhanced capabilities were directed toward the location of the purported subsurface lake, the results were unambiguous—and disappointing for those hoping to confirm the presence of liquid water. Despite its improved penetration depth and signal clarity, SHARAD detected no bright subsurface reflection at the site where MARSIS had observed its anomalous signal.

The quantitative analysis was particularly telling. While the 2018 MARSIS data had shown a subsurface reflection significantly brighter than the surface return—a key indicator supposedly pointing to liquid water—SHARAD found only a reflection approximately 0.1% as strong as the surface signal. This dramatic discrepancy demanded explanation, and the research team pursued two primary hypotheses to account for the divergent observations.

Investigating the Signal Attenuation Hypothesis

The first possibility considered by Dr. Morgan's team was that the south polar ice might possess unusual properties that selectively absorbed SHARAD's higher-frequency signals while allowing MARSIS's lower frequencies to penetrate and reflect. This scenario would mean that liquid water could still exist at depth, but SHARAD simply couldn't detect it due to signal loss in the overlying ice.

To test this hypothesis, researchers conducted detailed analyses of radar signal attenuation patterns across the south polar region. They compared signal loss at the purported lake location with that observed in nearby areas with similar ice thickness and composition. The results were definitive: no unusual attenuation patterns were detected that could account for SHARAD's inability to see a liquid water reservoir. The ice in the region appeared electromagnetically transparent enough that SHARAD should have easily detected any significant liquid water body if one existed.

The Dry Rock Alternative: A More Plausible Explanation

The second hypothesis—and the one that the research team found most compelling—proposes that the MARSIS signal originated not from liquid water but from unusually smooth, dry rock formations, possibly ancient crater floors filled with fine-grained sediment. Such geological features could act as effective radar reflectors at MARSIS's lower frequencies, creating a mirror-like return that might be mistaken for liquid water.

This interpretation aligns with our understanding of how different radar frequencies interact with planetary surfaces. Lower-frequency radar waves, like those used by MARSIS, are more sensitive to large-scale surface roughness and can produce strong reflections from smooth geological contacts. Higher-frequency systems like SHARAD, while offering better resolution, are less likely to generate such pronounced reflections from the same features.

The dry rock hypothesis also resolves several puzzling aspects of the original lake claim that had troubled planetary scientists. For liquid water to exist at the depths and temperatures inferred from the MARSIS data, either extraordinary geothermal heating or implausibly high salt concentrations would be required—conditions that seem inconsistent with our broader understanding of Martian geology and climate history.

Previous Skepticism and Supporting Evidence

The new SHARAD findings are not the first evidence casting doubt on the subsurface lake hypothesis. Since the original 2018 announcement, multiple research groups have proposed alternative explanations for the MARSIS observations, each highlighting different physical or geological mechanisms that could produce similar radar signatures without requiring liquid water.

One particularly influential study demonstrated that frozen clay minerals—which do contain water molecules locked within their crystalline structure but are not liquid—can generate radar reflections bright enough to mimic the MARSIS signal. Clay minerals are abundant on Mars and are known to exist in the polar regions, making this a geologically plausible alternative. The water in these minerals is chemically bound and inaccessible to potential life forms, making such deposits far less exciting from an astrobiological perspective than a liquid water reservoir.

Other researchers pointed out the thermodynamic challenges inherent in the liquid water interpretation. Calculations showed that maintaining liquid water at the observed depth would require either geothermal heat flow several times higher than expected for Mars' ancient, geologically inactive crust, or brine solutions with salt concentrations approaching saturation—so salty that they would likely be inhospitable to any known form of life. According to NASA's Mars exploration program, neither scenario fits well with other observations of the Martian south polar region.

Implications for Mars Exploration and Future Missions

While the apparent absence of a subsurface lake may disappoint those hoping for easily accessible water resources on Mars, the enhanced capabilities demonstrated by MRO's Very Large Roll maneuvers open exciting new avenues for planetary exploration. Mission scientists are now planning to use SHARAD's improved performance to search for subsurface ice deposits near the Martian equator—a discovery that would have profound implications for future human exploration.

Equatorial ice would be vastly more accessible than polar deposits for several reasons. The warmer temperatures at lower latitudes would make surface operations easier and less energy-intensive. Additionally, equatorial regions receive more consistent sunlight for solar power generation and experience less extreme seasonal variations. If substantial ice deposits exist at accessible depths near the equator, they could provide crucial resources for in-situ resource utilization (ISRU)—the practice of using local materials to support human missions rather than transporting everything from Earth.

The search for equatorial ice is not merely speculative. Various lines of evidence, including neutron spectrometer data and observations of recent impact craters, suggest that water ice may indeed lurk beneath the surface at surprisingly low latitudes. SHARAD's enhanced capabilities could definitively map these deposits, providing essential data for mission planning by organizations like SpaceX and international space agencies developing Mars exploration architectures.

Lessons in Scientific Methodology and Verification

The saga of the Martian subsurface lake offers valuable lessons about the scientific process, particularly in the challenging realm of remote planetary exploration. The initial MARSIS detection was based on legitimate observations interpreted through the lens of established scientific principles. However, as this case demonstrates, extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence—and preferably verification through multiple independent measurement techniques.

The resolution of this controversy also highlights the importance of technological innovation in planetary science. The Very Large Roll maneuver, initially deemed too risky to attempt, ultimately provided the critical data needed to resolve a major scientific debate. This willingness to take calculated risks with aging spacecraft during extended mission phases has become an increasingly important strategy for maximizing scientific return from planetary missions.

- Multi-instrument verification: The importance of confirming significant discoveries using multiple independent measurement techniques with different sensitivities and limitations

- Technological adaptation: How innovative operational procedures can dramatically enhance the capabilities of long-serving spacecraft, extending their scientific productivity

- Alternative hypotheses: The necessity of thoroughly exploring all plausible explanations for anomalous observations before accepting extraordinary interpretations

- Thermodynamic constraints: The value of applying fundamental physical principles to evaluate the plausibility of proposed phenomena

The Continuing Search for Martian Water

Despite this setback, the search for accessible water on Mars continues with undiminished intensity. Water remains the most critical resource for future human exploration and the most promising indicator of potential past or present life. While a large subsurface lake would have been a spectacular discovery, Mars harbors water in many other forms—from the obvious polar ice caps to hydrated minerals scattered across the surface, from seasonal frost deposits to possible deep groundwater reservoirs yet to be discovered.

Recent missions, including the Perseverance rover currently exploring Jezero Crater, continue to investigate Mars' complex hydrological history. Evidence suggests that ancient Mars possessed a much wetter climate, with rivers, lakes, and possibly even oceans covering portions of its surface. Understanding where that water went—whether lost to space, locked in polar ice, or sequestered in subsurface reservoirs—remains one of the central questions driving Mars exploration.

As MRO enters its third decade of operation, having far exceeded its original two-year mission timeline, it continues to demonstrate that even veteran spacecraft can make crucial contributions to our understanding of Mars. The enhanced SHARAD capabilities achieved through the Very Large Roll maneuvers ensure that this resilient orbiter will continue producing valuable science for years to come, perhaps even detecting the first confirmed equatorial ice deposits that future Mars explorers will depend upon for survival.

The story of the Martian subsurface lake—from exciting discovery to skeptical scrutiny to apparent refutation—exemplifies the self-correcting nature of science at its best. While the absence of easily accessible liquid water near the south pole may disappoint some, the rigorous process that led to this conclusion strengthens our confidence in future discoveries and demonstrates the remarkable capabilities of our robotic explorers orbiting the Red Planet.