A quarter-century of groundbreaking astronomical observations has culminated in a breathtaking new portrait of one of the cosmos' most spectacular stellar remnants. The Gemini South Observatory, perched high in the Chilean Andes at 2,737 meters elevation, has captured a stunning image of NGC 6302—more commonly known as the Butterfly Nebula—to commemorate 25 years of scientific excellence. This celestial wonder, located approximately 3,000 light-years from Earth in the constellation Scorpius, represents not just a beautiful cosmic photograph, but a profound glimpse into the violent and spectacular death throes of a massive star.

The selection of this particular target wasn't made by veteran astronomers or observatory directors, but rather by Chilean students who participated in the Gemini First Light Anniversary Image Contest. Given the choice between observing a star-forming nebula, supernova-remnant" class="glossary-term-link" title="Learn more about Supernova Remnant">supernova remnant, star cluster, planetary nebula, or galaxy, the students overwhelmingly chose the Butterfly Nebula—a decision that speaks to humanity's enduring fascination with these colorful cosmic clouds. Their choice highlights how planetary nebulae, despite their misleading name that dates back to early telescopic observers, continue to captivate both professional astronomers and the public alike with their intricate structures and vibrant displays of ionized gases.

The Architecture of Stellar Death: Understanding Bipolar Planetary Nebulae

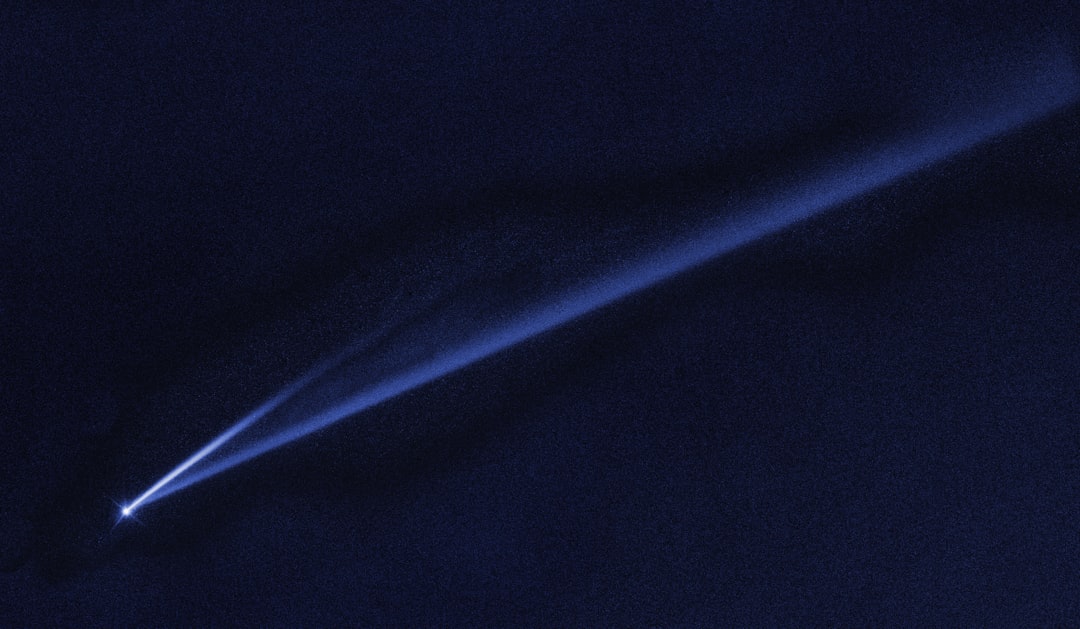

The Butterfly Nebula exemplifies what astronomers classify as a bipolar planetary nebula, characterized by two distinct lobes of expelled stellar material extending in opposite directions from a central white dwarf star. This distinctive morphology, which gives NGC 6302 its butterfly-like appearance, results from complex physical processes that occur during the final stages of stellar evolution. The NASA Hubble Space Telescope has extensively studied this object, revealing unprecedented details about its structure and composition.

The progenitor star of this spectacular nebula was once a main-sequence star several times more massive than our Sun. As it exhausted its hydrogen fuel supply, the star evolved into a bloated red giant with a diameter approximately 1,000 times greater than the Sun's current size. During this phase, the star began fusing progressively heavier elements in its core—helium, carbon, oxygen, and eventually elements up to iron. This process released tremendous amounts of energy, but also destabilized the star's outer layers, setting the stage for the dramatic transformation we observe today.

The Formation Timeline: A Two-Thousand-Year-Old Cosmic Event

Approximately 2,000 years ago—around the time of the Roman Empire on Earth—the dying star expelled its outer atmospheric layers in a relatively slow, equatorial outflow. This material formed the distinctive dark, doughnut-shaped band of dense gas and dust visible at the nebula's center. This circumstellar torus acts as a cosmic barrier, constraining subsequent outflows and directing them perpendicular to its plane, creating the bipolar structure we observe.

Following this initial mass loss, the star underwent a dramatic transformation. As its outer layers continued to dissipate, the extremely hot stellar core became exposed, generating powerful stellar winds traveling at velocities exceeding three million kilometers per hour (1.8 million miles per hour). These supersonic winds collided with the previously expelled slower-moving material, creating shock waves that sculpted the intricate filaments, clumps, and cavities visible throughout the nebula's lobes.

The Central Engine: One of the Universe's Hottest Stars

At the heart of the Butterfly Nebula lies an extraordinarily hot white dwarf star with a surface temperature of approximately 250,000 degrees Celsius (450,000 degrees Fahrenheit)—nearly 45 times hotter than the Sun's surface. This extreme temperature, identified through spectroscopic analysis by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2009, indicates that the progenitor star was quite massive, likely between 5 and 8 solar masses before shedding its outer layers.

The white dwarf remained hidden from astronomers for decades, obscured by the dense equatorial dust torus at the nebula's center. Only with Hubble's Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3), installed during the final servicing mission in 2009, were astronomers able to penetrate the dust and directly observe this stellar remnant. The star's intense ultraviolet radiation ionizes the surrounding gases, causing them to fluoresce in the spectacular colors we observe—a process that transforms the Butterfly Nebula into what astronomers classify as an emission nebula.

"The Butterfly Nebula represents a cosmic laboratory where we can study the complex physics of stellar winds, shock waves, and the chemical enrichment of the interstellar medium. Each element we detect in these nebulae—the oxygen, nitrogen, carbon, and heavier elements—will eventually become incorporated into future generations of stars and planets," explains research from the Astrophysical Journal on planetary nebula evolution.

Decoding the Colors: Chemical Composition Revealed Through Light

The stunning colors visible in images of the Butterfly Nebula aren't merely artistic choices—they represent genuine scientific data about the nebula's chemical composition. The Gemini South image employs a different color calibration than Hubble's famous 2009 portrait, each revealing complementary information about the nebula's structure and chemistry. In Gemini's rendering, rich red hues indicate regions of ionized hydrogen, the most abundant element in the universe, while blue regions highlight ionized oxygen.

Hubble's color scheme, by contrast, assigns red to ionized nitrogen and white to ionized sulfur, revealing different aspects of the nebula's chemical stratification. This multi-wavelength approach allows astronomers to map how different elements are distributed throughout the nebula, providing insights into the nuclear fusion processes that occurred within the progenitor star. Beyond hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, and sulfur, the nebula contains traces of carbon, iron, neon, and numerous other elements—all forged in the nuclear furnace of the dying star and now destined for cosmic recycling into future stellar systems.

The Gemini Observatory: Twenty-Five Years of Discovery

The National Science Foundation's Gemini Observatory consists of twin 8.1-meter optical and infrared telescopes strategically positioned to observe both hemispheres of the sky. Gemini North, located atop Mauna Kea in Hawaii, celebrated its 25th anniversary in June 2024, while Gemini South, situated at Cerro Pachón in Chile's Atacama Desert, reached this milestone more recently. Together, these instruments have contributed to countless astronomical discoveries, from characterizing exoplanet atmospheres to studying the most distant galaxies in the universe.

The observatory's location in the Chilean Andes provides exceptional observing conditions, with more than 300 clear nights per year and minimal atmospheric turbulence. This combination of cutting-edge instrumentation and ideal observing conditions has made Gemini South one of the world's premier astronomical facilities, capable of producing images that rival or exceed those from space-based telescopes in certain wavelengths.

Cosmic Context: The Transient Nature of Everything

The Butterfly Nebula serves as a powerful reminder of the impermanence of cosmic structures at all scales. While the nebula appears static in human timescales, it is actually expanding at tremendous velocities, and within a few tens of thousands of years, it will dissipate into the interstellar medium, becoming indistinguishable from the general background of gas and dust between the stars. The white dwarf at its center will slowly cool over trillions of years, eventually becoming a cold, dark stellar remnant known as a black dwarf—though the universe isn't old enough yet for any black dwarfs to exist.

This cycle of stellar birth, life, and death has been occurring for billions of years and will continue for billions more. Our own Sun will undergo a similar transformation in approximately 5 billion years, swelling into a red giant that may engulf the inner planets, including Earth. The elements that currently compose our planet, our bodies, and every living thing on Earth will eventually be scattered into space, contributing to the formation of new stars, planets, and potentially new life elsewhere in the galaxy.

The Power of Modern Astronomy: Windows Into Cosmic Evolution

The ability to capture and analyze images like this new portrait of the Butterfly Nebula represents a remarkable achievement of modern science and technology. Our ancestors, gazing up at the night sky with naked eyes or primitive telescopes, could never have imagined the intricate beauty and complex physics revealed by instruments like Gemini South, Hubble, and the James Webb Space Telescope. These observatories provide not just pretty pictures, but detailed scientific data that advances our understanding of stellar evolution, nucleosynthesis, and the chemical enrichment of galaxies.

Key insights from studying planetary nebulae like NGC 6302 include:

- Stellar Evolution Models: Observations of planetary nebulae help astronomers refine theoretical models of how stars of different masses evolve and die, improving our understanding of stellar lifecycles across the universe

- Chemical Enrichment: By analyzing the abundances of different elements in planetary nebulae, astronomers can track how successive generations of stars have enriched the interstellar medium with heavier elements

- Mass Loss Mechanisms: The complex structures visible in nebulae like the Butterfly reveal the intricate physics of stellar winds, magnetic fields, and binary star interactions during the final stages of stellar evolution

- White Dwarf Properties: Studying the central stars of planetary nebulae provides crucial data about white dwarf formation, cooling rates, and the ultimate fate of intermediate-mass stars

Looking Forward: The Future of Planetary Nebula Research

As astronomical instrumentation continues to advance, our ability to study objects like the Butterfly Nebula in unprecedented detail will only improve. Next-generation facilities, including the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) currently under construction in Chile, will provide even sharper images and more sensitive spectroscopic capabilities. These instruments will allow astronomers to study the three-dimensional structure of planetary nebulae, track their expansion in real-time, and detect fainter features that remain invisible to current telescopes.

The Butterfly Nebula, with its distinctive morphology and relative proximity to Earth, will undoubtedly remain a prime target for future observations. Each new image and spectrum adds to our understanding not just of this particular object, but of the fundamental processes that govern stellar evolution throughout the universe. As we continue to probe the cosmos with increasingly sophisticated tools, we gain not only scientific knowledge but also a deeper appreciation for our place in the vast, ever-changing cosmic landscape.

The celebration of Gemini South's 25 years of service, marked by this spectacular new image selected by Chilean students, reminds us that astronomy is not just an academic pursuit but a source of wonder and inspiration for people of all ages and backgrounds. The Butterfly Nebula, in all its ephemeral beauty, stands as a testament to the power of scientific inquiry to reveal the hidden workings of nature and connect us to the grand cycles of cosmic evolution that have been unfolding for billions of years before us and will continue for billions of years to come.