In the cosmic theater of stellar evolution, few systems offer as dramatic a spectacle as Fomalhaut, a young triple star system located just 25 light-years from Earth. Recent observations from the Hubble Space Telescope have captured something extraordinary: evidence of catastrophic collisions between massive rocky bodies, offering astronomers a rare window into the violent processes that shape planetary systems during their formative years. This discovery, published in the prestigious journal Science, represents a significant milestone in our understanding of how solar systems evolve from chaotic debris fields into ordered planetary arrangements.

Unlike our own middle-aged Solar System, which has settled into a relatively stable configuration with planets maintaining orderly orbits around the Sun, Fomalhaut is experiencing the turbulent adolescence that our cosmic neighborhood endured billions of years ago. The system's youth—a mere 400 million years old compared to our Sun's 4.6 billion years—means it's still in the throes of planetary formation, with countless planetesimals colliding, fragmenting, and occasionally coalescing into larger bodies. What makes these recent observations particularly remarkable is that astronomers have now witnessed two separate collision events in the span of just two decades, a frequency that challenges existing theoretical models and suggests our understanding of early solar system dynamics may need significant revision.

A Triple Star System With a Violent History

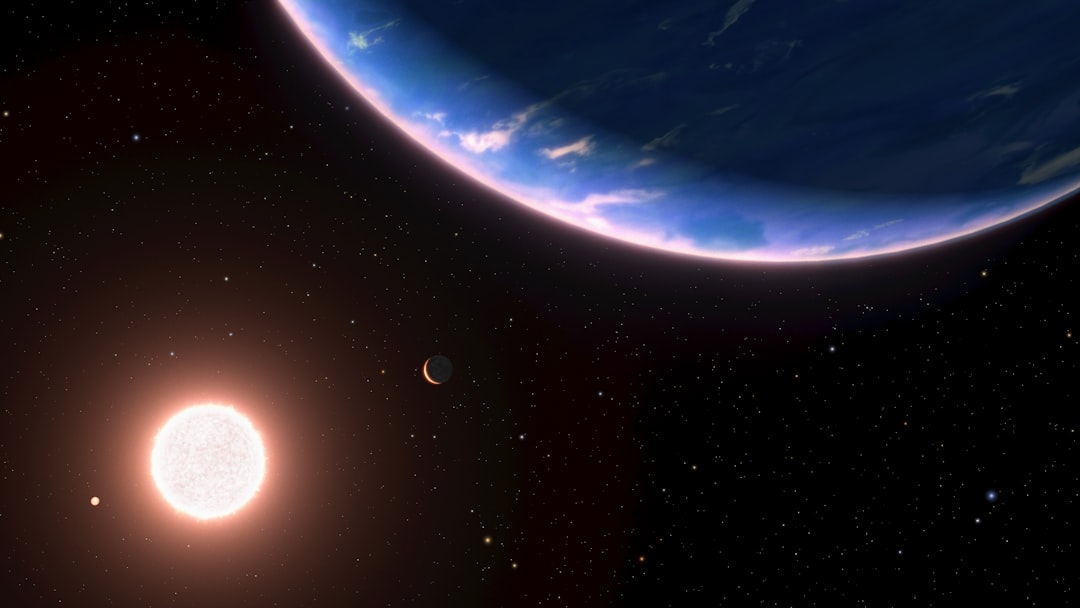

The Fomalhaut system consists of three stellar components, each playing a role in this cosmic drama. Fomalhaut A, the primary star and focus of these recent observations, outshines our Sun in both mass and luminosity, making it an ideal target for studying circumstellar debris disks. Fomalhaut B, a main-sequence star, and Fomalhaut C, a red dwarf, complete this stellar trio. The system's proximity to Earth and its prominent debris disk have made it a favorite subject for astronomers studying planetary system formation since the first direct imaging of its dust belt in 2005.

The enormous, elliptical belt of dust surrounding Fomalhaut A stretches across billions of kilometers and represents the remnants of countless collisions between comets, asteroids, and larger planetesimals—the building blocks of planets. This debris disk serves as a cosmic archaeological site, preserving evidence of the violent processes that dominated the system's early history. The structure of this disk, with its sharp inner edge and complex architecture, hints at the gravitational influence of unseen planets sculpting the distribution of material.

From Exoplanet Candidate to Collision Cloud: The Story of Fomalhaut b

The history of observations at Fomalhaut illustrates both the challenges and rewards of modern astronomy. In 2008, researchers announced what appeared to be a groundbreaking discovery: direct imaging of an exoplanet designated Fomalhaut b, seemingly orbiting within the debris ring. The scientific community celebrated this as one of the first directly imaged planets beyond our Solar System. However, subsequent observations revealed a more complex and ultimately more interesting story.

As astronomers continued monitoring Fomalhaut b over the following years, its behavior became increasingly puzzling. The object was fading in optical wavelengths and failed to appear in infrared observations—characteristics inconsistent with a planet reflecting starlight. By the mid-2010s, the evidence had mounted: Fomalhaut b was not a planet at all, but rather an expanding cloud of dust generated by the catastrophic collision of two large planetesimals. This realization transformed a story of planetary discovery into something potentially more valuable: direct observation of the violent collisional processes that build—and destroy—worlds.

Witnessing Cosmic Violence: The Discovery of Two Collision Events

The research team, led by Paul Kalas, an Adjunct Professor of Astronomy at UC Berkeley, has now identified not one but two distinct collision events in the Fomalhaut system. These objects, formally designated as circumstellar source 1 (cs1, the original Fomalhaut b) and circumstellar source 2 (cs2), represent snapshots of planetary violence frozen in time by the speed of light. Their study, published in Science under the title "A second planetesimal collision in the Fomalhaut system," provides unprecedented insight into the frequency and nature of collisions in young stellar systems.

"This is certainly the first time I've ever seen a point of light appear out of nowhere in an exoplanetary system," said Paul Kalas. "It's absent in all of our previous Hubble images, which means that we just witnessed a violent collision between two massive objects and a huge debris cloud unlike anything in our own Solar System today. Amazing!"

The sudden appearance of cs2 in 2023 observations, when it had been completely absent in previous imaging campaigns, demonstrates the dynamic nature of the Fomalhaut system. Meanwhile, cs1 had disappeared from the most recent images, supporting the interpretation that these are indeed transient dust clouds that expand, dissipate, and eventually become indistinguishable from the background debris disk. This behavior provides compelling evidence against the exoplanet hypothesis and firmly establishes both sources as collision-generated phenomena.

The Physics of Catastrophic Collisions

Understanding what happens when two 30-kilometer planetesimals collide at orbital velocities requires appreciating the immense energies involved. These impacts release energy equivalent to millions of nuclear weapons, instantly vaporizing and pulverizing rock that took millions of years to accumulate. The resulting debris cloud expands rapidly, with dust particles ranging from microscopic grains to boulder-sized fragments. Radiation pressure from the nearby star then acts on these particles, pushing smaller grains outward while larger fragments remain closer to the collision site, creating the observable structure that Hubble has captured.

The research team estimates that each 30-kilometer planetesimal experiences approximately 900 shattering events—smaller collisions that chip away material—before suffering a catastrophic impact that completely destroys it. These shattering collisions gradually erode the planetesimals while simultaneously coating their surfaces with regolith, a layer of loose, fragmented material similar to the dusty surface of our Moon. When catastrophic collisions finally occur, this accumulated regolith is released into space, contributing significantly to the observed dust clouds.

Statistical Anomalies and Theoretical Implications

Perhaps the most puzzling aspect of these observations is their timing and location. Theoretical models of debris disk evolution predict that catastrophic collisions between 30-kilometer objects should occur approximately once every 100,000 years in a system like Fomalhaut. Yet astronomers have now observed two such events separated by merely 20 years—a frequency that is orders of magnitude higher than predicted. As Kalas noted, if we could watch a time-lapse of the past 3,000 years, the Fomalhaut system would be "sparkling with these collisions."

The spatial proximity of cs1 and cs2 compounds this mystery. Both collision clouds appeared in the inner region of the outer debris belt, relatively close to one another in cosmic terms. If collisions were truly random events distributed throughout the disk, we would expect to find them scattered more widely. This clustering suggests the presence of dynamical mechanisms concentrating planetesimals in specific regions of the disk.

The Hidden Planet Hypothesis

One compelling explanation for the enhanced collision rate involves the gravitational influence of an undetected exoplanet. Planets can trap planetesimals in mean-motion resonances—orbital configurations where the planetesimal completes a specific number of orbits for each orbit of the planet. These resonances create regions of enhanced density where collisions become more frequent. The asteroid belt in our own Solar System shows similar patterns, with Jupiter's gravitational influence creating gaps and clusters through resonant interactions.

The research team notes that the intermediate debris belt around Fomalhaut shows misalignment relative to the outer belt, a feature that could result from planetary perturbations. However, definitively proving the existence of such a planet will require additional observations and careful modeling of the system's dynamics. The search for this hypothetical world represents one of the exciting frontiers opened by these collision observations.

Implications for Planetary Science and Exoplanet Detection

The Fomalhaut observations carry significant implications that extend far beyond this single system. First, they provide a natural laboratory for studying planetesimal composition and behavior under conditions impossible to replicate in terrestrial laboratories. As co-author Mark Wyatt from the University of Cambridge explained, these observations allow researchers to estimate both the size of colliding bodies and their abundance in the disk—information nearly impossible to obtain through other means. The team's analysis suggests approximately 300 million planetesimals of similar size orbit within the Fomalhaut system, providing statistical constraints for models of planetary system formation.

Second, these findings offer crucial context for understanding Earth's own formation history. Our Solar System experienced a similar phase of intense bombardment, with countless collisions gradually building the terrestrial planets while leaving the asteroid belt as a fossil record of this violent era. The Late Heavy Bombardment, which occurred approximately 4 billion years ago, may have resembled the conditions we now observe at Fomalhaut, though our evidence for this ancient event comes from lunar crater counts rather than direct observation.

A Cautionary Tale for Exoplanet Hunters

The Fomalhaut saga also serves as an important cautionary tale for future exoplanet detection missions. As Kalas noted, "Fomalhaut cs2 looks exactly like an extrasolar planet reflecting starlight." The fact that a dust cloud can masquerade as a planet for years highlights the challenges facing next-generation telescopes designed to directly image Earth-like worlds around distant stars. Missions like the proposed Habitable Worlds Observatory will need robust methods for distinguishing genuine planets from transient collision debris.

This challenge becomes particularly acute when searching for planets in young systems, where collision rates remain elevated. Astronomers will need to conduct multi-epoch observations spanning years or decades to confirm that candidate planets maintain consistent brightness and positions, rather than fading and dispersing like cs1 and cs2. The development of sophisticated models predicting dust cloud evolution will be essential for interpreting future observations.

Future Observations and Unanswered Questions

The research team has planned an ambitious observational campaign to monitor cs2's evolution over the next three years using both Hubble and the James Webb Space Telescope. These observations will track changes in the cloud's shape, brightness, and orbital motion, providing unprecedented detail about how collision debris evolves over time. Will the cloud maintain its compact appearance, or will it stretch into an elongated, comet-like structure as radiation pressure pushes dust particles outward? Will the cloud brighten as larger fragments continue fragmenting, or fade as material disperses?

The James Webb Space Telescope's near-infrared capabilities will be particularly valuable for characterizing the dust grain sizes and composition. Of special interest is the potential detection of water ice within the debris cloud. Water's presence and behavior in young planetary systems remains a crucial question for understanding how Earth and other worlds acquired their oceans. If water ice can survive the violent conditions of planetesimal collisions, it provides a mechanism for delivering water to forming planets—a process that may have been essential for making Earth habitable.

Connecting Past, Present, and Future

The Fomalhaut observations remind us that planetary systems are not static, unchanging arrangements but rather dynamic environments that evolve over billions of years. Our Solar System's current tranquility—with planets maintaining stable orbits and collision events relegated to occasional asteroid impacts—represents just one phase in a long developmental arc. By studying systems like Fomalhaut, astronomers gain insight into our own cosmic origins and the processes that transformed a chaotic cloud of gas and dust into the ordered system we inhabit today.

These findings also underscore the value of long-term astronomical monitoring programs. The discovery of cs2 was only possible because astronomers had been systematically observing Fomalhaut for nearly two decades, building an archive of images that revealed the sudden appearance of the new collision cloud. As telescope technology continues advancing and observational archives grow deeper, we can expect similar serendipitous discoveries that challenge our understanding and reveal new aspects of cosmic evolution.

The story of Fomalhaut—from exoplanet candidate to collision laboratory—illustrates the self-correcting nature of science and the importance of maintaining flexible interpretations as new evidence emerges. What began as an apparent planetary discovery has transformed into something potentially more valuable: a window into the violent, creative processes that build worlds. As we continue observing this remarkable system, each new collision, each expanding dust cloud, teaches us something fundamental about how planetary systems—including our own—come to be.