In a stunning reversal that challenges over a decade of scientific consensus, new analysis of NASA's Cassini spacecraft data suggests that Titan, Saturn's enigmatic largest moon, may not harbor a global subsurface ocean as previously believed. Instead, this frozen world appears to contain a complex interior of ice and slush, punctuated by dynamic pockets of warm liquid water that cycle between the rocky core and the surface—a finding that fundamentally reshapes our understanding of one of the solar system's most Earth-like bodies.

Published on December 17, 2025, in the prestigious journal Nature, this groundbreaking research demonstrates the enduring value of archived planetary data. By applying sophisticated modern analysis techniques to measurements collected nearly two decades ago, scientists at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory have uncovered a geological narrative far more complex than the simple ocean model that dominated Titan science since 2008.

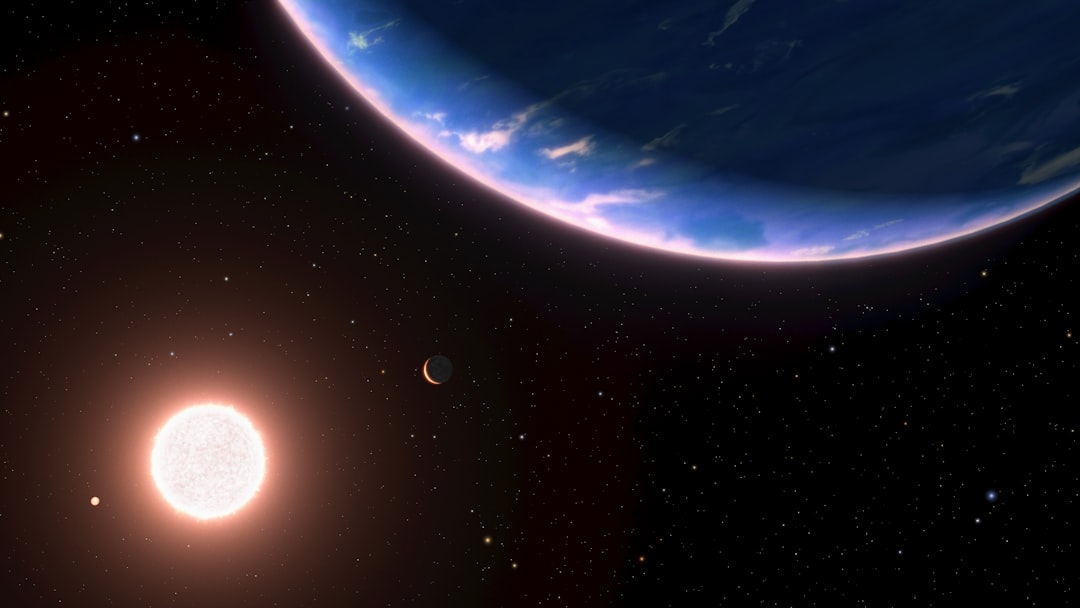

The implications extend far beyond academic interest. With NASA's Dragonfly mission scheduled to launch around 2028, understanding Titan's true internal structure becomes crucial for targeting the most promising locations to search for potential biosignatures on this hydrocarbon-rich world that many scientists consider one of the best candidates for hosting exotic forms of life in our cosmic neighborhood.

Revisiting the Ocean Hypothesis: How Cassini Changed Everything

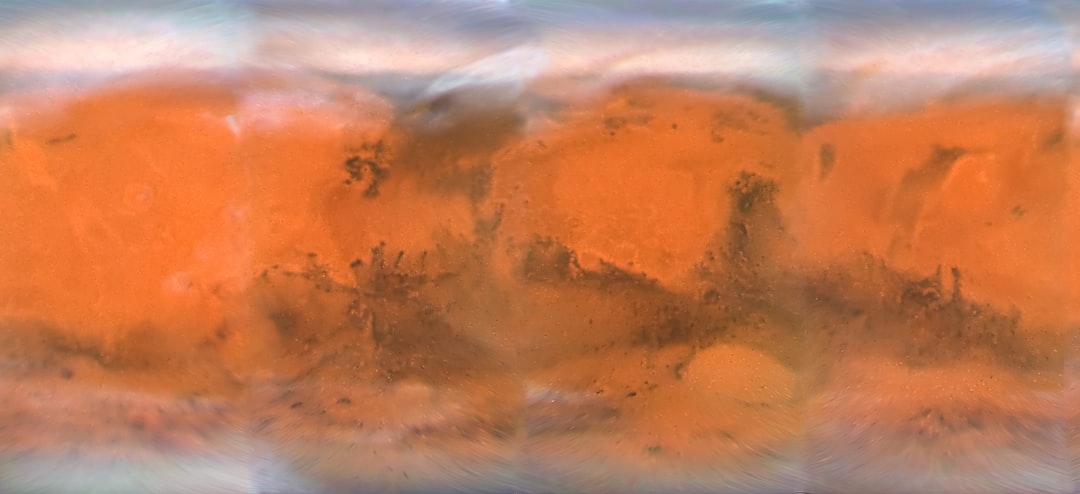

When the Cassini-Huygens mission began its systematic exploration of the Saturnian system in 2004, Titan immediately captured scientific imagination. With its thick nitrogen atmosphere, complex organic chemistry, and surface lakes of liquid methane and ethane, this moon—larger than the planet Mercury—represented a frozen laboratory for studying prebiotic chemistry. But the most tantalizing discovery came in 2008, when gravitational measurements suggested something even more remarkable: a global subsurface ocean of liquid water hidden beneath the moon's icy crust.

The evidence seemed compelling. As Titan completes its 16-day orbit around Saturn, the gas giant's immense gravitational pull creates tidal forces that stretch and compress the moon in a phenomenon known as tidal flexing. During Cassini's numerous flybys, scientists measured subtle changes in the spacecraft's velocity by analyzing the Doppler shift of radio signals transmitted between the probe and Earth. These velocity variations revealed perturbations in Titan's gravitational field that appeared consistent with a deformable interior—specifically, a liquid ocean that could flex more readily than solid ice.

The prevailing model suggested that tidal heating—the friction generated by Saturn's gravitational kneading—produced enough warmth to maintain a liquid water ocean sandwiched between Titan's rocky core and its icy outer shell. This ocean, scientists estimated, could be up to 100 kilometers deep, making it one of the largest bodies of liquid water in the solar system. The discovery placed Titan alongside Jupiter's moon Europa and Saturn's moon Enceladus as prime targets in the search for extraterrestrial life.

Advanced Analysis Reveals a More Complex Interior

The new research, led by JPL postdoctoral researcher Flavio Petricca, employed cutting-edge signal processing techniques to extract previously hidden information from Cassini's gravitational data. By developing novel methods to filter out instrumental noise and account for various sources of uncertainty, the team achieved unprecedented precision in measuring Titan's tidal dissipation—essentially, how much energy the moon loses as it flexes under Saturn's gravitational influence.

What they discovered was surprising: Titan exhibits greater energy dissipation than the liquid ocean model could explain. This finding pointed toward a different internal structure—one dominated by a slushy mixture of ice and water rather than a purely liquid ocean. In this revised model, Titan's interior consists of multiple layers of high-pressure ice phases mixed with liquid water in varying proportions, creating a heterogeneous structure that can both flex under tidal forces and dissipate energy more efficiently than a simple liquid layer.

"This research underscores the power of archival planetary science data. It is important to remember that the data these amazing spacecraft collect lives on so discoveries can be made years, or even decades, later as analysis techniques get more sophisticated. It's the gift that keeps giving," explained Julie Castillo-Rogez, a senior research scientist at JPL.

The technical achievement here cannot be overstated. The Cassini mission ended in 2017 with a dramatic plunge into Saturn's atmosphere, yet its scientific legacy continues to yield discoveries. This demonstrates a crucial principle in planetary science: the initial analysis of mission data often represents just the beginning of what we can learn from these billion-dollar investments in space exploration.

Understanding Titan's Slushy Interior Structure

The revised model of Titan's interior presents a fascinating geological architecture. Rather than distinct layers of rock, liquid water, and ice, the moon appears to contain a gradient of increasingly solid material from its rocky core outward. Near the core, where temperatures may reach several hundred degrees Celsius due to radioactive decay and residual heat from Titan's formation, pockets of liquid water exist within a matrix of high-pressure ice.

These aren't the familiar ice cubes from your freezer. Under the extreme pressures found deep within Titan—potentially reaching 10,000 times Earth's atmospheric pressure—water ice transforms into exotic crystalline structures known as high-pressure ice phases. These include Ice VI and Ice VII, which have different molecular arrangements and physical properties than ordinary ice. Mixed with liquid water, they create a slush with unique rheological properties that allow it to deform under stress while still maintaining structural integrity.

As you move outward from the core, the proportion of liquid decreases and the ice becomes increasingly solid, eventually transitioning to the more familiar water ice that comprises Titan's outer shell. This shell, estimated to be several tens of kilometers thick, provides the rigid surface upon which Titan's complex surface geology plays out—including the famous methane lakes that dot the polar regions and the vast equatorial dune fields composed of organic particles.

The Cycling of Water and Nutrients

One of the most intriguing aspects of the new model involves convective cycling within Titan's slushy interior. Petricca and his colleagues propose that warm pockets of liquid water near the rocky core can rise through the overlying layers, carrying dissolved minerals and other materials toward the surface. This process, driven by temperature and density differences, creates a dynamic system that could transport nutrients from the deep interior to the crust over geological timescales.

"While Titan may not possess a global ocean, that doesn't preclude its potential for harboring basic life forms, assuming life could form on Titan. In fact, I think it makes Titan more interesting. Our analysis shows there should be pockets of liquid water, possibly as warm as 20 degrees Celsius (68 degrees Fahrenheit), cycling nutrients from the moon's rocky core through slushy layers of high-pressure ice to a solid icy shell at the surface," noted Petricca.

This cycling mechanism could have profound implications for astrobiology. While a global ocean would provide a large, stable environment for potential life, it might also be isolated from the energy sources and organic materials abundant on Titan's surface. The slushy interior model, by contrast, suggests a more dynamic system where water, minerals, and potentially organic compounds could mix and interact over time, creating chemical gradients and interfaces that some astrobiologists consider favorable for the emergence of life.

Implications for the Search for Life Beyond Earth

The revelation that Titan lacks a global ocean might initially seem disappointing for those hoping to find life in the outer solar system. However, the reality proves more nuanced. The diversity of aqueous environments suggested by the new model—ranging from warm liquid pockets to slushy transition zones to surface interactions with organic materials—potentially offers more varied habitats than a single, homogeneous ocean layer.

Consider the key ingredients that scientists believe necessary for life as we know it:

- Liquid water: Present in pockets throughout Titan's interior, with temperatures potentially reaching a comfortable 20°C in some regions

- Energy sources: Provided by tidal heating, radioactive decay in the rocky core, and chemical reactions between water and minerals

- Organic molecules: Abundant on Titan's surface, where atmospheric chemistry produces complex hydrocarbons including tholins—organic compounds considered important precursors to life

- Mineral nutrients: Available from the rocky core and potentially transported upward through convective cycling

- Time: Titan has existed for over 4 billion years, providing ample opportunity for chemical evolution

The Dragonfly mission, a nuclear-powered rotorcraft scheduled to explore Titan's surface, will search for evidence of these processes. By sampling materials from impact craters, dune fields, and potentially sites where subsurface water has recently reached the surface, Dragonfly will investigate whether the chemical ingredients for life have combined in ways that produce biological signatures.

Broader Context: Ocean Worlds in Our Solar System

Even without a global ocean, Titan remains part of an elite group of ocean worlds in our solar system—bodies that contain significant amounts of liquid water, whether on their surfaces or hidden beneath icy shells. The confirmed members of this group include:

- Europa: Jupiter's moon, with a global ocean beneath an ice shell estimated at 60-150 kilometers deep

- Enceladus: Saturn's small moon, which actively vents water vapor and organic molecules from a subsurface ocean through geysers at its south pole

- Ganymede: Jupiter's largest moon, believed to have a layered ocean system with multiple ice and water layers

- Callisto: Another Jovian moon with a possible subsurface ocean

- Mimas: Recently discovered to likely have a global ocean despite its heavily cratered, ancient-looking surface

The European Space Agency's JUICE mission and NASA's upcoming Europa Clipper will study several of these worlds in detail, helping scientists understand the diversity of ocean environments in our cosmic neighborhood and refining our search strategies for life beyond Earth.

Technical Advances Enabling the Discovery

The breakthrough in understanding Titan's interior structure resulted from advances in data analysis techniques that weren't available when Cassini's measurements were first obtained. Specifically, the JPL team developed new algorithms for extracting gravitational signals from noisy radio Doppler data, accounting for various sources of interference including:

- Variations in Earth's atmosphere affecting radio signal propagation

- Uncertainties in Cassini's trajectory and attitude

- Gravitational perturbations from Saturn's other moons

- Instrumental drift and calibration issues

- Solar radiation pressure effects on the spacecraft

By carefully modeling and removing these noise sources, the researchers achieved measurements of Titan's tidal Love number—a parameter describing how much a body deforms under tidal forces—with unprecedented precision. This allowed them to distinguish between competing models of Titan's interior that previous analyses couldn't definitively separate.

The work exemplifies how investments in computational techniques and data science continue to extract value from existing datasets. As machine learning and artificial intelligence tools become more sophisticated, we can expect similar revelations from the archives of other planetary missions, potentially revolutionizing our understanding of worlds we thought we already knew.

Looking Forward: The Future of Titan Exploration

The new findings about Titan's interior will directly inform the planning and execution of the Dragonfly mission. Scheduled to arrive at Titan in the mid-2030s, this innovative spacecraft will use its octocopter design to fly between multiple sites across Titan's surface, taking advantage of the moon's thick atmosphere and low gravity to achieve unprecedented mobility for a planetary lander.

Understanding that Titan's interior consists of slushy ice rather than a global ocean helps mission planners identify the most promising targets for investigation. Sites where recent cryovolcanic activity may have brought subsurface materials to the surface become particularly interesting, as they could provide direct samples of the warm water pockets and dissolved minerals from Titan's deep interior.

The mission will also investigate Titan's prebiotic chemistry by analyzing organic molecules on the surface, studying the interaction between atmospheric products and surface materials, and searching for evidence of more complex chemistry that might indicate biological processes. The Dragonfly science team continues to refine their investigation strategies based on new discoveries like this one.

Lessons for Planetary Science

This discovery reinforces several important principles for planetary science and space exploration:

First, initial interpretations of data are rarely the final word. As analytical techniques improve and our theoretical understanding deepens, we must remain open to revising even well-established conclusions. The scientific method demands this flexibility, and the history of planetary science is filled with examples where new analysis overturned previous consensus.

Second, archival data represents an enduring scientific resource. The billions of dollars invested in missions like Cassini continue generating returns long after the spacecraft cease operations. This argues for robust data archiving practices and continued funding for data analysis even after missions end.

Third, complexity is the rule rather than the exception in planetary science. Simple models—like a moon with distinct layers of rock, liquid ocean, and ice—often prove inadequate when confronted with detailed observations. Real planetary bodies exhibit intricate structures shaped by billions of years of geological evolution, and understanding them requires sophisticated analysis and modeling.

As we continue exploring our solar system and searching for life beyond Earth, discoveries like this remind us that the universe consistently surprises us with its complexity and ingenuity. Titan, whether it harbors a global ocean or a slushy interior with dynamic water pockets, remains one of the most fascinating worlds in our cosmic neighborhood—a frozen laboratory where chemistry, geology, and possibly biology interact in ways we're only beginning to understand.

The complete research findings are available in the paper by Flavio Petricca and colleagues, published in Nature, titled "Titan's strong tidal dissipation precludes a subsurface ocean," representing another chapter in humanity's ongoing quest to understand the diverse worlds that share our solar system.