In a remarkable achievement that could reshape humanity's future among the stars, Chinese researchers have successfully demonstrated that mammalian reproduction remains viable after spaceflight. A female mouse that spent two weeks aboard China's Tiangong space station has given birth to nine healthy offspring, with six surviving to thrive under their mother's care—a milestone that addresses one of the most fundamental questions about long-term human space exploration.

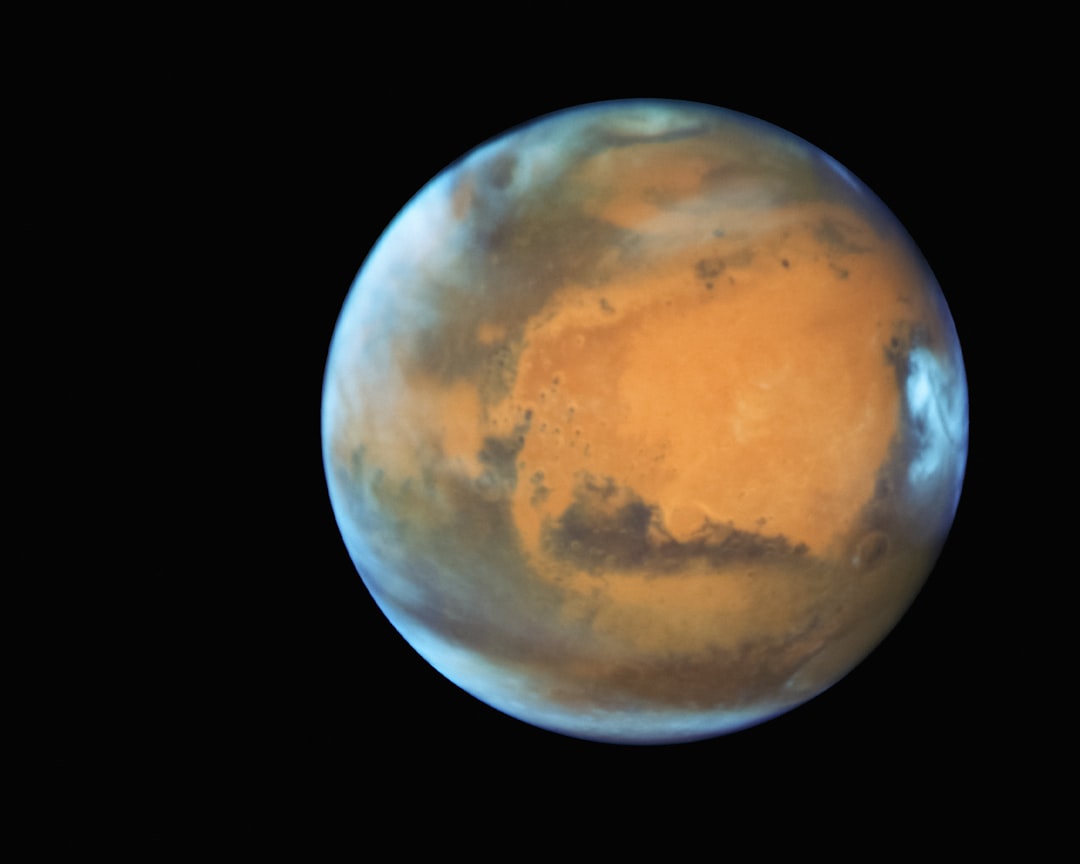

The experiment, conducted as part of China's Shenzhou-19 mission, sent four carefully selected mice—designated by numbers 6, 98, 154, and 186—on a journey approximately 400 kilometers above Earth's surface. From October 31 to November 14, these rodent astronauts experienced the harsh realities of orbital existence: microgravity, elevated cosmic radiation levels, and the physiological stresses that come with living beyond our planet's protective embrace. What happened next, however, proved even more significant than the journey itself.

On December 10, less than a month after returning to Earth, one of the female mice successfully delivered a litter of nine pups. This seemingly simple biological event carries profound implications for humanity's ambitions to establish permanent settlements on the Moon and Mars, as reported by researchers at the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The successful birth and continued development of these "space pups" provides crucial evidence that short-duration spaceflight may not irreparably damage mammalian reproductive capabilities.

Why Mice Matter: The Scientific Rationale Behind Rodent Astronauts

The choice to send mice into orbit wasn't arbitrary—it represents decades of scientific understanding about model organisms in biological research. Mice share approximately 95% of their genes with humans, making them invaluable proxies for understanding how space affects mammalian biology. Their relatively short reproductive cycles, typically 19-21 days, allow researchers to observe multiple generations within practical timeframes, something impossible with human subjects.

According to NASA's biological research programs, mice respond to physiological stresses—including radiation exposure, altered gravity, and environmental changes—in ways that often mirror human responses. If the extreme conditions of spaceflight were to compromise fundamental reproductive processes, these effects would manifest first in rapidly reproducing species like mice.

"The significance of our discovery lies in demonstrating that short-term spaceflight didn't damage the mouse's ability to reproduce normally," explained Wang Hongmei, a researcher at the Chinese Academy of Sciences' Institute of Zoology. "This opens the door to understanding whether longer missions might pose different challenges."

Previous experiments have explored pieces of this puzzle. In 2019, researchers successfully used freeze-dried mouse sperm that had been stored on the International Space Station for up to nine months to fertilize eggs on Earth, producing healthy offspring. However, this new study represents a crucial advancement: it demonstrates that a female mouse exposed to the complete spaceflight experience—launch stresses, microgravity, radiation, and re-entry—can still conceive and bear healthy young after returning to Earth.

Surviving the Unexpected: Crisis Management in Orbit

The mission faced significant challenges that tested both the experimental design and the ground team's problem-solving abilities. When the return schedule for Shenzhou-20 changed unexpectedly, the mice confronted an extended orbital stay with dwindling supplies. This scenario, while unplanned, provided valuable insights into emergency life support protocols for biological experiments in space.

The ground control team at the China National Space Administration rapidly mobilized to address the potential food shortage. They conducted extensive testing on various emergency rations, including:

- Compressed biscuits: High-calorie human food that could potentially sustain the mice but risked digestive complications

- Corn kernels: Natural food source that provided tooth-grinding opportunities but lacked complete nutrition

- Hazelnuts: Nutrient-dense option that posed challenges for consistent consumption

- Soy milk: Ultimately selected as the safest emergency supplement due to its digestibility and nutritional profile

Water delivery presented another technical challenge. Engineers pumped fresh water into the habitat through an external port, a delicate operation requiring precise coordination between ground control and the station's systems. Meanwhile, an artificial intelligence monitoring system tracked the mice continuously, analyzing their movements, eating patterns, and sleep cycles in real-time. This AI system proved crucial for predicting when supplies would reach critical levels, allowing the team to implement contingency plans before emergencies arose.

Creating Earth-Like Conditions in an Alien Environment

Throughout their orbital residence, the four mice lived in a carefully engineered habitat designed to maintain some semblance of terrestrial normalcy within the utterly foreign environment of space. The circadian rhythm management system activated lights at 7:00 AM and deactivated them at 7:00 PM Beijing time, preserving the day-night cycle that regulates countless biological processes in mammals.

The mice's diet consisted of nutritionally balanced pellets specifically formulated to be intentionally hard, satisfying their instinctive need to grind their continuously growing incisors. A directional airflow system maintained habitat cleanliness by channeling loose hair and waste particles into collection containers—a critical feature given that debris behaves unpredictably in microgravity environments.

The Next Generation: Monitoring Space Pups for Hidden Effects

The birth of nine healthy pups marks the beginning, not the conclusion, of this research. Scientists will now conduct comprehensive longitudinal studies on these offspring, searching for subtle effects that might not be immediately apparent. Research protocols will include:

- Growth curve analysis: Comparing developmental milestones against control groups to detect any deviations in physical maturation

- Behavioral assessments: Evaluating cognitive function, motor skills, and social behaviors for signs of neurological impacts

- Reproductive capability testing: Determining whether these second-generation mice can themselves produce healthy offspring, revealing potential multi-generational effects

- Genetic screening: Examining DNA for mutations or epigenetic changes that might have resulted from maternal space exposure

- Immunological studies: Assessing whether space radiation exposure affected the development of the immune system

According to research published in Nature's space biology section, the effects of space radiation on reproductive cells remain one of the most significant unknowns in long-duration spaceflight. Cosmic rays can penetrate spacecraft shielding and potentially damage DNA in eggs and sperm, with consequences that might only become apparent in subsequent generations.

Implications for Human Space Exploration and Settlement

This experiment addresses questions that extend far beyond rodent biology. Before humanity attempts multi-year missions to Mars or establishes permanent lunar bases, we must understand whether mammalian reproduction functions normally in space environments or after space exposure. The stakes couldn't be higher: any permanent human presence beyond Earth will eventually require successful reproduction.

Current plans by NASA's Artemis program and other international space agencies envision sustained lunar habitation within the next decade. Mars missions, likely occurring in the 2030s or 2040s, could last two to three years. For such endeavors to transition from temporary expeditions to genuine colonization, numerous biological questions demand answers:

- Can mammals conceive in reduced gravity environments (one-sixth Earth gravity on the Moon, three-eighths on Mars)?

- Does fetal development proceed normally without Earth's gravitational influence?

- Will cosmic radiation exposure during pregnancy cause developmental abnormalities?

- Can newborns develop proper bone density and muscle strength in low-gravity conditions?

- Are there cumulative effects across multiple generations born in space?

The Chinese experiment doesn't answer all these questions—the mice spent only two weeks in space and gave birth after returning to Earth's gravity. However, it provides an essential data point: short-duration spaceflight exposure doesn't prevent subsequent successful reproduction in mammals. This finding suggests that astronauts returning from missions to the Moon or even Mars might not face permanent reproductive impairment.

Building on Previous Space Reproduction Research

This achievement builds upon decades of space biology research. Previous experiments have successfully bred various organisms in space, including Caenorhabditis elegans (roundworms), fruit flies, and fish. However, mammals present unique challenges due to their complex reproductive systems, extended gestation periods, and the crucial role gravity plays in fetal development.

The 2019 study that successfully used space-stored sperm represented a significant milestone, but it left critical questions unanswered about female reproductive biology. Eggs are more complex than sperm cells and potentially more vulnerable to radiation damage. The process of ovulation, fertilization, and early embryonic development involves intricate hormonal cascades that might be disrupted by spaceflight stresses.

By demonstrating that a female mouse can undergo spaceflight and subsequently reproduce normally, Chinese researchers have filled a crucial gap in our understanding. The next logical steps involve studying conception, gestation, and birth actually occurring in space—experiments that present enormous technical and ethical challenges but may be necessary before humans attempt the same.

Future Directions: From Mice to Humans

The path from successful mouse reproduction to confident human space reproduction remains long and complex. Future research must address progressively more challenging scenarios: longer spaceflight durations, conception occurring in microgravity, complete gestational cycles in space, and multi-generational studies spanning years or decades.

International collaboration will prove essential. The European Space Agency's space medicine programs, NASA's biological research initiatives, and China's expanding space station capabilities can collectively tackle questions too large for any single nation to address alone.

As humanity stands on the threshold of becoming a multi-planetary species, experiments like this mouse reproduction study provide the foundational knowledge necessary for that transformation. One mouse giving birth to nine pups may seem modest compared to the grand visions of Mars cities and lunar colonies. Yet in the careful progression of science, such small steps illuminate the path forward, revealing both the possibilities and challenges that await us among the stars.

The healthy development of these six surviving space pups offers hope that the biological barriers to space settlement, while formidable, may not be insurmountable. Their continued growth and the reproductive success of future generations will help determine whether humanity's cosmic ambitions align with biological reality—whether we can not just visit space, but truly live there, generation after generation, building civilizations beyond the world that gave us birth.