In the vast cosmic theater where stars meet their dramatic ends, most stellar deaths follow a familiar script: a catastrophic explosion that scatters debris across space in chaotic, billowing clouds. But supernova remnant Pa 30 has rewritten the playbook entirely. This enigmatic celestial object, connected to a mysterious "guest star" observed by ancient Chinese and Japanese astronomers in 1181 CE, displays a structure so unusual that it has puzzled scientists for years—until now.

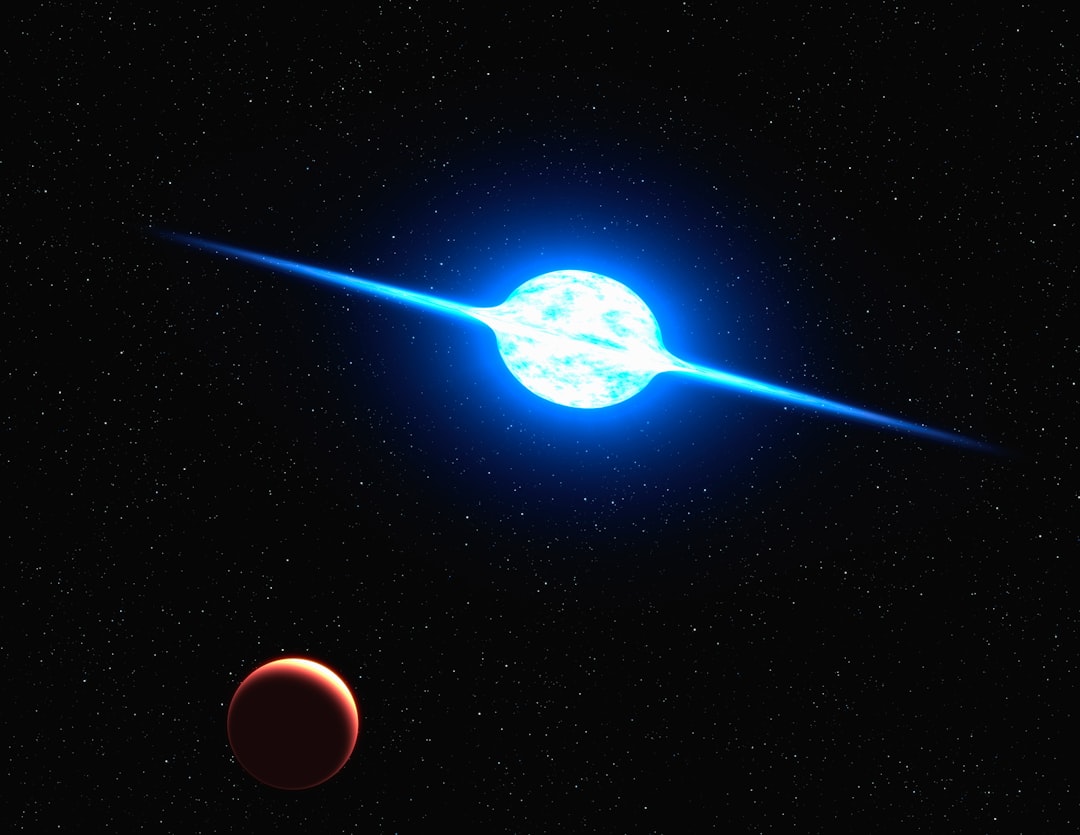

Rather than the typical turbulent, cauliflower-shaped debris field that characterizes most supernova remnants, Pa 30 presents an almost impossibly elegant appearance. Long, ruler-straight filaments radiate outward from its center like frozen firework trails, creating a pattern more reminiscent of a Fourth of July sparkler captured mid-burst than the violent aftermath of stellar destruction. This remarkable geometry has now been explained by groundbreaking research from Dr. Eric Coughlin at Syracuse University, who proposes that Pa 30's progenitor star attempted to explode as a supernova—but ultimately failed to complete the detonation.

This discovery represents a fascinating window into a rare category of stellar death known as Type Iax supernovae, events where white dwarf stars experience only partial detonation rather than complete annihilation. The implications extend far beyond this single object, offering insights into nuclear physics, fluid dynamics, and the diverse ways that stars can end their lives across the cosmos.

The Puzzle of Historical Astronomy Meets Modern Astrophysics

The story of Pa 30 begins nearly a millennium ago, when observers in ancient China and Japan documented the sudden appearance of a bright new star in the constellation Cassiopeia. This "guest star" remained visible for approximately six months before fading from view—a typical duration for what we now understand to be supernova events. For centuries, the exact location and nature of this historical explosion remained a mystery, one of several documented supernovae from the medieval period that astronomers have worked to identify in modern telescopes.

When modern astronomers finally connected Pa 30 to the 1181 event, they faced an immediate conundrum. The object's appearance contradicted everything they knew about Type Ia supernovae, the class of stellar explosions that occur when white dwarf stars reach a critical mass threshold and detonate. Type Ia supernovae typically leave behind expanding shells of debris with characteristic turbulent structures, shaped by complex fluid dynamics and shock waves. Pa 30's orderly, radial filaments suggested an entirely different physical process at work.

Anatomy of a Failed Stellar Explosion

To understand what makes Pa 30 so extraordinary, we must first examine the typical death throes of a white dwarf star. These stellar remnants, roughly the size of Earth but containing the mass of our Sun, represent the final evolutionary stage for stars like our own. When a white dwarf in a binary system accretes material from a companion star, it can reach the Chandrasekhar limit—approximately 1.4 solar masses—triggering a thermonuclear explosion that completely obliterates the star.

In Pa 30's case, however, something went catastrophically wrong—or perhaps, more accurately, partially right. According to Coughlin's research, published in collaboration with data from NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory, the nuclear burning that initiated near the white dwarf's surface never achieved the conditions necessary to transition into a full supersonic detonation wave. Instead of consuming the entire star in a fraction of a second, the explosion fizzled out, leaving behind what researchers call a hyper-massive white dwarf—a surviving stellar core that exceeds the normal mass limit for such objects.

"What we're seeing in Pa 30 is essentially a star that tried to explode but couldn't quite manage it. The partial detonation left behind a remnant that's now behaving in ways we've never observed before, launching material into space at truly extraordinary velocities."

The Extraordinary Wind That Shaped a Cosmic Firework

The surviving white dwarf at Pa 30's heart didn't simply sit dormant after its failed explosion. Instead, it began generating an ultra-fast stellar wind with properties that defy conventional expectations. This wind, enriched with heavy elements forged during the aborted supernova, races outward at approximately 15,000 kilometers per second—roughly 5% the speed of light. To put this in perspective, that's fast enough to travel from Earth to the Moon in less than 30 seconds.

Critically, this wind possesses a density far greater than the surrounding interstellar medium—the tenuous gas that fills the space between stars. This extreme density contrast creates the perfect conditions for a phenomenon well-known to fluid dynamicists: the Rayleigh-Taylor instability. This same physical process shapes mushroom clouds from nuclear explosions, creates the distinctive appearance of lava lamps, and occurs whenever a heavy fluid pushes into a lighter one.

As Pa 30's dense wind slammed into the surrounding low-density gas, the Rayleigh-Taylor instability caused finger-like protrusions to develop at the interface between the two fluids. These "fingers" became the spectacular filaments that give Pa 30 its unique appearance. Each filament represents a channel where the dense stellar wind continues to flow outward, maintained and fed by the continuous outpouring from the central white dwarf.

Why Pa 30's Filaments Survived Intact

The existence of long, coherent filaments in Pa 30 raises an important question: why didn't they tear apart and become chaotic? In most supernova remnants observed by telescopes like the James Webb Space Telescope and Chandra, we see turbulent, twisted structures that bear little resemblance to orderly patterns. The answer lies in a second fluid instability that's normally at play in these cosmic explosions.

The Kelvin-Helmholtz instability, which creates the characteristic swirling patterns in clouds and ocean waves, typically acts to shred and fragment structures formed by the Rayleigh-Taylor instability. This is why smoke from a chimney starts as a coherent plume but quickly breaks up into chaotic wisps and eddies. In most supernova remnants, this secondary instability transforms any initial structure into the cauliflower-like morphology astronomers typically observe.

However, Pa 30's extreme density contrast—with the stellar wind being vastly heavier than the surrounding medium—suppressed the Kelvin-Helmholtz instability before it could fragment the filaments. The fingers of dense material simply kept extending outward, continuously fed by the central source, maintaining their structural integrity over centuries. This is analogous to a high-pressure water jet maintaining its coherence over long distances, rather than immediately dispersing into droplets.

Nuclear Tests and Cosmic Explosions: An Unexpected Connection

In a fascinating cross-disciplinary insight, Coughlin's research draws parallels with declassified photographs from the 1962 Kingfish nuclear test conducted by the United States in the Pacific Ocean. These historical images show remarkably similar filamentary patterns forming in the initial moments after detonation, before the expanding fireball evolved into the more familiar mushroom cloud shape.

The key difference between the nuclear test and Pa 30 lies in timescales and the presence of a continuous driving source. In the Kingfish explosion, the initial filamentary structure lasted only moments before secondary instabilities transformed it into chaotic turbulence. In Pa 30, the ongoing stellar wind continuously feeds and extends the filaments, preventing them from evolving into disorder. This comparison highlights how fundamental physics operates consistently across vastly different scales—from human-made explosions on Earth to cosmic events occurring across light-years of space.

Type Iax Supernovae: A Distinct Class of Stellar Death

Pa 30's failed explosion places it firmly within the category of Type Iax supernovae, a subclass of stellar explosions first recognized as distinct in the early 2000s. These events represent perhaps 5-30% of all Type Ia supernovae, though their exact frequency remains uncertain due to their relative faintness compared to their fully successful cousins.

Key characteristics of Type Iax supernovae include:

- Incomplete detonation: The thermonuclear burning fails to consume the entire white dwarf, leaving behind a surviving remnant

- Lower luminosity: These explosions are typically 10-100 times fainter than standard Type Ia supernovae, making them harder to detect

- Unusual spectroscopy: The light from Type Iax events shows distinctive signatures of partially burned nuclear material

- Surviving stellar cores: Unlike complete explosions that obliterate their progenitor stars, Type Iax events leave behind compact remnants

- Diverse outcomes: Each Type Iax supernova may produce different remnant structures depending on the exact conditions of the failed explosion

Understanding Type Iax supernovae has important implications for cosmology. Standard Type Ia supernovae serve as "standard candles" for measuring cosmic distances, a technique that led to the discovery of dark energy and earned the 2011 Nobel Prize in Physics. If a significant fraction of what appear to be Type Ia events are actually Type Iax explosions with different intrinsic brightnesses, this could introduce systematic errors into distance measurements across the universe.

Broader Implications and Future Discoveries

Coughlin's research suggests that Pa 30's distinctive filamentary structure may not be unique in the cosmos. Similar patterns might appear in other astrophysical scenarios where dense material flows into less dense surroundings at high velocities. One particularly intriguing possibility involves tidal disruption events—catastrophic encounters where stars venture too close to supermassive black holes and are torn apart by gravitational forces.

When a star is shredded by a black hole's tidal forces, the resulting debris forms an accretion disk while some material is ejected in powerful outflows. If these outflows have the right density and velocity characteristics, they might produce filamentary structures similar to Pa 30's, though on different spatial scales. Observations from next-generation telescopes like the ESA's Athena X-ray Observatory, scheduled for launch in the 2030s, may reveal whether such structures exist.

The research also opens questions about the ultimate fate of Pa 30's central white dwarf. This hyper-massive remnant exists in a theoretically unstable state, exceeding the mass that a white dwarf can normally support through electron degeneracy pressure. Over time, it may gradually lose mass through its powerful wind, eventually settling into a stable configuration. Alternatively, if it continues to accrete material from its surroundings, it might eventually achieve the conditions for a delayed, complete detonation—essentially getting a second chance at becoming a proper supernova.

A Window Into Rare Cosmic Phenomena

Pa 30 represents one of the rare instances where modern astrophysics can directly connect with historical astronomical observations, bridging nearly a thousand years of human observation. The guest star of 1181 CE, once merely a curious historical footnote, has become a detailed case study in the diverse ways that stars can meet their ends.

The object reminds us that the universe rarely conforms to our neat categories and expectations. While textbooks often present stellar evolution as a series of well-defined pathways, reality proves far more nuanced. Some stars explode completely, some fail to explode at all and quietly fade away, and some—like Pa 30's progenitor—occupy an intriguing middle ground, creating cosmic fireworks that continue to surprise and enlighten astronomers centuries after their initial outburst.

As our observational capabilities continue to advance, we can expect to discover more objects like Pa 30, each offering unique insights into the physics of stellar explosions, nuclear burning, and fluid dynamics operating at cosmic scales. These failed supernovae, dying not with a definitive bang but with a complicated whimper, leave behind structures of surprising elegance and beauty—frozen fireworks that illuminate the complexity and wonder of our universe.