In the vast cosmic theater of planetary systems, few celestial objects have puzzled astronomers quite like hot Jupiters—massive gas giants that orbit perilously close to their parent stars. A groundbreaking study published in The Astronomical Journal by researchers from The University of Tokyo has shed new light on one of exoplanetary science's most enduring mysteries: how did these scorching worlds end up in such extreme orbits, and what can their current positions tell us about their turbulent past?

The research team employed sophisticated mathematical modeling to analyze the orbital evolution of more than 500 hot Jupiters, examining whether these planets migrated inward through their protoplanetary disks during formation or arrived at their current locations through more dramatic gravitational interactions. Their findings reveal that approximately 30 of these exoplanets retain a "memory" of their migration history—orbital characteristics that don't align with conventional theories about how quickly planets should settle into circular orbits. This discovery has profound implications for our understanding of planetary system architecture and the diverse pathways through which worlds can form and evolve.

The Great Migration Debate: Two Pathways to Proximity

Understanding how hot Jupiters arrived at their current orbital positions requires examining two competing theories that have dominated exoplanetary science for decades. The first mechanism, known as disk migration, proposes that these massive planets form farther from their stars—similar to Jupiter's position in our solar system—and then gradually spiral inward while still embedded in the protoplanetary disk of gas and dust that surrounds young stars. This process occurs through gravitational interactions between the planet and the disk material, causing the planet to lose angular momentum and migrate toward its host star over timescales of hundreds of thousands to millions of years.

The alternative pathway, termed high-eccentricity migration (HEM), involves a far more violent journey. In this scenario, gravitational interactions with other massive planets or a distant stellar companion can fling a gas giant into a highly elongated, eccentric orbit. As the planet repeatedly swings close to its star at periastron (the closest point in its orbit), tidal forces gradually circularize the orbit while simultaneously causing the planet to migrate inward. This process transforms a planet on a comet-like trajectory into one following a tight, nearly circular path around its star.

The Tokyo research team developed a novel approach to distinguish between these two migration mechanisms by examining a critical factor: circularization timescales. By calculating how long it should take for tidal forces to transform a highly eccentric orbit into a circular one, and comparing this duration to the age of the planetary system, the researchers could identify which hot Jupiters likely arrived via disk migration versus high-eccentricity migration.

Decoding Planetary Memories Through Mathematical Analysis

The research methodology employed by the University of Tokyo team represents a significant advancement in how scientists analyze exoplanetary populations. Working with a comprehensive dataset of 578 Jovian-mass planets with precisely measured masses and radii, the researchers applied a series of sophisticated mathematical equations to model the tidal interactions between each planet and its host star. Central to their analysis was the empirical calibration of the tidal quality factor—a parameter that describes how efficiently tidal forces dissipate energy within a planet's interior.

This tidal quality factor is crucial because it determines how quickly a planet's eccentric orbit will circularize. Planets with lower tidal quality factors dissipate energy more efficiently, leading to faster circularization, while those with higher values retain their eccentric orbits for longer periods. By examining the current eccentricity distribution of known hot Jupiters and comparing their orbital characteristics to system ages determined through stellar evolution models, the team could identify planets whose orbits should have circularized long ago—if they had arrived via high-eccentricity migration.

"In this paper, we identified close-in Jupiters that likely arrived via disk migration by leveraging the idea that when the circularization timescale of a planet is longer than system age, HEM would not be able to complete in time," the researchers explained in their conclusions, highlighting the logical foundation of their discriminatory approach.

The results proved illuminating: while the vast majority of the 500+ hot Jupiters examined showed circularization timescales consistent with high-eccentricity migration—meaning their orbits could have evolved from highly eccentric to circular within the system's lifetime—approximately 30 hot Jupiters defied this expectation. For these exceptional worlds, the calculated time required to circularize their orbits exceeded the age of their planetary systems, strongly suggesting they never underwent the dramatic orbital evolution characteristic of HEM. Instead, these planets likely migrated inward through the more gradual disk migration process, arriving at their current positions while the protoplanetary disk was still present.

Hot Jupiters: Cosmic Oddities That Challenged Everything We Knew

To appreciate the significance of this research, one must understand why hot Jupiters have captivated astronomers since their discovery. These gas giant planets represent a class of worlds entirely absent from our own solar system, where Jupiter and Saturn orbit at comfortable distances of 5.2 and 9.5 astronomical units from the Sun, respectively. Hot Jupiters, by contrast, orbit at distances of just 0.015 to 0.1 astronomical units—closer to their stars than Mercury is to our Sun.

The discovery of the first confirmed exoplanet orbiting a Sun-like star in 1995, 51 Pegasi b, immediately upended conventional theories of planetary formation. This hot Jupiter completes an orbit around its host star in just 4.23 days, challenging the prevailing assumption that planetary systems would universally resemble our own solar system's architecture. Since that watershed moment, astronomers have confirmed the existence of approximately 500-600 hot Jupiters among the thousands of known exoplanets—roughly one-tenth of all confirmed worlds beyond our solar system.

What makes these planets "hot" is their extreme proximity to their host stars, resulting in surface temperatures that can exceed 2,000 Kelvin (3,140°F). Their orbital periods range from less than one day to about 10 days, with some of the most extreme examples completing an orbit in mere hours. These scorching conditions create exotic atmospheric phenomena, including winds exceeding thousands of miles per hour, clouds of vaporized metals, and permanent day-night temperature gradients that can span hundreds of degrees.

The Evolution of Detection Methods and Discovery Bias

In the early years of exoplanet discovery, hot Jupiters dominated the census of known worlds—not because they were necessarily more common than other types of planets, but because they were the easiest to detect. The radial velocity method, which measures the subtle wobble a planet induces in its host star's motion, is most sensitive to massive planets in close orbits. Similarly, the transit method, which detects the slight dimming of starlight when a planet passes in front of its star, favors large planets with short orbital periods that transit frequently.

As detection methods have improved and missions like NASA's Kepler Space Telescope and the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) have surveyed millions of stars, the ratio of hot Jupiters to other exoplanet types has decreased substantially. We now know that hot Jupiters are relatively rare, occurring around only about 1% of Sun-like stars. This rarity itself provides important clues about planetary formation and migration—whatever processes create hot Jupiters must be special circumstances rather than the default outcome of planet formation.

Implications for Planetary System Architecture and Formation Theory

The Tokyo team's findings have significant implications for our understanding of how planetary systems form and evolve. The identification of hot Jupiters that likely migrated through the protoplanetary disk rather than via high-eccentricity migration suggests that multiple pathways can lead to the same final configuration. This diversity in migration mechanisms may explain some of the puzzling variations observed in hot Jupiter populations, including differences in their atmospheric compositions, spin-orbit alignments, and the presence or absence of companion planets.

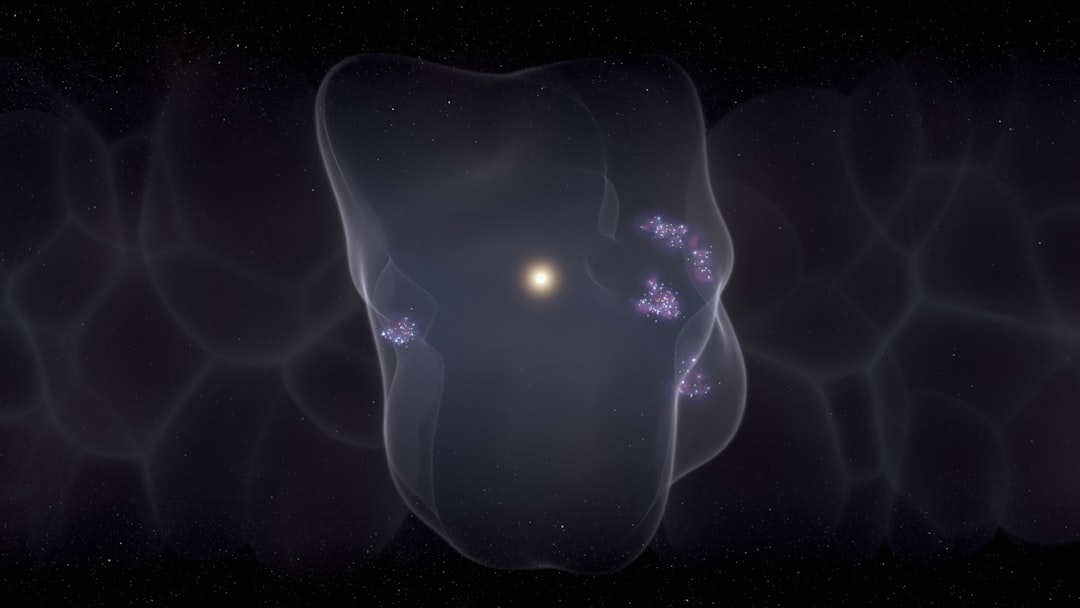

Planets that migrated through the disk would have experienced fundamentally different environmental conditions during their journey inward. They would have interacted continuously with gas and dust, potentially accreting additional material and experiencing chemical exchanges with the disk. Their migration would have been relatively gentle and controlled by the disk's lifetime, typically a few million years. In contrast, hot Jupiters that arrived via high-eccentricity migration would have experienced dramatic tidal heating during their eccentric phase, potentially altering their internal structure and atmospheric properties.

The research also highlights important connections between hot Jupiter formation and the broader architecture of planetary systems. Systems that produce hot Jupiters through high-eccentricity migration typically require the presence of additional massive planets or stellar companions to provide the necessary gravitational perturbations. The absence of such companions in systems hosting the 30 disk-migration candidates identified in this study supports the interpretation that these planets followed a different evolutionary pathway.

Future Directions: Expanding the Search for Planetary Memories

The University of Tokyo researchers emphasize that their study represents just the beginning of a more comprehensive investigation into hot Jupiter origins. Several key areas require further exploration to refine and validate their findings:

- Larger Sample Sizes: While 578 planets represents a substantial dataset, expanding the analysis to include newly discovered hot Jupiters from TESS and future missions will improve statistical confidence and may reveal additional migration patterns or subtypes within the hot Jupiter population.

- Obliquity Measurements: Studying the obliquity or tilt of hot Jupiter orbits relative to their host stars' equatorial planes can provide crucial evidence about migration mechanisms. Disk migration typically preserves alignment between planetary orbits and stellar rotation, while high-eccentricity migration often produces misaligned or even retrograde orbits.

- Protoplanetary Disk Properties: Understanding how variations in disk mass, lifetime, and structure affect migration outcomes will help refine predictions about which planetary systems should produce disk-migrated versus eccentricity-migrated hot Jupiters.

- Atmospheric Characterization: Future observations with the James Webb Space Telescope may reveal atmospheric differences between hot Jupiters that migrated via different pathways, potentially including variations in chemical composition or atmospheric escape rates.

The team specifically highlighted the importance of mining archival data from Kepler's nine-year mission and continuing to leverage TESS observations. These datasets contain information about thousands of planetary systems across a wide range of stellar types and ages, providing the statistical power needed to identify subtle patterns in hot Jupiter properties and test competing formation theories.

Broader Implications for the Search for Life Beyond Earth

While hot Jupiters themselves are far too extreme to host life as we know it—with surface temperatures that would vaporize most known materials and radiation levels that would sterilize any organic molecules—understanding their formation and migration has important implications for the search for habitable worlds. The processes that create hot Jupiters can profoundly affect the stability and habitability of other planets in the same system.

When a massive planet migrates inward through a planetary system, whether via disk migration or high-eccentricity migration, it can gravitationally disrupt the orbits of smaller, rocky planets. This disruption might eject potentially habitable worlds into interstellar space or send them plunging into their host stars. Conversely, some theoretical models suggest that the migration of gas giants could actually help deliver water and organic materials to rocky planets in the habitable zone, potentially enhancing their prospects for life.

By understanding which planetary systems are likely to have experienced violent migration events versus more gentle disk migration, astronomers can better assess the probability that these systems retained stable, habitable environments for rocky planets. This knowledge will become increasingly valuable as next-generation telescopes and missions seek to characterize the atmospheres of Earth-sized exoplanets and search for biosignatures—chemical indicators of life.

The study of hot Jupiters also informs our understanding of planetary system diversity more broadly. Every planetary system tells a story of formation, migration, and evolution shaped by initial conditions, chance encounters, and physical processes operating over millions to billions of years. By decoding the memories preserved in hot Jupiter orbits, we gain insight into the full range of possible outcomes when gas, dust, and gravity come together to form worlds around distant stars.

As this research demonstrates, even planets in the most extreme configurations can reveal secrets about their past through careful analysis of their present-day properties. The 30 hot Jupiters identified as likely disk-migration candidates serve as cosmic time capsules, preserving information about conditions in their planetary systems billions of years ago. Future observations and theoretical refinements will continue to extract these memories, bringing us ever closer to understanding the complex processes that shape planetary systems throughout our galaxy.

What new revelations about hot Jupiter formation will emerge in the coming years and decades? As observational capabilities advance and theoretical models grow more sophisticated, we can expect increasingly detailed insights into these fascinating worlds and the diverse pathways through which they arrived at their current extreme orbits. This is the essence of scientific discovery—each answer raising new questions, each mystery solved revealing deeper layers of cosmic complexity. As always, keep doing science and keep looking up!