In a groundbreaking discovery that reshapes our understanding of planetary evolution, astronomers have identified a cosmic missing link that reveals how the universe manufactures its most abundant type of planet. This finding bridges a critical gap in our knowledge of how planetary systems develop from their turbulent infancy into mature configurations, offering unprecedented insights into why our own Solar System appears to be such an unusual outlier in the galactic neighborhood.

The discovery centers on V1298 Tau, a remarkably young stellar system that serves as a planetary time capsule, capturing the dramatic transformation that most planetary systems undergo during their formative years. This system provides astronomers with a rare glimpse into the processes that create super-Earths and sub-Neptunes—the galaxy's most prevalent planetary types, which paradoxically are completely absent from our own Solar System. The research, conducted by an international collaboration led by scientists at the Astrobiology Center in Tokyo, represents a decade-long investigation into one of astronomy's most perplexing questions.

The Galactic Planetary Census: Understanding Cosmic Norms

When astronomers began discovering planets around other stars in the 1990s, they expected to find solar systems resembling our own. Instead, they encountered a universe dominated by a planetary class that doesn't exist in our cosmic backyard. Super-Earths—planets with masses between Earth and Neptune—and their slightly larger cousins, sub-Neptunes, orbit nearly every Sun-like star that scientists have examined with sufficient precision. These worlds, typically ranging from 1.5 to 4 times Earth's radius, occupy a size range conspicuously absent from our Solar System's planetary lineup.

According to data from NASA's Kepler Space Telescope and subsequent surveys, approximately 30-50% of Sun-like stars host at least one planet in this intermediate size range, making them statistically the most common planetary architecture in the Milky Way. Even more intriguingly, these worlds tend to orbit extremely close to their parent stars, completing their years in mere days or weeks—far closer than Mercury's 88-day orbit around our Sun. This prevalence raises a fundamental question: if these planets are so common throughout the galaxy, why did our Solar System develop along such a different evolutionary pathway?

Capturing Planetary Evolution in Real-Time

The V1298 Tau system, located approximately 350 light-years away in the constellation Taurus, offers a unique window into planetary adolescence. At just 20 million years old—a mere 0.4% the age of our 4.5-billion-year-old Solar System—this stellar nursery hosts four giant planets that are currently undergoing dramatic physical transformations. These worlds, each comparable in size to Neptune or Jupiter, represent what astronomers believe to be the precursor state of the compact super-Earths and sub-Neptunes found throughout the galaxy.

Lead researcher John Livingston from the Astrobiology Centre explains the significance: "We're essentially watching the universe's most successful planetary architecture in the making. This system shows us that the compact, intermediate-sized planets we see everywhere don't form directly in their current state—they evolve from much larger, puffier progenitors through a process of atmospheric loss and contraction."

Revolutionary Measurement Techniques

The research team faced a significant technical challenge: young stars like V1298 Tau are notoriously temperamental, exhibiting intense stellar activity that renders traditional planet-weighing methods ineffective. The standard technique, called radial velocity measurement, relies on detecting the subtle wobble a planet induces in its star's motion. However, young stars' surfaces roil with convection, spots, and flares that completely overwhelm these tiny planetary signals.

To circumvent this obstacle, the team employed an ingenious alternative approach utilizing Transit Timing Variations (TTVs). Over a ten-year observational campaign using facilities including the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) and various ground-based observatories, they meticulously recorded thousands of planetary transits—events when each planet passes in front of its star from our perspective, causing a slight dimming of the star's light.

The critical insight lies not in the transits themselves, but in their precise timing. When multiple planets orbit the same star, their mutual gravitational interactions create subtle perturbations in their orbits. These gravitational tugs cause planets to arrive at their transit points slightly early or late—sometimes by just a few minutes—compared to predictions based on a perfectly regular orbit. By analyzing these timing variations with sophisticated computational models, astronomers can calculate the planets' masses without needing to measure the star's wobble at all.

The Cosmic Cotton Candy: Unexpected Planetary Properties

The mass measurements revealed properties that surprised even veteran planet hunters. Despite their enormous sizes—ranging from 5 to 10 times Earth's radius—the planets weigh only 5 to 15 times Earth's mass. These figures translate to extraordinarily low densities, averaging around 0.1 to 0.3 grams per cubic centimeter—less dense than Saturn, and comparable to what planetary scientists playfully describe as "cosmic cotton candy."

To put this in perspective, Earth has a density of 5.5 grams per cubic centimeter, composed primarily of rock and metal. Neptune, despite being much larger, has a density of 1.6 grams per cubic centimeter due to its thick atmosphere of hydrogen, helium, and heavier volatiles surrounding a rocky core. The V1298 Tau planets are even puffier, indicating they possess enormously extended atmospheres that dwarf their relatively modest solid cores.

"These planets are in a state that standard formation models didn't predict. They're like cosmic balloons—mostly atmosphere with relatively small solid cores. Over the next billion years, they'll deflate dramatically as they lose much of this atmospheric envelope to space," explains Dr. Trevor David, a co-author from the Flatiron Institute's Center for Computational Astrophysics.

The Mechanism of Planetary Deflation

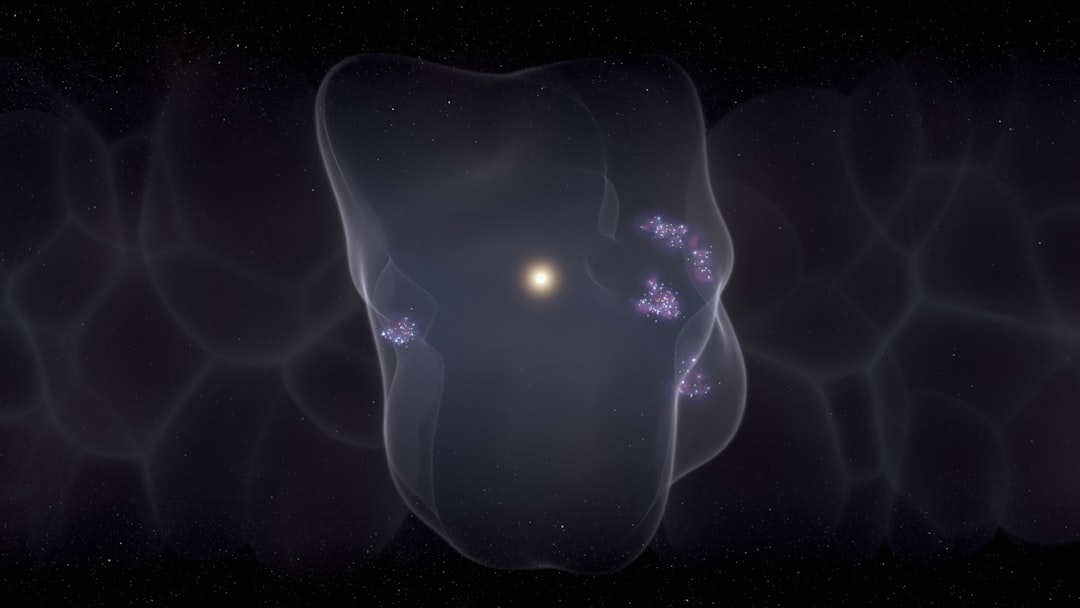

The extreme puffiness of these young planets provides crucial evidence for a theoretical process called atmospheric photoevaporation. When planets form within the gas-rich protoplanetary disk surrounding a young star, they can accumulate massive hydrogen and helium envelopes from the surrounding nebula. However, this pristine atmospheric reservoir doesn't last forever.

Young stars emit intense ultraviolet and X-ray radiation—far more energetic than our middle-aged Sun produces today. This high-energy radiation heats the upper atmospheres of nearby planets to thousands of degrees, giving atmospheric particles enough energy to escape the planet's gravity entirely. Additionally, when the protoplanetary disk dissipates—typically within the first 5-10 million years of a system's life—planets suddenly lose the atmospheric pressure support that helped them maintain their bloated configurations.

Research published in the Astrophysical Journal suggests that planets in this intermediate size range undergo a particularly dramatic transformation. Over hundreds of millions to billions of years, they can lose significant fractions of their initial atmospheric mass—in some cases, more than 50% of their original envelope. This process naturally explains how the puffy giants observed at V1298 Tau will eventually contract into the compact super-Earths and sub-Neptunes that dominate mature planetary systems.

Implications for Solar System Formation

The discovery raises profound questions about our own cosmic origins. If the V1298 Tau configuration represents the typical pathway for planetary system evolution, why does our Solar System lack any planets in the super-Earth/sub-Neptune size range? Several hypotheses attempt to explain this peculiarity:

- Timing of Giant Planet Formation: Jupiter and Saturn may have formed unusually early in our Solar System's history, creating gravitational barriers that prevented material from accumulating in the inner system to form super-Earths.

- Disk Dissipation Dynamics: The protoplanetary disk around the young Sun might have dispersed more rapidly than typical, limiting the time available for intermediate-mass planets to form close to the star.

- Migration History: Our giant planets may have undergone different migration patterns than those in typical systems, altering the distribution of solid material in the inner Solar System.

- Compositional Differences: The specific mix of elements and compounds in our protoplanetary disk might have favored the formation of either small rocky planets or large gas giants, with less material available in the intermediate range.

Understanding why our Solar System diverged from the galactic norm has important implications beyond pure curiosity. The prevalence of super-Earths and sub-Neptunes means that most potentially habitable planets in the galaxy likely fall into this size range rather than being Earth-sized worlds. Research from the NASA Exoplanet Science Institute suggests that understanding the atmospheric composition, climate dynamics, and potential habitability of these common worlds represents one of the most important challenges in astrobiology.

Future Observations and Unanswered Questions

The V1298 Tau discovery opens numerous avenues for future investigation. Astronomers plan to conduct follow-up observations using advanced facilities including the James Webb Space Telescope, which can analyze the atmospheric composition of these young planets through transmission spectroscopy—a technique that examines how starlight filters through a planet's atmosphere during transits.

Key questions that remain unanswered include:

- What is the exact composition of these extended atmospheres? Are they primarily hydrogen and helium, or do they contain significant amounts of water vapor, methane, or other compounds?

- How rapidly are these planets currently losing atmospheric mass, and how will this rate change as the star ages and its radiation output evolves?

- Do all super-Earths and sub-Neptunes in mature systems originate from deflated giants like those at V1298 Tau, or do some form through alternative pathways?

- What determines whether a planet retains enough atmosphere to remain a sub-Neptune versus losing most of its envelope to become a rocky super-Earth?

The research team plans to continue monitoring the V1298 Tau system for years to come, tracking how the planets' properties evolve in real-time. While the most dramatic changes occur over millions of years—too slow to observe directly—even subtle shifts in the planets' radii or atmospheric properties over decades could provide valuable constraints on theoretical models.

A Rosetta Stone for Planetary Science

Just as the famous Lucy fossil—discovered in Ethiopia in 1974—provided crucial evidence linking ancient apes to modern humans, the V1298 Tau system serves as a planetary Rosetta Stone, helping astronomers decipher the evolutionary history written in the demographics of mature planetary systems. This discovery demonstrates that the galaxy's most common planets aren't born in their current configurations but undergo dramatic metamorphoses during their formative years.

The finding also highlights the importance of studying planetary systems across a range of ages. Much of exoplanet science has focused on mature systems billions of years old, where planets have reached relatively stable configurations. However, understanding the dynamic processes that occur during planetary adolescence—the first few hundred million years—proves essential for building comprehensive theories of how planetary systems form and evolve.

As our census of exoplanetary systems continues to grow, with missions like TESS and future observatories identifying thousands more worlds, discoveries like V1298 Tau provide the crucial context needed to interpret this vast dataset. Each planetary system represents a single snapshot of a much longer evolutionary story, and only by studying systems at different ages can astronomers piece together the complete narrative of how the universe builds its planets.

This research reminds us that our Solar System, far from being the cosmic template, represents just one possible outcome among many evolutionary pathways. The universe's preferred planetary architecture looks quite different from our own familiar arrangement—and understanding why offers profound insights into the physical processes that shape planetary systems throughout the cosmos.