The dream of interstellar travel has captivated humanity for generations, but the harsh reality of physics has kept it firmly in the realm of science fiction. While chemical propulsion systems have successfully carried astronauts to the Moon and robotic probes throughout our Solar System, these conventional rockets are fundamentally inadequate for journeys to neighboring star systems. Even SpaceX's revolutionary Starship, capable of lifting unprecedented payloads into orbit, cannot approach the velocities necessary for practical interstellar missions. The solution to this challenge may lie in harnessing the most powerful energy source known to physics: antimatter.

A groundbreaking technical analysis by Casey Handmer, CEO of Terraform Industries, proposes an ambitious yet achievable pathway to developing antimatter propulsion technology within the constraints of existing spaceflight budgets. This comprehensive study, detailed in the Antimatter Development Program, argues that humanity stands at a technological threshold similar to the Manhattan Project's position in the 1940s—possessing the fundamental scientific knowledge but requiring focused engineering development to transform theory into reality.

Understanding Antimatter's Unprecedented Energy Density

The physics underlying antimatter propulsion is elegantly simple yet staggeringly powerful. When antimatter particles encounter their ordinary matter counterparts, they undergo complete annihilation, converting 100% of their combined mass directly into energy according to Einstein's famous equation E=mc². The critical factor here is that c² term—representing the speed of light squared—which equals approximately 9 × 10¹⁷ meters squared per second squared, an almost incomprehensibly large multiplier.

To put this in perspective, antimatter releases roughly 1,000 times more energy per kilogram than nuclear fission reactions, which currently represent our most powerful practical energy source. Chemical combustion, the technology powering every rocket that has ever flown to space, produces merely one ten-billionth the energy density of antimatter annihilation. This dramatic difference in energy release is what makes antimatter theoretically capable of propelling spacecraft to significant fractions of light speed—velocities that would reduce interstellar journey times from millennia to mere decades.

"The energy density advantage of antimatter isn't just incremental—it's transformational. We're talking about the difference between crawling and flying when it comes to exploring our cosmic neighborhood," explains Dr. Gerald Jackson, former physicist at Fermilab and founder of Hbar Technologies.

Three Critical Engineering Challenges

While the theoretical physics of antimatter propulsion is well understood, translating this knowledge into functional spacecraft systems requires overcoming three formidable technical obstacles: production efficiency, reliable storage mechanisms, and practical engine designs. Each challenge represents a significant engineering undertaking, yet none appears insurmountable given focused research and development efforts.

Antimatter Production: From Laboratory Curiosity to Industrial Scale

Current antimatter production capabilities at facilities like CERN's Antiproton Decelerator manage to create thousands of antimatter atoms daily—a remarkable achievement that would have seemed impossible just two decades ago. However, this production rate remains woefully inadequate for propulsion applications, analogous to the minuscule plutonium production capacity available in the early 1940s before the Manhattan Project's industrial-scale facilities came online.

The fundamental challenge lies in the extraordinary inefficiency of current production methods, which convert only about 0.000001 percent of input energy into stored antimatter. This process requires massive particle accelerators and sophisticated vacuum storage rings, making it extraordinarily expensive—currently estimated at approximately $62.5 trillion per gram of antihydrogen. However, recent experimental demonstrations have achieved efficiency improvements of eight-fold or more, suggesting that continued research could yield the exponential gains necessary for practical applications.

The key insight from Handmer's analysis is that interstellar missions don't necessarily require antimatter to become cheap in absolute terms—they only need it to become cheaper than the alternatives. For deep space missions where every additional meter per second of velocity is invaluable, even antimatter costing billions of dollars per gram might prove economically justifiable if it enables missions that would otherwise be impossible.

Storage Solutions: Containing the Most Volatile Substance Imaginable

If production represents a daunting challenge, antimatter storage may be even more formidable. The fundamental problem is straightforward: antimatter annihilates instantly upon contact with any ordinary matter, releasing its energy in a burst of gamma rays and charged particles. This makes traditional containment vessels—tanks, bottles, or any physical container—completely impractical.

Current storage systems employ electromagnetic Penning traps, which use carefully configured magnetic and electric fields to suspend charged antimatter particles in ultra-high vacuum environments. These systems have successfully stored antiprotons for over a year at CERN, demonstrating that long-term containment is theoretically possible. However, existing storage rings are massive, delicate, and require continuous power input—hardly ideal characteristics for spacecraft systems that must operate reliably for years or decades.

A more promising approach involves electrostatic containment of neutral antihydrogen atoms in cryogenically cooled vacuum chambers. This technology, which bears similarities to systems already employed in quantum computing applications, would hold tiny crystals or droplets of antihydrogen suspended by precisely controlled electric fields at temperatures approaching absolute zero. Intriguingly, this technology could be tested and refined using ordinary hydrogen simply by inverting the charge configuration, allowing safe development without the extraordinary costs and risks associated with antimatter handling.

Engine Design: Harnessing Annihilation for Thrust

Even with adequate antimatter supplies and reliable storage, the final challenge lies in designing propulsion systems that can safely and efficiently convert annihilation energy into useful thrust. Several conceptual approaches exist, each offering different performance characteristics suited to specific mission profiles.

The simplest design concept uses antimatter to heat a solid-core thermal rocket, where antiproton annihilation heats a refractory block through which conventional propellant flows. This approach, similar in principle to nuclear thermal rockets studied by NASA's nuclear propulsion programs, could achieve specific impulses of 1,000-2,000 seconds—roughly double that of chemical rockets—without requiring the massive reactor assemblies needed for nuclear systems.

More sophisticated designs leverage a clever synergy between antimatter and uranium-238, the naturally occurring isotope that comprises 99.3% of natural uranium. When antiprotons strike U-238 nuclei, they can trigger fission reactions, producing highly charged fission fragments that deposit their energy far more efficiently into the exhaust stream than gamma rays alone. This antimatter-catalyzed nuclear propulsion concept could achieve specific impulses ranging from 2,000 seconds for high-thrust applications up to 50,000 seconds or more for interstellar missions where maximizing velocity matters more than acceleration rate.

Mission Requirements: Surprisingly Modest Quantities

Perhaps the most encouraging finding from Handmer's analysis is that practical deep space missions require surprisingly modest antimatter quantities. A mission to Pluto and back in under 20 years—dramatically faster than the nearly decade-long one-way journey of NASA's New Horizons probe—would need just 45 grams of antimatter combined with approximately 10 kilograms of uranium-238. The entire fuel assembly would occupy roughly 500 cubic centimeters, about the volume of a large coffee mug.

For context, this represents less antimatter than humanity's total historical production to date, yet it would enable a mission profile impossible with any other known propulsion technology. More ambitious interstellar missions to nearby stars like Proxima Centauri would require larger quantities—perhaps several kilograms—but still within the realm of industrial-scale production if sufficient resources were committed to the effort.

The Path Forward: A Modern Manhattan Project

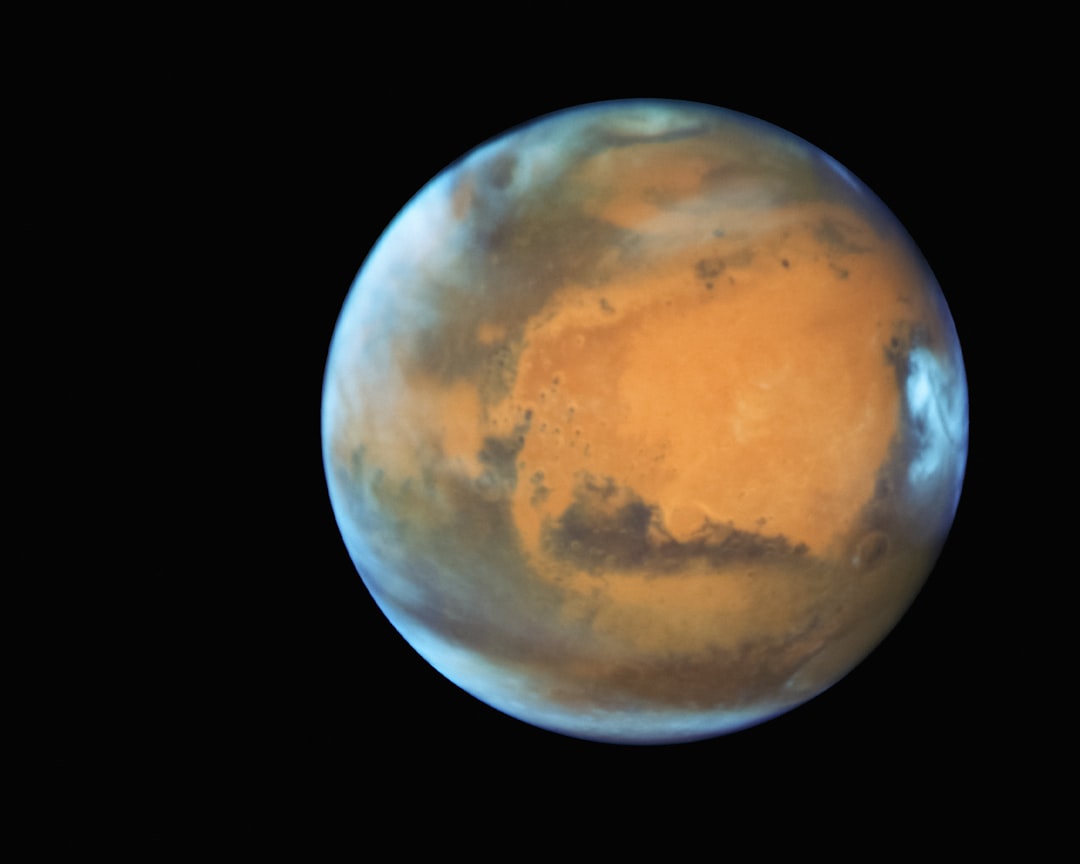

The case for a coordinated antimatter development program rests on a simple observation: with chemical propulsion largely solved through reusable rockets like SpaceX's Starship and Falcon 9, antimatter represents the logical next frontier for expanding humanity's reach into deep space. The technical challenges, while formidable, appear surmountable given focused effort comparable to historical programs like the Manhattan Project or Apollo Program.

Key milestones for such a program would include:

- Production efficiency improvements: Achieving at least three orders of magnitude improvement in antimatter production efficiency through advanced accelerator designs and optimized particle capture systems

- Storage technology demonstration: Developing and testing compact, robust antimatter storage systems capable of safely containing gram-quantities for mission-duration timescales

- Engine prototype development: Building and testing antimatter thermal and antimatter-catalyzed nuclear engines at scales sufficient to validate performance models

- Mission architecture studies: Detailed engineering analysis of complete spacecraft systems for specific high-value missions like rapid Kuiper Belt exploration or interstellar precursor missions

- Safety protocols and infrastructure: Establishing comprehensive safety procedures and ground-based infrastructure for antimatter production, handling, and spacecraft fueling operations

Implications for Humanity's Future in Space

The development of practical antimatter propulsion would fundamentally transform humanity's relationship with space exploration. Missions currently requiring decades could be accomplished in years. The outer Solar System, currently a remote frontier accessible only to robotic probes after multi-year journeys, could become as accessible as the Moon was during the Apollo era. Perhaps most significantly, interstellar precursor missions reaching several percent of light speed could return data from the gravitational focus of our Sun—a natural telescope of extraordinary power—or even reach the nearest stars within a human lifetime.

The economic implications are equally profound. While initial development costs would certainly reach tens or hundreds of billions of dollars, the resulting capability would open entirely new categories of scientific investigation and potentially economic exploitation. Access to the outer Solar System's vast resources of water ice, rare isotopes, and pristine materials could prove transformational for both Earth-based and space-based industries.

Moreover, antimatter propulsion development would drive advances in numerous related technologies: particle physics, superconducting magnets, cryogenic systems, advanced materials, and precision electromagnetic control systems. These spinoff technologies, much like those from the Apollo Program, could generate economic benefits far exceeding the direct costs of the development program itself.

As humanity stands on the threshold of becoming a truly spacefaring civilization, with reusable rockets making Earth orbit routine and plans for lunar bases and Mars settlements advancing, the question is not whether we can develop antimatter propulsion, but whether we have the vision and commitment to pursue it. The physics is sound, the engineering challenges are daunting but not insurmountable, and the potential rewards—both scientific and practical—are immense. The case for an antimatter Manhattan Project is clear: the stars are waiting, and we now possess the knowledge to reach them.