Our understanding of the cosmos has long been shaped by detailed observations of our own star, the Sun. For centuries, astronomers have meticulously studied solar behavior, documenting everything from sunspot cycles to explosive solar flares that occasionally disrupt our planet's magnetic field. This intimate knowledge of our stellar neighbor has naturally led scientists to assume that other main sequence stars throughout the galaxy operate according to similar principles. However, groundbreaking new research involving observations of more than 14,000 stars has revealed a startling truth: when it comes to the relationship between stellar activity and flare production, our Sun is remarkably unusual.

A comprehensive study utilizing data from NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) has uncovered a fundamental disconnect in how most stars produce their dramatic energy outbursts. While solar flares on our Sun consistently appear in regions marked by sunspots—those darker, cooler areas caused by intense magnetic field concentrations—the same correlation mysteriously fails to hold true for the vast majority of other stars. This discovery, detailed in a recent arXiv preprint by Zhang and colleagues, challenges decades of assumptions about stellar magnetic dynamics and raises profound questions about what makes our Sun's behavior so distinctive in the cosmic landscape.

The Sun as Our Stellar Rosetta Stone

The Sun holds a privileged position in astrophysics not merely because it sustains life on Earth, but because its proximity—a mere 93 million miles away—allows us to study stellar processes with unparalleled detail. Over the past four centuries of telescopic observations, astronomers have documented the Sun's dynamic nature with extraordinary precision. We've learned that our star undergoes regular activity cycles lasting approximately 11 years, during which the number and distribution of sunspots waxes and wanes in a predictable pattern. These cycles directly correlate with increased magnetic activity and a higher frequency of solar flares—violent eruptions that can release as much energy as billions of nuclear bombs in a matter of minutes.

Beyond these short-term variations, scientists at NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory have revealed that the Sun has gradually brightened over geological timescales, increasing its luminosity by approximately 30% since the formation of our solar system 4.6 billion years ago. This long-term evolution, combined with the Sun's cyclical behavior, has provided the foundational framework for understanding how all main sequence stars—those in the stable, hydrogen-burning phase of stellar evolution—should behave throughout the galaxy.

Extending Solar Physics to the Stellar Realm

The natural extension of solar physics to other stars has proven both successful and challenging. Like our Sun, other stars exhibit starspots—magnetically active regions that appear darker than their surroundings due to locally suppressed convection and reduced temperatures. These features, analogous to sunspots, serve as visible markers of a star's magnetic field strength and complexity. However, observing starspots on distant stars presents formidable technical challenges. Unlike the Sun, where individual spots can be tracked across the solar disk, distant stars appear as mere points of light even through the most powerful telescopes.

Despite these observational hurdles, astronomers have successfully mapped starspot activity on approximately 400 stars using sophisticated techniques such as Doppler imaging and long-term photometric monitoring. These studies, conducted by facilities including the European Southern Observatory, have revealed that stellar activity cycles are indeed widespread, though their periods vary considerably—ranging from as brief as 3 years to as long as 20 years depending on the star's mass, rotation rate, and age. Spectroscopic analysis of these stars confirms that their magnetic field variations follow similar cyclical patterns, strengthening and weakening in concert with starspot numbers.

The Expected Connection Between Spots and Flares

Given that stellar magnetic fields are the fundamental drivers of both starspots and flares, conventional wisdom dictated that these phenomena should be intimately connected across all stars. On the Sun, this relationship is remarkably clear: solar flares predominantly occur in active regions marked by complex sunspot groups. The magnetic field lines in these areas become twisted and stressed by the Sun's differential rotation and convective motions, eventually releasing their pent-up energy through magnetic reconnection—the same process that powers Earth's auroras, albeit on a vastly more energetic scale.

"For decades, we've operated under the assumption that what we observe on the Sun represents universal stellar behavior. The discovery that stellar flares and starspots are generally uncorrelated fundamentally challenges this paradigm and suggests we've been missing something crucial about how magnetic fields operate in different stellar environments."

Revolutionary Findings from TESS Observations

The breakthrough came from an innovative analysis of data collected by the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, a NASA mission launched in 2018 primarily to discover planets orbiting nearby stars. While TESS was designed for planet hunting, its continuous, high-precision monitoring of stellar brightness makes it an exceptional tool for studying stellar variability. The research team, led by Andy B. Zhang, developed a clever indirect method to correlate starspot coverage with flare activity across thousands of stars simultaneously.

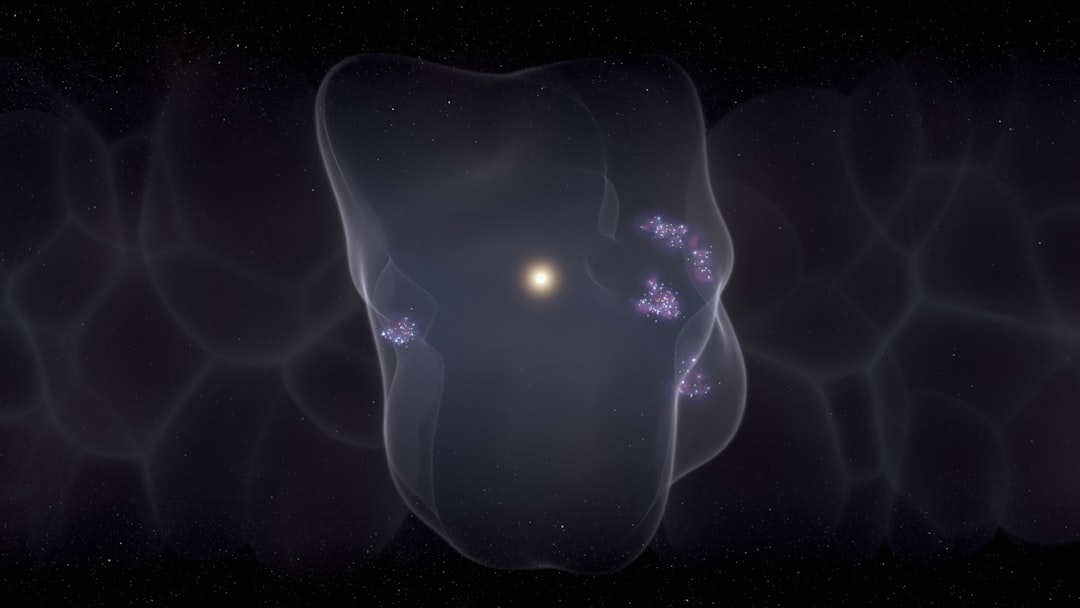

The technique exploits a simple principle: when a star is covered with numerous starspots, it appears slightly dimmer when those spots rotate into our line of sight compared to when they face away from us. As the star rotates, this creates a periodic brightness variation that reveals both the rotation period and the relative coverage of dark spots. Simultaneously, stellar flares appear as sudden, brief spikes in brightness lasting from minutes to hours. Since we can only observe flares occurring on the hemisphere of the star facing Earth, the team could determine whether flares preferentially occur when starspots are visible—exactly as they do on the Sun.

Unprecedented Scale and Surprising Results

The scale of this investigation was truly remarkable. Analyzing photometric data from more than 14,000 stars, the researchers identified and catalogued over 200,000 individual stellar flares. This massive dataset provided the statistical power necessary to detect even subtle correlations between flare occurrence and starspot visibility. The team employed sophisticated algorithms to distinguish genuine flares from other sources of brightness variation, including instrumental artifacts and cosmic ray impacts on the detector.

The results were startling. While solar observations consistently show that flares and sunspots occur together—with correlation coefficients approaching unity—the stellar data revealed something entirely different. For the thousands of stars in the sample, flares and starspots showed essentially no correlation. When a stellar flare occurred, the probability that starspots were facing Earth was approximately 50%—no better than random chance. This finding held true across stars of different masses, ages, and activity levels, suggesting a fundamental difference in how magnetic energy is stored and released on most stars compared to our Sun.

Implications for Stellar Physics and Solar Uniqueness

This discovery has profound implications for our understanding of stellar magnetic dynamics. The tight correlation between sunspots and solar flares has been a cornerstone of solar physics for decades, forming the basis for space weather prediction models and our understanding of the solar cycle's impact on Earth. If this relationship doesn't hold for most other stars, it suggests that either the Sun's magnetic field configuration is unusual, or the mechanisms triggering flares operate differently depending on stellar properties we haven't yet identified.

Several hypotheses might explain this discrepancy. One possibility is that the Sun's relatively slow rotation rate and the specific structure of its convective zone create magnetic field geometries that naturally concentrate flare activity in visible starspot regions. Faster-rotating stars, which comprise a significant fraction of the sample, might generate more globally distributed magnetic fields where flares can occur anywhere on the stellar surface, regardless of starspot locations. Alternatively, the depth and complexity of subsurface magnetic flux emergence might differ substantially between the Sun and other stars, affecting where and when magnetic energy is released.

Questions About Solar-Stellar Connection

The research also raises intriguing questions about whether we can reliably use the Sun as a template for understanding other stars. For decades, the field of solar-stellar physics has operated on the principle that detailed solar observations can illuminate processes occurring on stars too distant for similar scrutiny. While this approach has yielded valuable insights into stellar rotation, magnetic cycles, and atmospheric structure, the new findings suggest we must be cautious about assuming solar-like behavior extends to all stellar phenomena.

- Magnetic Field Topology: The Sun's dipolar magnetic field configuration may be atypical, with other stars exhibiting more complex multipolar geometries that distribute flare activity differently across their surfaces

- Convective Zone Differences: Variations in the depth and vigor of stellar convection zones could fundamentally alter how magnetic fields are generated and organized, affecting the spatial relationship between spots and flares

- Rotation Rate Effects: The Sun's 25-day equatorial rotation period places it in a specific regime of stellar rotation; faster or slower rotators might exhibit qualitatively different magnetic behavior

- Observational Selection Effects: While the study controlled for many biases, subtle effects related to stellar inclination, activity level, or spot distribution patterns might still influence the observed correlations

Future Directions and Unanswered Questions

This groundbreaking work opens numerous avenues for future investigation. Understanding why the Sun exhibits such a strong spot-flare correlation while other stars do not could revolutionize our knowledge of stellar magnetism and potentially improve our ability to predict solar activity. Future missions, including the ESA's Solar Orbiter, will provide unprecedented views of the Sun's polar regions and subsurface dynamics, potentially revealing the key factors that make solar magnetic behavior distinctive.

Additionally, next-generation space telescopes with enhanced time resolution and sensitivity will enable even more detailed studies of stellar flares and rotational modulation. The upcoming PLATO mission, scheduled for launch in the late 2020s, will monitor hundreds of thousands of stars with the precision necessary to detect subtle patterns in flare occurrence and starspot evolution. Combined with advanced numerical simulations of stellar magnetic fields—a field being advanced by supercomputing facilities worldwide—these observations promise to unravel the mystery of why our Sun's flare behavior appears so unusual in the broader stellar context.

Perhaps most intriguingly, this research highlights how much we still have to learn about our own star despite centuries of intensive study. The Sun may be our closest and most familiar stellar neighbor, but it continues to surprise us, reminding us that each star in the galaxy may have its own unique story to tell about the complex interplay between rotation, convection, and magnetism that shapes stellar evolution and activity.