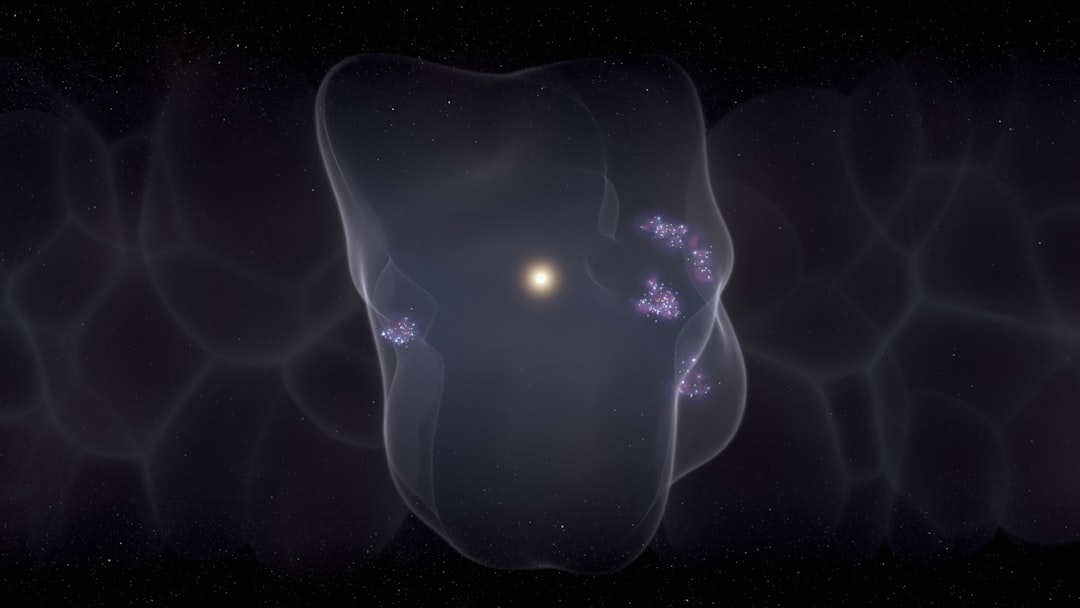

In the vast stellar nurseries of our galaxy, young protostars are actively sculpting their cosmic environments long before they ignite the nuclear fusion that will power them for billions of years. New observations from the Hubble Space Telescope are revealing the dramatic ways these embryonic stars reshape the dense molecular clouds from which they emerge, offering unprecedented insights into the violent and beautiful process of stellar birth.

These remarkable images focus on three protostars embedded within the Orion Molecular Cloud complex (OMC), one of the most prolific star-forming regions within our cosmic neighborhood, located approximately 1,350 light-years from Earth. The observations are helping astrophysicists understand the complex feedback mechanisms through which nascent stars interact with their surroundings, carving out massive cavities and bubbles in the surrounding gas through powerful jets and stellar winds. This research represents a crucial step forward in understanding how stars like our Sun came to be, and how they influenced their birth environments during their formative years.

The Extended Adolescence of Stellar Formation

Unlike the instantaneous spark suggested by popular imagination, the formation of a star is an extended process that unfolds over hundreds of thousands to millions of years. During the protostellar phase, these cosmic infants are still actively accumulating mass from the surrounding molecular cloud, growing steadily toward their eventual main-sequence configuration. This prolonged period of growth occurs long before the core temperatures and pressures reach the critical threshold necessary to initiate hydrogen fusion—the hallmark of a mature, main-sequence star.

The protostellar phase is characterized by intense activity despite the absence of nuclear fusion. Material from the surrounding molecular cloud first accumulates into a rotating disk around the young star, known as a protoplanetary disk or accretion disk. Through processes that scientists are still working to fully understand, gas and dust from this disk gradually spiral inward, adding to the star's growing mass. However, this accretion process is far from perfectly efficient—a significant portion of the infalling material is redirected and expelled from the system entirely.

Powerful Outflows Reshape Cosmic Landscapes

Among the most spectacular features of protostars are their bipolar jets—highly collimated streams of material ejected at velocities that can reach hundreds of kilometers per second. These jets are primarily composed of ionized hydrogen, channeled along the protostar's powerful magnetic field lines and expelled from the stellar poles. The mechanism behind these jets involves a complex interplay between the star's rotation, its magnetic field, and the infalling material from the accretion disk.

One of the newly released Hubble images showcases HOPS 181, a young protostar deeply embedded within layers of obscuring gas and dust. The image reveals a distinctive curved arc in the upper left portion of the frame—a structure sculpted by the protostar's powerful outflows. This arc represents the boundary where the high-velocity jets collide with the surrounding molecular cloud material, compressing and heating it until it glows in visible light. Such Herbig-Haro objects, named after the astronomers who first studied them, serve as cosmic laboratories for understanding shock physics and gas dynamics.

"These observations demonstrate that even before nuclear fusion begins, protostars are already powerful agents of change in their environments, fundamentally altering the gas reservoirs from which future generations of stars will form," explains research from the Space Telescope Science Institute.

The Dual Nature of Protostellar Outflows

In addition to the focused polar jets, protostars generate wide-angle stellar winds that flow outward in all directions from the stellar surface. These winds differ dramatically from the relatively gentle solar wind we observe from our mature Sun. Protostellar winds can be orders of magnitude more powerful, carrying away significant amounts of material and energy. The combination of focused jets and wide-angle winds creates a complex three-dimensional structure around young stars, clearing out cavities and channels in the surrounding molecular cloud.

The strength of these outflows varies dramatically over the protostar's development. Young stars can experience episodic periods of enhanced accretion and corresponding increases in outflow intensity—events that manifest as dramatic brightening episodes. Over time, as the protostar exhausts its reservoir of infalling material and approaches the main sequence, both the accretion rate and the intensity of the outflows gradually diminish.

Investigating HOPS 310 and Cavity Formation

Another striking image from this Hubble survey reveals the environment around HOPS 310, though the protostar itself remains hidden behind dense veils of gas and dust. The most prominent object in the image is CVSO 188, a bright foreground star whose distinctive diffraction spikes make it immediately recognizable. However, the scientifically significant object lies to the left of center—HOPS 310, betrayed by the glowing cavity walls it has carved into the surrounding medium.

One of HOPS 310's jets is clearly visible as an elongated stream of material extending toward the upper right of the image. This jet represents material being ejected at high velocity, plowing through the ambient molecular cloud and creating a tunnel of cleared space. The bright walls of the cavity represent regions where the jet material collides with the surrounding gas, creating shock fronts that heat and ionize the material, causing it to emit visible light.

Unexpected Findings About Cavity Evolution

One of the most significant findings from this research challenges previous assumptions about how these cavities evolve over time. Scientists discovered that the cavities did not grow substantially larger as the protostars progressed through later stages of formation. This observation is somewhat counterintuitive—one might expect that as protostars continue to inject energy into their surroundings, the cavities would steadily expand.

The research team also examined whether changes in the star formation rate (SFR) within the Orion Molecular Cloud complex could be attributed to this cavity-carving process. They found that while both the mass accretion rates of individual protostars and the overall star formation rate in the OMC have decreased over time, these trends cannot be directly attributed to the mechanical feedback from jets and winds. This suggests that other factors—perhaps the depletion of the available gas reservoir or large-scale dynamics within the molecular cloud—play more significant roles in regulating star formation than previously thought.

The Orion Molecular Cloud: A Stellar Nursery in Our Backyard

The Orion Molecular Cloud complex represents one of the most intensively studied star-forming regions in modern astronomy, and for good reason. Its relative proximity to Earth—a mere 1,350 light-years, practically next door on cosmic scales—combined with its high level of ongoing star formation makes it an ideal laboratory for studying stellar birth. The complex contains thousands of stars in various stages of formation, though many remain hidden within their cocoons of gas and dust, detectable only through infrared and radio observations.

The OMC includes several well-known features visible even to amateur astronomers, including the Orion Nebula (M42), one of the brightest nebulae in the night sky. The three stars forming Orion's Belt serve as easily recognizable landmarks, while the red supergiant Betelgeuse marks one corner of the constellation. The red crescent shape of Barnard's Loop, an enormous emission nebula, arcs across the region—itself a remnant of ancient stellar winds and supernovae that have shaped this region over millions of years.

Connecting the Past to the Present: Our Sun's Origins

These observations of protostars in the Orion Molecular Cloud offer a window into our own star's distant past. Approximately 4.6 billion years ago, our Sun formed within a similar molecular cloud, likely surrounded by hundreds or thousands of sibling stars. Like the protostars observed by Hubble, the young Sun would have generated powerful jets and stellar winds, carving out its own cavity within the natal cloud and shaping the disk of material that would eventually coalesce into the planets, asteroids, and comets of our solar system.

The third Hubble image in this series beautifully captures the edge of a cavernous cavity, with its boundary clearly visible in the upper left portion of the frame. The cavity has been excavated by stellar winds from a bright protostar located to the right of the cleared region. Background stars glitter throughout the upper right of the image, providing a reminder of the countless other stellar systems scattered throughout our galaxy.

The Future of These Stellar Nurseries

Over the coming millions of years, the protostars currently embedded within the Orion Molecular Cloud will complete their journey to the main sequence, settling into stable configurations where nuclear fusion balances gravitational collapse. The molecular cloud itself will gradually disperse, blown away by the combined stellar winds of the newly formed stars and disrupted by the shock waves from supernovae as the most massive stars reach the ends of their lives.

Eventually, little evidence will remain of the dense molecular cloud that once filled this region. The stars born together will drift apart, their mutual gravitational bonds too weak to hold them together against the tidal forces of the galaxy. They will become solitary wanderers like our Sun, carrying with them any planets and planetary systems that formed from the remnants of their accretion disks. Some may retain faint chemical or kinematic signatures of their common origin, allowing missions like ESA's Gaia to identify them as members of the same stellar family, even after billions of years of separation.

Implications for Understanding Star Formation

These Hubble observations contribute to a growing body of evidence about the complex interplay between protostars and their environments. The research highlights several key insights:

- Feedback Complexity: The mechanical feedback from protostellar jets and winds is more nuanced than simple models suggest, with cavity sizes not directly correlating with stellar age or evolutionary stage

- Energy Distribution: Even without nuclear fusion, protostars inject substantial energy into their surroundings through kinetic energy in jets and winds, fundamentally altering the structure of molecular clouds

- Star Formation Regulation: While jets and winds clearly affect local conditions, they may not be the primary factors regulating star formation rates on larger scales within molecular clouds

- Magnetic Field Importance: The collimation of jets along magnetic field lines underscores the crucial role of magnetic fields in channeling and directing outflows from young stars

- Observational Techniques: The ability to observe protostars across multiple wavelengths, from visible light to infrared and radio, provides complementary information about different aspects of the star formation process

Future observations with next-generation facilities, including the James Webb Space Telescope and ground-based instruments like the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), will continue to refine our understanding of these processes. Webb's infrared capabilities are particularly valuable for penetrating the dusty cocoons surrounding protostars, while ALMA's sensitivity to molecular emission lines provides detailed information about gas kinematics and chemistry.

As we continue to study stellar nurseries like the Orion Molecular Cloud, we gain not only scientific knowledge but also a deeper appreciation for the cosmic processes that led to our own existence. Every star, every planet, and ultimately every atom in our bodies was forged through processes like those captured in these stunning Hubble images—a reminder of our profound connection to the cosmos and the ongoing cycle of stellar birth, life, and death that shapes our universe.