In a groundbreaking proposal that could revolutionize our understanding of planetary formation beyond our solar system, researchers have outlined an ambitious strategy to intercept and study visitors from distant stellar neighborhoods. The European Space Agency's Comet Interceptor mission, scheduled for launch in 2029, may serve as the blueprint for humanity's first close encounter with an interstellar object (ISO)—a cosmic wanderer that originated in an alien solar system light-years away from our own.

A comprehensive white paper submitted to the UK Space Frontiers 2035 prioritization exercise details how this innovative "wait in space" approach could enable scientists to study pristine material from other planetary systems. Led by Colin Snodgrass from the Institute for Astronomy at the University of Edinburgh, the research team argues that intercepting an interstellar comet like 3I/ATLAS represents one of humanity's most realistic opportunities to directly sample matter from beyond our solar system—a feat that would have seemed impossible just a decade ago.

The proposal comes at a pivotal moment in astronomy. With the recent discoveries of 1I/'Oumuamua in 2017 and 2I/Borisov in 2019, scientists have confirmed what they long suspected: interstellar objects regularly pass through our cosmic neighborhood, offering fleeting opportunities to study the building blocks of distant planetary systems. The challenge lies in detecting these visitors early enough and having the technology ready to intercept them during their brief sojourn through the inner solar system.

The Evolution of Comet Exploration: From Flyby to Interception

The history of comet exploration provides crucial context for understanding why the Comet Interceptor mission represents such a paradigm shift. Humanity's first attempt to study a comet up close occurred in September 1985, when NASA's International Cometary Explorer (ICE) passed through the tail of comet Giacobini-Zinner. Despite lacking cameras, this pioneering mission successfully measured the magnetic field and plasma environment of a comet for the first time.

Subsequent missions dramatically advanced our understanding of these primordial time capsules. The 1999 Stardust mission achieved a historic milestone by returning the first samples from a comet to Earth in 2006, delivering thousands of dust grains that revealed surprising complexity in cometary composition. NASA's Deep Impact mission in 2005 took a more aggressive approach, deliberately smashing a copper impactor into comet Tempel 1 to excavate subsurface material and analyze its composition.

Perhaps most transformative was the European Space Agency's Rosetta mission, which spent two years accompanying comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko through its journey around the Sun. Rosetta's lander, Philae, achieved the first-ever soft landing on a comet nucleus, while the orbiter captured stunning images of jets erupting from the surface and detected complex organic molecules including the amino acid glycine—a fundamental building block of proteins.

"The next step beyond the detailed investigation of a relatively pristine remnant from our own Solar System's protoplanetary disc will be to compare this with a body that formed elsewhere, to investigate the commonalities and differences between the planet formation process in different places and times in the galaxy."

Why Interstellar Objects Demand a Revolutionary Approach

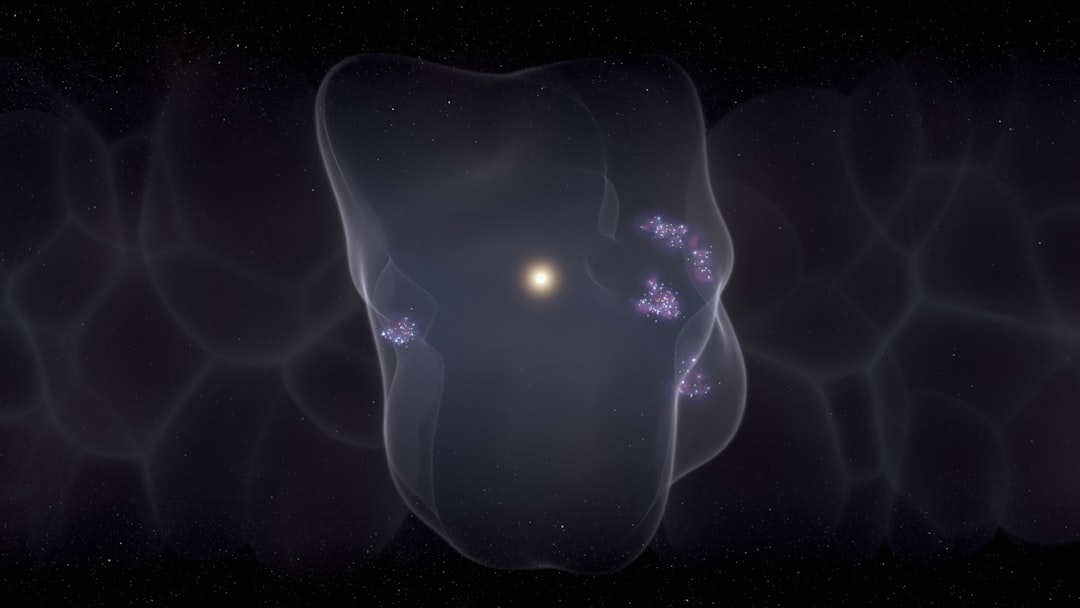

The Comet Interceptor mission fundamentally differs from all previous comet missions in one critical aspect: it will launch before its target is identified. This spacecraft will be parked at the Sun-Earth Lagrange Point 2 (L2), approximately 1.5 million kilometers from Earth, where it will remain dormant until astronomers detect a suitable target—either a dynamically new long-period comet entering the inner solar system for the first time, or potentially an interstellar visitor.

This "wait in space" architecture proves essential for intercepting ISOs because these objects provide virtually no advance warning. Unlike comets native to our solar system, which follow predictable orbits that can be calculated years or even decades in advance, interstellar objects appear suddenly and disappear just as quickly. By the time astronomers detect an ISO and calculate its trajectory, a conventional mission would have insufficient time to design, build, launch, and navigate a spacecraft to intercept it.

Previous proposals for chasing known ISOs like 'Oumuamua or Borisov have proven impractical for multiple reasons. Such missions would require untested propulsion systems, including potentially solar sails or nuclear propulsion, to achieve the extreme velocities necessary to catch up with these rapidly departing objects. Furthermore, these proposals face severe communication challenges—by the time a spacecraft reached its target, it could be 100 astronomical units (AU) or more from Earth, making data transmission extremely difficult and time-consuming.

The Scientific Case: What Makes Interstellar Comets So Valuable

The scientific motivation for studying interstellar objects extends far beyond mere curiosity about our cosmic neighbors. Recent exoplanet discoveries have revealed that our solar system may be something of an outlier in galactic terms. The most common type of exoplanet detected—sub-Neptunes with masses between Earth and Neptune—is completely absent from our solar system. Meanwhile, many exoplanetary systems contain "hot Jupiters"—massive gas giants orbiting extremely close to their host stars—a configuration not found in our more orderly arrangement.

Understanding why these differences exist requires studying the planet formation process in other stellar systems. Comets and asteroids serve as archaeological records of planetary birth, preserving material from the protoplanetary disk in which planets coalesced. Because comets spend most of their existence in the frigid outer reaches of their stellar systems, their icy interiors remain largely unaltered, maintaining a chemical and isotopic record of conditions during the earliest phases of system formation.

According to current models of planetary system evolution, the process of planet formation naturally ejects vast numbers of small icy bodies. As planets migrate inward or outward due to gravitational interactions, they scatter countless comets and asteroids, some of which achieve sufficient velocity to escape their home system entirely. These interstellar wanderers then drift through the galaxy for millions or billions of years until chance brings them near another star—like our Sun.

Comparative Planetology Across the Galaxy

The composition of interstellar objects should vary depending on their source region within the galaxy. Systems that formed in the metal-rich inner galaxy may produce comets with different compositions than those from metal-poor outer regions. Similarly, comets ejected from systems around different types of stars—from massive O-type stars to small M-dwarfs—might reflect variations in the protoplanetary disk chemistry associated with different stellar environments.

As the white paper authors explain, ISOs present a unique opportunity to conduct comparative planetology on an interstellar scale. By analyzing the composition, structure, and physical properties of comets from other systems, scientists can test theories about planet formation under different conditions and at different epochs in galactic history. This data would be impossible to obtain through any other means, as even our most powerful telescopes cannot resolve individual comets in distant planetary systems.

Mission Architecture: Adapting Comet Interceptor for Interstellar Targets

The proposed interstellar object mission would closely follow the Comet Interceptor design philosophy, with some crucial modifications. The baseline CI mission consists of a primary spacecraft and two smaller sub-probes that would separate before the comet encounter, allowing simultaneous observations from multiple vantage points. This multi-spacecraft approach provides 3D spatial information about the comet's structure and activity that would be impossible to obtain from a single flyby trajectory.

For an ISO mission, the payload requirements remain largely similar to those of the standard Comet Interceptor. High-resolution imaging systems would reveal the bulk structure and surface features of the nucleus, including evidence for impact craters, layering, or surface processing by cometary activity. These morphological characteristics provide critical clues about the object's formation environment and subsequent evolution. Infrared and ultraviolet spectrometers would analyze the composition of gases and dust released by the comet, while magnetometers and plasma instruments would characterize its interaction with the solar wind.

However, one significant addition stands out: a neutral mass spectrometer becomes crucial for an interstellar comet mission. This instrument would provide detailed measurements of the molecular composition of gases released from the nucleus, including the isotopic ratios of key elements like hydrogen, carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen. These isotopic signatures serve as fingerprints of the comet's formation environment and could reveal whether it originated in a stellar system with a different chemical makeup than our own.

The Economics of Interstellar Exploration

One of the most appealing aspects of the Comet Interceptor approach is its cost-effectiveness. Designed as a relatively modest mission, CI will launch as a secondary payload alongside the ESA's Ariel exoplanet characterization mission, significantly reducing launch costs. This "rideshare" approach demonstrates that groundbreaking science doesn't necessarily require billion-dollar flagship missions.

An interstellar object interceptor could follow the same model, launching as a secondary payload and waiting in space for years if necessary. The authors argue that this patience-based strategy represents the only realistic near-term approach to studying ISOs in situ. While waiting times might seem like a disadvantage, the upcoming Vera C. Rubin Observatory and its Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST) should dramatically improve our ability to detect and characterize ISOs, potentially identifying 10 or more such objects over the next decade.

The Future of Interstellar Object Science

The white paper acknowledges that the 2029 Comet Interceptor mission itself has only a vanishingly small probability of encountering an interstellar object. The timing would need to be extraordinarily fortuitous: an ISO would need to be detected with sufficient lead time, follow a trajectory that brings it within reach of the spacecraft's propulsion capabilities, and arrive during the mission's operational window. Despite these long odds, the authors emphasize that CI serves as a crucial proof-of-concept for the wait-in-space approach.

Looking further ahead, the Rubin Observatory's systematic survey of the sky will revolutionize our understanding of the interstellar object population. Current estimates suggest that at any given time, several ISOs may be passing through the inner solar system, but most remain undetected due to their faintness and rapid motion. With its unprecedented combination of wide field of view and deep sensitivity, Rubin should detect ISOs weeks or even months before they reach their closest approach to the Sun, providing the advance warning necessary to plan an interception mission.

These detections will also help constrain the true population size and characteristics of interstellar objects. Are they predominantly icy comets like Borisov, rocky asteroids like 'Oumuamua, or a mixture of both? Do they show evidence of exotic compositions not found in solar system bodies? How common are active comets versus inert, asteroid-like objects? Answering these questions will help mission planners design optimal payloads and observation strategies for future ISO encounters.

Implications for Astrobiology and the Search for Life

Perhaps the most tantalizing aspect of studying interstellar comets involves their potential connection to the origin and distribution of life in the galaxy. Rosetta's detection of glycine, phosphorus, and complex organic molecules on 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko suggested that comets may have delivered the chemical ingredients for life to the early Earth. If similar organic compounds appear in comets from other stellar systems, it would suggest that the chemistry of life may be a universal phenomenon, arising naturally wherever conditions permit.

The discovery of amino acids or other prebiotic molecules in an interstellar comet would have profound implications for astrobiology. It would indicate that the chemical pathways leading to life operate similarly across different stellar environments, strengthening the case that life may be widespread throughout the galaxy. Conversely, finding significantly different organic chemistry might reveal alternative pathways to complexity that we haven't yet imagined.

"There is strong scientific and public interest in an ISO mission, and we believe that CI can act as a proof of concept for the 'wait in space' approach for such a mission, while achieving its own Solar System exploration goals."

A Realistic Path to Touching the Stars

The authors make a compelling argument that for the foreseeable future—and quite possibly forever—humanity will remain confined to our solar system. The distances between stars are simply too vast, and the energy requirements for interstellar travel too enormous, for crewed missions to other stellar systems to be practical with any conceivable technology. Even robotic probes would require centuries or millennia to reach even the nearest stars using current propulsion methods.

In this context, interstellar objects represent humanity's best—and perhaps only—opportunity to directly study material from other planetary systems. Rather than traveling to the stars, we can wait for pieces of them to come to us. Each ISO that passes through our solar system offers a unique window into the conditions and processes operating in a distant stellar system, information that would otherwise remain forever beyond our reach.

The white paper submitted to the UK Space Frontiers 2035 exercise makes a strong case that an interstellar object mission should be a high priority for the space science community. With the Comet Interceptor mission demonstrating the viability of the wait-in-space approach, and the Rubin Observatory poised to revolutionize ISO detection, all the pieces are falling into place for humanity's first close encounter with a visitor from the stars.

As we stand on the threshold of this new era in space exploration, the prospect of analyzing material from another stellar system—of holding in our instruments a piece of an alien world—transforms from science fiction to achievable reality. The next decade may well see the launch of a mission that will finally answer the question: how different, or how similar, are the building blocks of planetary systems across our galaxy? The answer promises to reshape our understanding of our place in the cosmic story.