The quest to establish a permanent human presence on the Moon faces an unexpected challenge that lies hidden in plain sight: the very dust beneath our feet. Recent groundbreaking research from the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) has revealed that ancient lunar soil—weathered by billions of years of cosmic bombardment—can completely mask the chemical signatures of valuable resources like titanium, potentially misleading our orbital surveys and complicating future mining operations. This discovery fundamentally alters how scientists must interpret data from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), one of humanity's most sophisticated tools for mapping lunar resources.

The phenomenon, known as space weathering, transforms the Moon's surface through relentless exposure to solar wind particles and micrometeoroid impacts. Unlike Earth, where atmospheric protection and geological processes constantly refresh surface materials, the Moon's airless environment preserves a detailed record of this cosmic assault. Over geological timescales, this weathering creates a layer of altered regolith that can confound even our most advanced remote sensing instruments, particularly those operating in the far ultraviolet (FUV) spectrum.

Published in a comprehensive study examining Apollo-era soil samples, the research demonstrates that the "age" of lunar regolith—measured by its exposure to space weathering—dramatically affects how it reflects ultraviolet light. This has profound implications for resource prospecting missions and the planning of future lunar bases, where accurate knowledge of subsurface composition could mean the difference between mission success and failure.

The Invisible Transformation: Understanding Space Weathering on the Moon

Space weathering represents one of the most significant surface modification processes occurring throughout our solar system. On the Moon, this phenomenon operates through two primary mechanisms: the constant stream of solar wind particles and the impact of microscopic meteoroids traveling at hypervelocity speeds. The Moon's lack of a protective atmosphere means these processes have been sculpting its surface for over 4.5 billion years, creating a complex layer of modified material that can reach depths of several meters.

The solar wind, a continuous outflow of charged particles from our Sun, bombards the lunar surface with ions traveling at speeds exceeding 400 kilometers per second. When these energetic particles strike lunar soil grains, they trigger chemical reactions that fundamentally alter the surface properties of individual particles. Simultaneously, micrometeoroid impacts—though individually tiny—collectively reshape the lunar surface through billions of years of accumulated damage, creating an increasingly roughened texture at microscopic scales.

Understanding these weathering processes is crucial for resource assessment because the Moon contains valuable materials essential for sustained human presence. Titanium, for instance, exists in significant concentrations in certain lunar regions and could be used for manufacturing structural components and equipment. Similarly, identifying water ice deposits, rare earth elements, and other resources requires accurate interpretation of remote sensing data—a task complicated by the masking effects of space weathering.

Decoding Ultraviolet Signatures: The LRO's Spectral Challenge

While infrared and visible light spectroscopy have dominated lunar resource mapping efforts, far ultraviolet spectroscopy offers unique insights into surface composition. The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, launched in 2009 and still operational, carries the Lyman Alpha Mapping Project (LAMP) instrument specifically designed to capture FUV data. This wavelength range, extending from approximately 115 to 190 nanometers, can reveal information about surface chemistry that other wavelengths cannot detect.

However, scientists analyzing LRO's FUV data encountered puzzling inconsistencies. Spectral signatures varied dramatically across different lunar regions in ways that couldn't be explained solely by differences in chemical composition. Some areas with known high concentrations of certain minerals appeared spectrally similar to regions with entirely different compositions. The SwRI research team hypothesized that these discrepancies stemmed from varying degrees of space weathering exposure—essentially, the "age" of the surface layer being observed.

To test this hypothesis, researchers obtained three Apollo soil samples with documented collection contexts. Two samples came from surface locations with billions of years of exposure to space weathering, while a third was collected from within a trench, representing relatively "fresh" material shielded from direct exposure. This experimental design allowed the team to isolate the effects of weathering age on FUV spectral properties.

Laboratory Analysis: Revealing the Nanoscale Iron Phenomenon

The research team employed cutting-edge analytical techniques, including scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and tunneling electron microscopy (TEM), to examine the soil samples at nanometer scales. These instruments revealed a striking transformation in the weathered samples: their surfaces were covered with countless nanoscale iron particles, each measuring just billionths of a meter across. The researchers dubbed this phenomenon "iron acne"—a vivid description of the pockmarked appearance created by these tiny metallic deposits.

These nanophase iron particles form through a fascinating process called vapor deposition. When solar wind ions strike iron-bearing minerals in lunar soil, they liberate iron atoms that then condense onto nearby grain surfaces. Over millions of years, this process coats mature lunar regolith with an increasingly thick layer of metallic iron nanoparticles. The fresh sample from the Apollo trench, by contrast, showed dramatically fewer of these particles, confirming that their abundance directly correlates with exposure duration.

"The surface roughness created by billions of years of micrometeoroid bombardment, combined with the accumulation of nanophase iron, fundamentally changes how these materials interact with ultraviolet light. What we're seeing in FUV observations is often more a measure of surface age than chemical composition."

The Brightness Paradox: How Light Scattering Reveals Surface Age

One of the study's most significant findings concerns how weathered and fresh regolith scatter ultraviolet light in fundamentally different ways. The relatively smooth surfaces of fresh lunar soil grains exhibit forward scattering—when FUV light strikes these particles, it bounces away from the light source, similar to how a mirror reflects light. This forward scattering makes fresh regolith appear approximately twice as bright in FUV wavelengths compared to weathered material.

Weathered regolith, with its rough, pockmarked surface texture, behaves entirely differently. The microscopic irregularities created by eons of micrometeoroid impacts cause backscattering, where light reflects back toward its source rather than bouncing forward. This backscattering effect, combined with the light-absorbing properties of nanophase iron, causes ancient regolith to appear significantly darker in FUV observations from orbit.

This discovery helps explain previously puzzling observations from the LCROSS mission and other lunar surveys, where surface brightness variations didn't always correlate with expected compositional differences. The age-dependent scattering behavior means that two regions with identical chemical compositions but different weathering histories will appear dramatically different in FUV imagery.

The Titanium Masking Problem: When Chemistry Becomes Invisible

Perhaps the most troubling implication of this research concerns resource identification. The study examined two heavily weathered Apollo samples from dramatically different lunar environments: one from a mare region (the dark volcanic plains visible from Earth) with high titanium content, and another from the lighter-colored highlands with much lower titanium concentrations. Despite their vastly different chemical compositions, these samples produced nearly identical FUV spectral signatures.

This masking effect poses serious challenges for lunar resource prospecting. Titanium oxide concentrations in mare basalts can exceed 10% by weight, making these regions potentially valuable mining sites. However, if space weathering obscures these chemical signatures in FUV data, scientists must rely on other wavelengths or ground-truth measurements to accurately assess resource distributions. The research suggests that for some critical resources, orbital FUV spectroscopy alone may be insufficient for detailed mapping.

Reconciling Laboratory and Orbital Observations

Interestingly, the laboratory findings initially appeared to contradict actual observations from LRO, which show that fresh lunar soil typically appears "redder" (relatively brighter at longer FUV wavelengths) than aged regolith—the opposite of what the controlled experiments suggested. The researchers propose several explanations for this apparent discrepancy, highlighting the complexity of real-world lunar surface conditions.

One factor involves the physical structure or "fluffiness" of undisturbed lunar soil. On the Moon's surface, regolith maintains an extremely loose, porous structure due to the absence of moisture and compaction forces. This structure affects light scattering in ways that cannot be perfectly replicated in collected samples, which inevitably undergo some compaction during collection and transport. The presence of shocked materials—grains that have been instantaneously heated and modified by micrometeoroid impacts—may also play a role in the spectral differences between laboratory samples and orbital observations.

Additionally, the European Space Agency's SMART-1 mission and other lunar orbiters have documented that surface texture varies considerably across different lunar terrains, influenced by factors such as slope angle, local geology, and impact history. These variations introduce additional complexity to spectral interpretation that extends beyond simple age-based weathering effects.

Implications for Future Lunar Exploration and Resource Utilization

As humanity advances toward establishing permanent lunar bases, accurate resource mapping becomes increasingly critical. The Artemis program aims to return humans to the Moon by the mid-2020s, with plans for sustained presence and eventual resource utilization. Understanding the limitations of current remote sensing techniques helps mission planners identify where additional ground-truth measurements are needed and how to interpret existing orbital data more accurately.

The research suggests several strategies for improving resource assessment:

- Multi-wavelength integration: Combining FUV data with infrared, visible light, and radar observations can provide a more complete picture of surface composition, with each wavelength offering complementary information

- Age mapping: Creating detailed maps of surface age based on crater density and other geological indicators can help scientists account for weathering effects when interpreting spectral data

- Targeted sampling: Future robotic missions should prioritize collecting samples from various depths and weathering states to build more comprehensive calibration datasets

- Advanced modeling: Developing sophisticated computer models that account for the complex interplay between composition, weathering, and spectral properties will improve interpretation accuracy

- In-situ analysis: Deploying rovers and landers equipped with direct analysis instruments can provide ground-truth measurements to validate and calibrate orbital observations

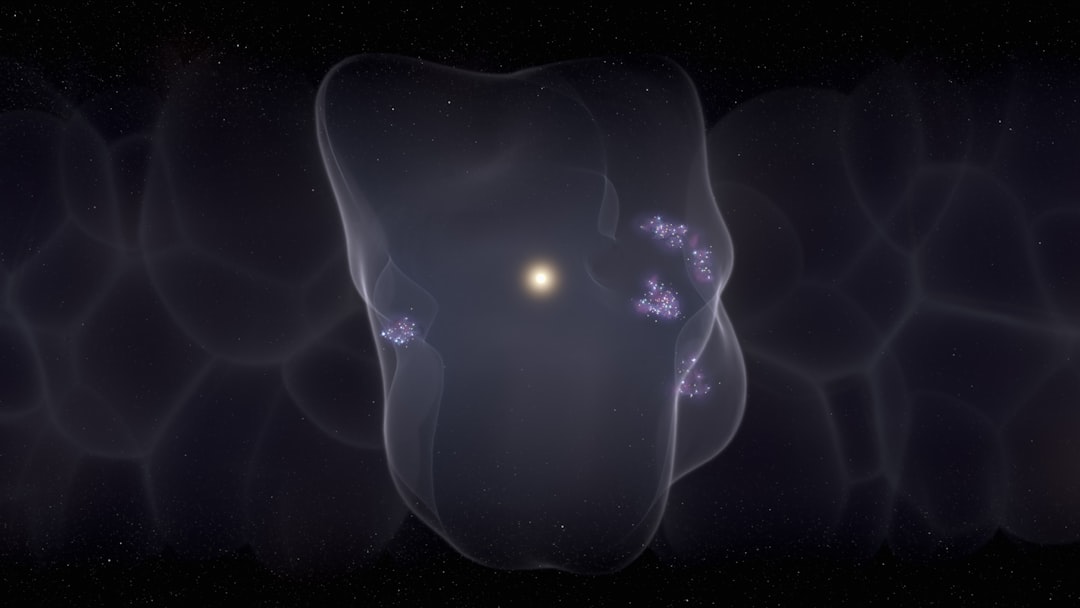

The Broader Context: Space Weathering Across the Solar System

While this research focuses specifically on lunar regolith, space weathering affects airless bodies throughout our solar system. Asteroids, the moons of Mars, and Mercury all undergo similar surface modification processes, though the specific mechanisms and rates vary depending on their distance from the Sun and local environmental conditions. Understanding these processes on the Moon—our nearest celestial neighbor and most accessible laboratory—provides insights applicable to future missions exploring more distant destinations.

The findings also have implications for interpreting observations of exoplanetary systems and debris disks around other stars. Dust grains in these distant environments undergo their own weathering processes, and understanding how such processes affect spectral signatures helps astronomers make more accurate inferences about the composition of materials in these far-flung systems.

Looking Forward: Next-Generation Lunar Science

Future lunar missions will build upon these findings with increasingly sophisticated instruments. Proposed rovers carrying ground-penetrating radar could map the three-dimensional structure of regolith layers, revealing how weathering effects vary with depth. Advanced spectrometers capable of measuring across broader wavelength ranges simultaneously will provide richer datasets for compositional analysis. Sample return missions to diverse lunar locations will expand our calibration library, improving our ability to interpret remote sensing data accurately.

The SwRI study underscores a fundamental principle of planetary science: the surfaces we observe from orbit are not simple windows into underlying composition but rather complex interfaces shaped by billions of years of environmental processes. As we prepare to return to the Moon and establish a sustained human presence there, this deeper understanding of how space weathering masks and modifies surface properties will prove invaluable for resource prospecting, site selection, and mission planning.

By accounting for the age and weathering state of lunar regolith in our resource assessments, we can develop more accurate maps of where valuable materials lie hidden beneath the ancient, weathered surface. This knowledge transforms our approach from simply looking at the Moon to truly understanding what we're seeing—and what might be concealed beneath that deceptively simple gray dust that has captivated human imagination for millennia.