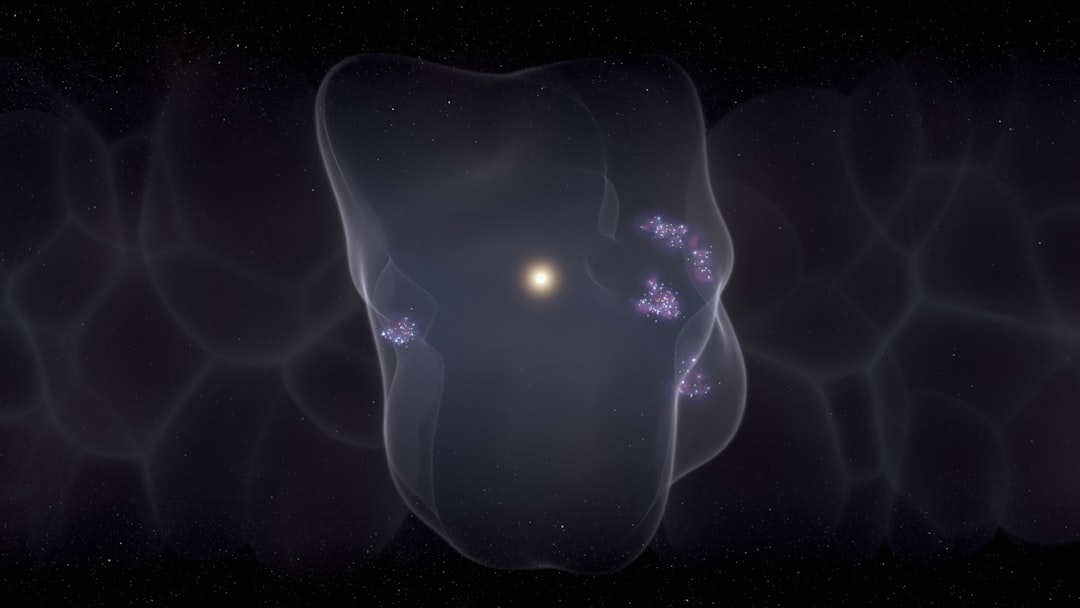

In the vast expanse of space, where traditional rocket fuel becomes a costly burden, solar sails have emerged as one of the most promising propulsion technologies for future space exploration. These elegant systems harness the momentum of photons from sunlight, eliminating the need for conventional propellant entirely. However, a fundamental challenge has plagued solar sail technology since its inception: how do you steer a spacecraft when there's no air for a rudder and every gram of equipment counts against your mission profile?

Now, researchers at the University of Pennsylvania have proposed an ingenious solution inspired by an ancient Japanese art form. In a groundbreaking pre-print paper published on arXiv, Gulzhan Aldan and Igor Bargatin describe a revolutionary steering mechanism based on kirigami—the traditional practice of strategic paper cutting. Their approach could fundamentally transform how we navigate spacecraft across the solar system and beyond, offering a low-power alternative to existing control systems that have limited the full potential of solar sail technology.

This innovation arrives at a critical moment in space exploration. As missions venture farther from Earth and mission durations extend from months to years or even decades, the efficiency of propulsion and control systems becomes paramount. The kirigami-based approach addresses multiple limitations simultaneously: it reduces power consumption, eliminates the need for propellant in steering mechanisms, and potentially increases the reliability of solar sail missions through elegant mechanical simplicity.

The Fundamental Challenge of Solar Sail Navigation

Unlike traditional maritime sailing vessels that operate in Earth's atmosphere, solar sails face unique constraints in the vacuum of space. On Earth's oceans, sailors have two primary control mechanisms at their disposal: adjustable sails that catch wind at varying angles, and rudders that redirect water flow to change the vessel's heading. These rudders exploit the resistance of water—a luxury unavailable in space where no medium exists to push against.

The physics of solar sailing relies on photon momentum transfer. When light particles strike a reflective surface, they impart a tiny but measurable force. Over time, in the frictionless environment of space, these minuscule forces accumulate to produce significant acceleration. The Planetary Society's LightSail missions have demonstrated this principle beautifully, proving that spacecraft can indeed "sail" on sunlight alone.

However, changing direction requires altering the angle at which photons strike and reflect from the sail surface. This seemingly simple requirement has spawned decades of engineering innovation, with each solution bringing its own set of compromises and limitations.

Traditional Steering Methods and Their Limitations

Engineers have developed three primary approaches to solar sail steering, each with distinct advantages and drawbacks that have shaped mission design decisions:

Reaction Wheels and Momentum Management

Reaction wheels represent the most common solution for satellite attitude control, including solar sail spacecraft. These devices consist of heavy flywheels that spin up or slow down to transfer angular momentum to the spacecraft body. When a reaction wheel accelerates in one direction, the spacecraft rotates in the opposite direction—a direct application of Newton's third law of motion.

While reliable and well-understood, reaction wheels impose significant penalties on solar sail missions. Their mass can constitute a substantial fraction of the total spacecraft weight, directly reducing the acceleration potential of the sail. More critically, they eventually require "desaturation"—a process where thrusters fire to reset the wheels' momentum, consuming precious propellant and partially negating the propellant-free advantage of solar sails.

Tip Vanes and Mechanical Complexity

A more recent innovation involves tip vanes—small, independently rotatable mirrors positioned at the corners of the solar sail. By adjusting these vanes' angles, engineers can create differential forces that torque the spacecraft in desired directions. This approach offers finer control than reaction wheels and doesn't require momentum desaturation.

However, tip vanes introduce mechanical complexity at the most vulnerable points of the sail structure. The deployment mechanisms, motors, and control systems needed for each vane create multiple potential failure points. In the harsh environment of space, where temperature extremes cycle from -270°C to +120°C and micrometeorite impacts pose constant threats, mechanical systems face significant reliability challenges. A single jammed vane could leave a spacecraft unable to properly orient itself, effectively ending the mission.

Reflectivity Control Devices

Perhaps the most sophisticated existing approach employs Reflectivity Control Devices (RCDs), which function similarly to e-reader displays. These liquid crystal panels can electronically switch between reflective and absorptive states, modulating how much photon momentum different sections of the sail capture. Japan's pioneering IKAROS mission, launched in 2010, successfully demonstrated this technology during its journey to Venus.

"The IKAROS mission proved that active control of solar sail reflectivity could enable precise attitude control without mechanical systems, opening new possibilities for long-duration missions," noted mission planners at JAXA.

Despite their elegance, RCDs carry a critical drawback: they require continuous electrical power to maintain their state. Even when not actively changing configuration, the liquid crystal systems draw current from the spacecraft's batteries. Over multi-year missions far from the Sun where solar panel efficiency drops, this constant power drain becomes increasingly problematic, potentially limiting mission duration or requiring larger, heavier power systems.

The Kirigami Revolution: Ancient Art Meets Space Engineering

Kirigami, derived from the Japanese words "kiru" (to cut) and "kami" (paper), represents a centuries-old artistic tradition of creating intricate designs through strategic cutting patterns. Unlike origami, which achieves three-dimensional forms through folding alone, kirigami employs cuts to enable more dramatic transformations of flat materials into complex 3D structures.

The Pennsylvania researchers recognized that this ancient principle could solve a thoroughly modern problem. Their kirigami solar sail design incorporates precisely engineered cuts into the sail material—typically aluminized polyimide film, an industry-standard substrate chosen for its excellent strength-to-weight ratio and reflective properties when coated with aluminum.

The Mechanics of Controlled Buckling

The innovation centers on creating a grid of "unit cells" across the sail surface, each containing carefully positioned cuts running in both axial and diagonal directions. When tension is applied to the film through servo motors at the edges, these cuts allow the material to undergo controlled mechanical buckling—essentially popping out of its flat plane to create a complex three-dimensional surface topology.

This buckling transforms the smooth sail into a landscape of tilted facets, each acting as a miniature mirror oriented at a specific angle. The genius of this approach lies in its tunability: by adjusting the tension applied to different regions of the sail, engineers can control the degree and pattern of buckling, thereby directing photon reflection in precise directions.

The physics governing this system follow directly from conservation of momentum. When photons strike a tilted surface and reflect at an angle, they impart momentum in a direction perpendicular to that surface. The sail experiences a force opposite to the direction of photon reflection. By creating thousands of tiny tilted surfaces across the sail, each contributing its vector of force, the system generates a net torque that rotates the spacecraft.

Rigorous Testing and Validation

To validate their revolutionary concept, Aldan and Bargatin employed both computational modeling and physical experimentation—a dual approach that strengthens confidence in the technology's viability.

Computational Simulation Results

The researchers utilized COMSOL Multiphysics, an industry-standard finite element analysis package widely used in aerospace engineering, to model the kirigami sail's behavior under various conditions. Their simulations incorporated ray tracing algorithms to track individual photon paths as they struck and reflected from the buckled surface.

By systematically varying both the buckling configuration and the angle of incident sunlight, the team mapped out the complete force landscape the sail would experience. The simulations revealed that each watt of sunlight striking the sail generates approximately 1 nanonewton (nN) of force—a seemingly infinitesimal amount. However, in the context of space propulsion, this tiny force becomes significant when applied continuously over weeks, months, or years.

To put this in perspective: a force of 1 nN applied to a 100-kilogram spacecraft for one year would change its velocity by approximately 0.3 meters per second. While modest, this represents the difference between maintaining a precise trajectory and drifting off course during a multi-year interplanetary mission.

Laboratory Demonstration

Moving from simulation to reality, the researchers conducted physical experiments in a controlled laboratory environment. They fabricated kirigami-patterned films and mounted them in a test chamber equipped with a precision laser system. By directing the laser beam at the film and systematically varying the tension applied to its edges, they could observe how the buckled surface redirected light.

The experimental results closely matched the computational predictions, with the reflected laser spot moving across the chamber wall in patterns that corresponded precisely to the theoretical angles of incidence for each strain level. This agreement between theory and experiment provides strong evidence that the kirigami approach will function as intended when deployed in space.

Advantages Over Existing Technologies

The kirigami steering system offers several compelling advantages that could make it the preferred choice for future solar sail missions:

- Power Efficiency: Unlike RCDs that require continuous power, kirigami sails only consume electricity when actively changing configuration. The servo motors used to adjust tension draw current only during repositioning maneuvers, potentially reducing total mission power requirements by orders of magnitude.

- Mechanical Simplicity: Compared to tip vanes with their complex deployment mechanisms and multiple articulation points, the kirigami approach relies on simple tension adjustment—a proven technology with high reliability in space applications.

- Scalability: The unit cell design allows the technology to scale from small CubeSat-class missions to enormous sails spanning hundreds of meters, with each cell operating independently to contribute to overall control authority.

- Graceful Degradation: If individual servo motors fail, the remaining functional units can compensate, unlike tip vane systems where a single stuck vane can severely compromise mission capabilities.

- Mass Efficiency: By eliminating heavy reaction wheels and complex vane mechanisms, more of the spacecraft's mass budget can be devoted to payload or additional sail area, improving overall mission performance.

Challenges and Future Development Path

Despite its promise, the kirigami solar sail concept faces several challenges before it can transition from laboratory demonstration to operational space mission. The cuts that enable controlled buckling also create stress concentration points where the material might tear under the constant tension required for deployment and operation. Long-term durability testing under simulated space conditions—including thermal cycling, vacuum exposure, and ultraviolet radiation—will be essential to validate the design's reliability over multi-year missions.

Additionally, the control algorithms required to coordinate potentially thousands of individual unit cells into coherent steering maneuvers represent a significant software engineering challenge. The system must respond to changing sun angles, account for the spacecraft's current orientation, and execute precise adjustments while compensating for the time delays inherent in photon-based propulsion.

Perhaps most significantly, the technology faces the classic challenge confronting all innovative space systems: limited flight opportunities. With solar sail missions remaining relatively rare compared to conventional spacecraft, competition for demonstration flights is intense. Organizations like NASA's Space Technology Mission Directorate and private entities are gradually expanding solar sail development, but the path from promising laboratory results to proven flight hardware typically spans a decade or more.

Implications for Future Space Exploration

If successfully developed and demonstrated, kirigami-based steering could enable entirely new classes of solar sail missions. The reduced power requirements would be particularly valuable for outer solar system exploration, where sunlight intensity drops dramatically and every watt of electrical power becomes precious. Missions to study the Sun's polar regions, maintain station-keeping at gravitationally unstable Lagrange points, or execute complex rendezvous maneuvers with asteroids or comets could all benefit from this efficient control system.

The technology might also prove valuable for emerging applications like space debris removal, where solar sails could provide the continuous, propellant-free thrust needed to deorbit defunct satellites. Similarly, constellations of kirigami-steered solar sails could serve as adjustable solar reflectors or sunshades, supporting ambitious climate engineering concepts or enabling solar power collection in space.

Looking further ahead, interstellar probe concepts like Breakthrough Starshot—which envisions laser-pushed lightsails reaching nearby star systems—might benefit from kirigami-based attitude control during the initial acceleration phase, ensuring optimal sail orientation as powerful ground-based lasers propel the craft to relativistic velocities.

Conclusion: A New Chapter in Solar Sailing

The marriage of ancient kirigami artistry with cutting-edge aerospace engineering exemplifies how innovation often emerges from unexpected connections between disparate fields. By reconceiving the solar sail not as a static reflector but as a dynamically reconfigurable surface, Aldan and Bargatin have opened new possibilities for efficient, reliable spacecraft control.

While considerable development work remains before kirigami sails grace actual space missions, the underlying physics is sound, and the engineering challenges appear surmountable. As humanity's ambitions in space continue expanding—from commercial satellite constellations to scientific missions exploring the outer reaches of our solar system—technologies that maximize efficiency while minimizing mass and power consumption will become increasingly valuable.

The kirigami solar sail stands as a testament to the power of interdisciplinary thinking and the ongoing evolution of space propulsion technology. When the first kirigami-steered spacecraft eventually deploys its intricately patterned sail and gracefully adjusts its course using nothing but the pressure of sunlight and the elegance of controlled buckling, it will represent not just a technological achievement, but a beautiful synthesis of human creativity spanning centuries and cultures.