The Moon's scarred and cratered surface conceals a hidden world of vast underground chambers and tunnels—ancient lava tubes formed billions of years ago when molten rock carved pathways through the lunar crust. These subterranean structures, along with deep vertical pits that puncture the surface, represent some of the most tantalizing targets for future lunar exploration. They offer natural protection from the harsh radiation bombardment and extreme temperature variations that make the Moon's surface so inhospitable to human habitation and scientific equipment.

Yet accessing these underground frontiers presents a formidable engineering challenge. The entrances to lunar caves are characterized by steep slopes, jagged rocks, and unstable regolith—the loose, dusty soil that blankets the Moon. Traditional small rovers, which are favored for lunar missions due to their lower cost and the ability to deploy multiple units as redundancy against failure, struggle with a fundamental physical limitation: their compact wheels cannot surmount obstacles significantly larger than their own diameter. This creates a critical dilemma for mission planners at organizations like NASA's Artemis program.

Now, an innovative team of researchers from South Korea has developed a revolutionary solution that draws inspiration from Renaissance engineering and the ancient Japanese art of paper folding. Their origami-inspired wheel can dramatically change its diameter on demand, offering small rovers the obstacle-clearing capabilities of much larger vehicles while maintaining a compact form factor for efficient transport and deployment.

The Underground Lunar Frontier: Why Lava Tubes Matter

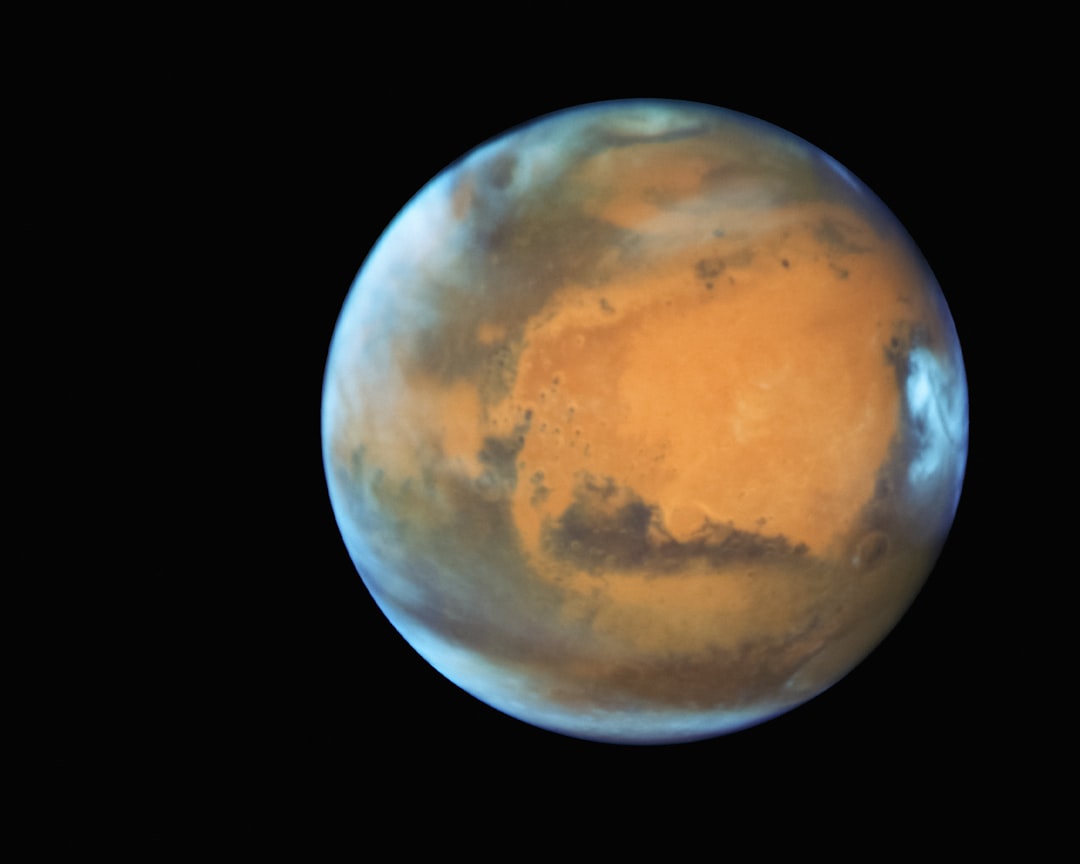

Before understanding the significance of this technological breakthrough, it's essential to appreciate why lunar lava tubes have captured the imagination of planetary scientists and mission planners worldwide. These natural tunnels, some potentially large enough to house entire cities, were formed during the Moon's volcanic past when rivers of molten basalt flowed beneath solidified crusts. When the lava drained away, it left behind hollow tubes—some estimated to be hundreds of meters wide and extending for kilometers beneath the surface.

Research from the Lunar and Planetary Institute suggests these structures could provide ideal locations for future lunar bases. The thick rock overhead would shield inhabitants and equipment from harmful cosmic radiation and solar particle events that constantly bombard the unprotected surface. Additionally, the stable underground environment maintains relatively constant temperatures, avoiding the wild swings between +127°C in sunlight and -173°C in shadow that characterize the lunar surface.

Beyond their practical value for human habitation, these caves represent pristine geological archives. Protected from micrometeorite impacts and space weathering, the exposed rock layers within lava tubes could preserve a detailed record of the Moon's volcanic history and potentially contain water ice deposits in permanently shadowed regions.

Engineering Challenges in the Lunar Environment

The Moon presents a uniquely hostile environment for mechanical systems, particularly those involving moving parts. Three factors make traditional rover designs especially problematic for lunar cave exploration:

- Abrasive lunar dust: The regolith consists of extremely fine, sharp particles created by billions of years of micrometeorite impacts. This dust infiltrates every crevice and acts like microscopic sandpaper on moving components.

- Cold welding: In the airless vacuum of space, metal surfaces that come into contact can spontaneously fuse together at the molecular level—a phenomenon that destroyed many mechanisms on early lunar missions.

- Extreme temperature cycling: Components must withstand temperature variations exceeding 300 degrees Celsius between the two-week lunar day and the equally long night, causing materials to expand and contract repeatedly.

- Radiation exposure: Without atmospheric or magnetic field protection, electronic components face constant bombardment from cosmic rays and solar radiation.

These challenges have historically made variable-geometry mechanisms nearly impossible to implement reliably on the lunar surface. Traditional hinges, joints, and actuators that work perfectly on Earth quickly fail in the lunar environment.

Da Vinci Meets Origami: A Joint-Free Solution

Professor Dae-Young Lee and his team at the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST) approached the problem from an entirely different angle. Rather than trying to protect traditional mechanical joints from the lunar environment, they eliminated joints altogether.

Their ingenious design draws upon two seemingly unrelated sources of inspiration. The first is Leonardo da Vinci's self-supporting bridge designs from the Renaissance, which used geometric arrangements to create stable structures without fasteners. The second is origami, the Japanese art of paper folding, which creates complex three-dimensional shapes through strategic folding patterns rather than cutting or gluing.

"By combining these ancient principles with modern materials science, we've created a wheel that transforms its geometry through elastic deformation rather than mechanical pivoting," explained Professor Lee. "This approach sidesteps the traditional failure modes that plague jointed mechanisms in the lunar environment."

The wheel consists of an elastic metal frame arranged in an origami-inspired pattern, with fabric tensioners that control the structure's expansion and contraction. When relaxed, the wheel maintains a compact diameter of 230 millimeters—small enough for efficient transport and low-profile operation on flat terrain. When the tensioners are engaged, the frame flexes outward, expanding the wheel to 500 millimeters in diameter, more than doubling its size and dramatically increasing its ability to climb over obstacles.

Rigorous Testing Under Simulated Lunar Conditions

The research team conducted extensive testing using lunar regolith simulant—materials engineered to match the physical properties of actual Moon dust. The results demonstrated several key advantages over conventional fixed-diameter wheels:

In traction tests on loose slopes, the expandable wheel showed superior grip compared to rigid wheels of equivalent size. The ability to increase surface area on demand provides better weight distribution across unstable regolith, reducing the likelihood of the rover becoming stuck or sliding backward on inclines.

Perhaps most impressively, the wheel survived drop tests simulating a 100-meter fall in lunar gravity. While this might seem extreme, it represents realistic scenarios for exploring the vertical pits that provide access to underground lava tubes. The elastic metal frame absorbed the impact energy through controlled deformation, then returned to its functional shape—a crucial capability for missions where repair is impossible.

Dr. Jongtae Jang from the Korea Aerospace Research Institute emphasized the thermal engineering involved: "We used detailed thermal models to optimize material selection and structural design. The wheel must maintain its elastic properties and structural integrity across the full temperature range encountered during lunar day-night cycles—that's a 300-degree Celsius span."

Scientific Implications and Mission Applications

Dr. Chae Kyung Sim from the Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute highlighted the broader scientific value of this technology: "Lunar pits and lava tubes are natural geological heritages that have remained largely inaccessible to robotic exploration. This wheel technology could finally bring these scientifically invaluable sites within our reach."

The implications extend beyond simple mobility improvements. The ability to deploy swarms of small, capable rovers rather than single large vehicles fundamentally changes mission risk profiles. If one rover in a swarm fails, others continue the mission. This redundancy is particularly valuable for cave exploration, where communication with Earth may be intermittent and rescue operations impossible.

Current lunar exploration programs, including ESA's lunar exploration initiatives and NASA's Commercial Lunar Payload Services program, could potentially integrate this technology into future missions. The wheels would enable rovers to navigate the challenging terrain around pit entrances, descend into caves, and explore the interior chambers while maintaining a compact profile for transport aboard lunar landers.

Remaining Challenges and Future Development

Despite this breakthrough, Professor Lee acknowledges that significant engineering challenges remain before the technology is mission-ready. Power systems must be optimized to operate the wheel transformation mechanism reliably in extreme cold. Communication systems need development to maintain contact with rovers exploring deep underground, where direct radio links to Earth or orbiting relay satellites may be blocked by hundreds of meters of rock.

The team is also working on integrating the wheels with advanced navigation systems that can operate in the complete darkness of cave interiors, where solar panels are useless and every watt of battery power is precious. Autonomous navigation capabilities will be essential, as the communication delays inherent in Earth-based control become impractical for navigating complex underground terrain.

Looking ahead, this origami-inspired wheel technology represents more than just a clever engineering solution—it exemplifies a broader trend in space exploration toward biomimetic and nature-inspired designs. By learning from natural systems and historical engineering principles, researchers are developing technologies that work with the extreme environments of space rather than fighting against them.

As international space agencies and private companies plan increasingly ambitious lunar missions, including permanent bases and resource extraction operations, technologies like this expandable wheel system will prove essential for accessing and utilizing the Moon's hidden underground resources. The ancient lava tubes that have remained sealed and pristine for billions of years may soon welcome their first robotic visitors, opening a new chapter in humanity's relationship with our closest celestial neighbor.