The pristine silence that radio astronomers depend upon to study the cosmos is under threat from an unexpected source. While much of the scientific community's attention has focused on the rapidly expanding constellations of low Earth orbit satellites, a comprehensive new study has turned its gaze upward—far upward—to examine a different population of space-based transmitters. At an altitude of 36,000 kilometers above Earth's surface, hundreds of satellites maintain their vigil in geostationary orbit, and until now, their potential impact on radio astronomy remained largely unmeasured and unknown.

A groundbreaking investigation led by researchers at CSIRO's Astronomy and Space Science division has provided the first systematic assessment of radio frequency interference from these distant orbital platforms. Using archival observations from the Murchison Widefield Array in Western Australia, the team analyzed 162 geostationary and geosynchronous satellites to determine whether they leak unintended radio emissions into frequencies critical for astronomical observation. The findings, which represent a crucial baseline for future radio telescope operations, offer cautious optimism for the next generation of astronomical instruments.

The Unique Challenge of Geostationary Satellites

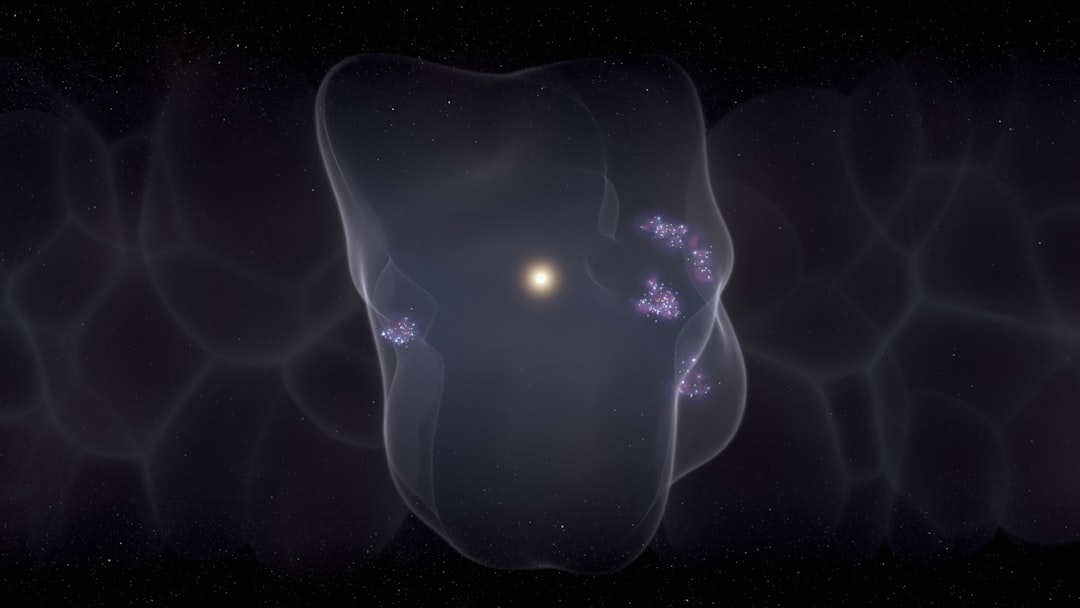

Geostationary satellites occupy a special place in both telecommunications infrastructure and astronomical concern. Unlike their low Earth orbit counterparts that race across the sky in mere minutes, these distant sentinels orbit at precisely the same rotational speed as Earth itself, appearing to hover motionlessly above a fixed point on the planet's surface. This orbital synchronization occurs at the specific altitude where gravitational force and centrifugal acceleration achieve perfect balance—approximately 35,786 kilometers above the equator.

This unique positioning makes geostationary satellites invaluable for telecommunications, weather monitoring, and military applications. A single satellite can maintain constant coverage over roughly one-third of Earth's surface, eliminating the need for complex handoffs between multiple spacecraft. However, this same characteristic presents a distinct challenge for radio astronomy: these satellites can remain within a radio telescope's field of view for extended periods, potentially contaminating observations for hours rather than seconds.

The geostationary belt hosts a diverse population of spacecraft handling everything from direct-to-home television broadcasts to secure military communications. According to the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs, hundreds of active satellites currently occupy this orbital zone, with more launches planned annually. Each represents a potential source of radio frequency interference, yet prior to this study, no comprehensive survey had measured their actual emissions in the low-frequency bands crucial for next-generation radio astronomy.

Pioneering Methodology: Measuring the Invisible

The research team employed an innovative approach using archival data from the GLEAM-X survey, captured by Australia's Murchison Widefield Array during observations conducted in 2020. This radio telescope, located in one of the most radio-quiet regions on Earth, provided an ideal platform for detecting faint emissions from distant satellites. The researchers focused their analysis on frequencies ranging from 72 to 231 megahertz—the same low-frequency band where the upcoming Square Kilometre Array will conduct its revolutionary observations.

The methodology required sophisticated image processing techniques. For each satellite, the team calculated its predicted position in the sky throughout the observation period, then "stacked" multiple images at those precise coordinates. This co-adding technique dramatically improved sensitivity, allowing the detection of even intermittent or weak radio emissions that would be invisible in individual snapshots. The approach essentially turned the satellite's constant presence in the field of view—normally a disadvantage—into an analytical strength.

"By stacking observations at the predicted satellite positions, we could achieve sensitivity levels that would reveal radio leakage at power levels far below what individual snapshots could detect. This technique is particularly powerful for geostationary satellites, which remain in our field of view throughout the observation period."

The observation strategy itself was carefully designed. By pointing the telescope near the celestial equator, where geostationary satellites cluster, the researchers ensured maximum exposure time for each target. This geometric advantage, combined with the Murchison Widefield Array's exceptional sensitivity and wide field of view, created ideal conditions for detecting even the faintest unintended emissions.

Remarkable Findings: A Quiet Neighborhood

The results of this comprehensive survey offer encouraging news for the astronomical community. The vast majority of geostationary satellites examined showed no detectable radio emissions in the studied frequency range. For most spacecraft, the research team established upper limits better than 1 milliwatt of equivalent isotropic radiated power within a 30.72 megahertz bandwidth—an impressively stringent constraint that speaks to both the satellites' design and the study's sensitivity.

The most stringent limits reached an exceptional 0.3 milliwatts, representing some of the tightest constraints ever placed on unintended satellite emissions in this frequency range. To put this in perspective, this power level is roughly equivalent to a tiny LED indicator light, yet spread across a bandwidth of over 30 megahertz and radiating in all directions from 36,000 kilometers away.

The Lone Exception

Among the 162 satellites surveyed, only one—Intelsat 10-02—showed possible detection of unintended emission, registering at approximately 0.8 milliwatts. Even this potential culprit remained well below typical emission levels observed from low Earth orbit satellites, which can radiate hundreds of times more powerfully. The Intelsat 10-02 finding requires further investigation to confirm whether the detection represents genuine satellite emission or a statistical artifact, but even if confirmed, it would represent a remarkably clean result for the geostationary population as a whole.

The contrast with low Earth orbit satellites is striking and informative. Recent studies of Starlink and other LEO constellations have documented much stronger unintended emissions, sometimes exceeding regulatory limits by substantial margins. The difference likely stems from both distance and satellite design philosophy—geostationary communications satellites, being far more expensive and serving critical infrastructure roles, may receive more rigorous electromagnetic compatibility testing during development.

Implications for the Square Kilometre Array

These findings carry profound significance for the Square Kilometre Array (SKA), the most ambitious radio astronomy project ever undertaken. When completed, SKA will be orders of magnitude more sensitive than current instruments in the low-frequency range, capable of detecting radio signals from the cosmic dawn—the era when the first stars and galaxies formed over 13 billion years ago.

What appears as harmless background noise to today's telescopes could become devastating interference for SKA's exquisitely sensitive receivers. The new measurements provide crucial baseline data for predicting and mitigating future radio frequency interference. They also establish a reference point against which future measurements can be compared, enabling astronomers to track whether the radio environment deteriorates as satellite technology evolves and orbital traffic increases.

Key Implications Include:

- Baseline Establishment: The study provides the first comprehensive baseline for geostationary satellite emissions in SKA-Low's operating frequencies, enabling future monitoring of changes in the radio environment

- Risk Assessment: Current geostationary satellites pose minimal threat to low-frequency radio astronomy, allowing more focused mitigation efforts on other interference sources

- Design Validation: The results validate that existing satellite design practices and regulatory frameworks are largely effective at preventing low-frequency radio leakage

- Future Planning: The methodology developed can be applied to monitor new satellites as they enter geostationary orbit, providing early warning of potential interference sources

The Physics of Distance: Why Location Matters

The relatively benign impact of geostationary satellites compared to their low Earth orbit counterparts can be understood through fundamental physics. Radio signal strength follows the inverse square law—doubling the distance reduces received power by a factor of four. Geostationary satellites orbit approximately ten times farther from Earth than the International Space Station's altitude of roughly 400 kilometers. This tenfold increase in distance translates to a hundredfold reduction in signal strength reaching ground-based telescopes.

Moreover, the geometry of geostationary orbits works in astronomers' favor. These satellites cluster near the celestial equator, allowing radio telescopes to avoid the most contaminated regions of sky when observing targets at higher celestial latitudes. Deep sky objects of interest—distant galaxies, quasars, and cosmic microwave background fluctuations—are distributed across the entire sky, giving astronomers flexibility in scheduling observations to avoid the geostationary belt when necessary.

The Broader Context: An Evolving Radio Environment

This study arrives at a critical moment in the history of radio astronomy. The proliferation of satellite constellations, particularly in low Earth orbit, has accelerated dramatically in recent years. SpaceX's Starlink constellation alone plans to deploy tens of thousands of satellites, while competing systems from OneWeb, Amazon's Project Kuiper, and others will add thousands more. Each satellite, regardless of its intended purpose, generates radio frequency emissions through various mechanisms.

Even satellites designed to avoid certain protected astronomical frequencies can leak unintended emissions through electrical systems, solar panels, and onboard computers. These emissions, termed "out-of-band" or "spurious" radiation, result from imperfect shielding, harmonic generation in electronic circuits, and other unavoidable engineering compromises. As satellite technology evolves—incorporating more powerful transmitters, complex digital processing systems, and higher data rates—the potential for increased radio frequency interference grows correspondingly.

The pristine radio quiet that astronomers have long relied upon is slowly vanishing. Radio astronomy requires some of the most sensitive receivers ever built, capable of detecting signals billions of times weaker than a cell phone transmission. The International Telecommunication Union has established protected frequency bands for radio astronomy, but enforcement remains challenging, and unintended emissions often fall outside regulatory frameworks designed primarily for intentional transmissions.

Looking Forward: Preservation and Coexistence

The encouraging results for geostationary satellites demonstrate that careful engineering and appropriate regulatory frameworks can enable peaceful coexistence between space-based telecommunications and ground-based astronomy. However, maintaining this status quo will require ongoing vigilance and cooperation between satellite operators, regulatory bodies, and the astronomical community.

Several strategies are emerging to address the broader challenge of satellite interference. These include improved satellite shielding, more stringent testing protocols, real-time interference monitoring systems, and sophisticated signal processing techniques that can identify and subtract satellite contamination from astronomical data. Some researchers are even exploring the possibility of establishing radio-quiet zones in space itself—orbital regions where satellite operations would be restricted to protect astronomical observations.

The methodology pioneered in this study—systematic monitoring of satellite emissions using existing radio telescope data—provides a template for ongoing surveillance. As new satellites enter geostationary orbit and existing spacecraft age, continued monitoring will reveal whether the currently benign situation persists or deteriorates. Early detection of emerging interference sources will enable proactive mitigation before problems become severe enough to compromise major astronomical facilities.

For now, geostationary satellites appear to be respectful neighbors in the low-frequency radio spectrum. Whether they remain so as technology evolves, orbital traffic increases, and radio telescopes grow ever more sensitive remains an open question—one that this pioneering study has equipped astronomers to answer through continued monitoring and analysis. The cosmic whispers that radio astronomers seek to detect are faint indeed, and preserving the ability to hear them will require sustained effort from all stakeholders in Earth's orbital environment.