The enigma of life's origins on Earth has captivated scientists for generations, standing as one of the most profound questions in all of science. While paleontological evidence indicates that microbial life emerged more than 4 billion years ago during Earth's tumultuous early history, the precise mechanisms by which lifeless chemistry transformed into living biology remain tantalizingly elusive. A groundbreaking new hypothesis from an international collaboration of researchers now proposes an innovative answer: perhaps the crucial first steps toward life occurred not in primordial soups or deep-sea vents, but within surface-bound prebiotic gels—sticky, protective matrices that could have served as nature's first laboratories for biochemical innovation.

This revolutionary "gel-first" hypothesis challenges conventional thinking about abiogenesis by suggesting that gel-like structures provided the essential scaffolding and protective environment necessary for organic molecules to concentrate, interact, and eventually organize into self-replicating systems. Published in the prestigious journal ChemSystemsChem, this research offers fresh perspectives on how scientists might search for life beyond Earth, particularly on worlds like Saturn's moon Titan and the icy satellites of Jupiter, where similar gel formations could harbor exotic biochemistries.

The Persistent Mystery of Abiogenesis

Understanding how inorganic matter transitioned to organic life represents one of science's greatest intellectual challenges. The scientific community broadly accepts that Earth's earliest inhabitants were simple, single-celled organisms that eventually developed sophisticated capabilities like photosynthesis and sexual reproduction over billions of years of evolution. These primitive life forms ultimately gave rise to the spectacular diversity of multicellular organisms, plants, and animals that populate our planet today. However, the critical question of how non-living chemical compounds first assembled into the complex, self-replicating molecular machinery characteristic of life remains frustratingly unresolved.

Traditional abiogenesis theories have focused primarily on the chemistry of individual biomolecules—amino acids, nucleotides, and lipids—and how these building blocks might have polymerized into proteins, RNA, and primitive cell membranes. Famous experiments like the Miller-Urey experiment of 1952 demonstrated that organic compounds could form spontaneously under conditions thought to resemble early Earth's atmosphere. Yet a significant gap persists between producing simple organic molecules and achieving the integrated, self-sustaining chemical systems that define living organisms.

A Revolutionary Gel-Based Framework for Life's Emergence

The innovative research team, led by Dr. Ramona Khanum from the Space Science Center (ANGKASA) at Malaysia's National University, brings together expertise from multiple disciplines spanning microbiology, astrobiology, physical chemistry, and materials science. Their collaboration includes scientists from the Institute of Microengineering and Nanoelectronics at UKM, the University of Duisburg-Essen in Germany, Hiroshima University's Office of Research and Academia-Government-Community Collaboration, and the University of Leeds in the United Kingdom.

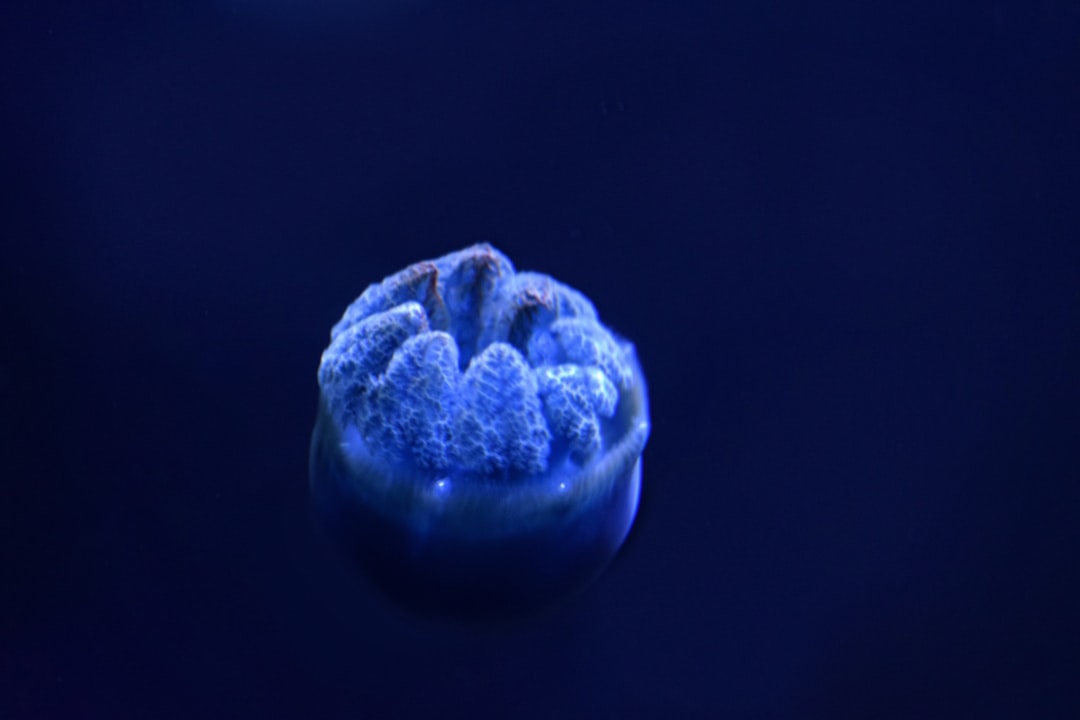

Their prebiotic gel hypothesis draws inspiration from modern biological systems, particularly microbial biofilms—those slimy bacterial communities that form on rocks in streams, coat the surfaces of ponds, and even develop on our teeth. These contemporary gels demonstrate remarkable properties: they concentrate nutrients, protect microorganisms from environmental stresses, facilitate chemical communication between cells, and create microenvironments with distinct chemical gradients. The research team proposes that similar gel-like structures, formed from simpler prebiotic chemistry, could have provided analogous benefits to emerging proto-life systems billions of years ago.

"While many theories focus on the function of biomolecules and biopolymers, our theory instead incorporates the role of gels at the origins of life. This represents a significant paradigm shift in how we conceptualize the transition from chemistry to biology," explained Professor Tony Z. Jia, a co-author on the study from Hiroshima University.

How Prebiotic Gels Could Have Catalyzed Life

The functional advantages of gel matrices for prebiotic chemistry are substantial and multifaceted. First, gels excel at molecular concentration—they can trap and accumulate organic compounds from dilute solutions, bringing reactive molecules into close proximity where they're more likely to interact productively. This addresses a fundamental problem in prebiotic chemistry: in vast oceans or atmospheric systems, potentially reactive molecules would typically be too dispersed to interact efficiently.

Second, these structures provide selective retention and filtering capabilities. Like a molecular sieve, gels can preferentially retain certain types of molecules based on size, charge, or chemical properties while allowing others to pass through. This selective permeability could have facilitated the emergence of increasingly complex chemical systems by concentrating useful compounds while excluding interfering substances.

Third, gels offer crucial environmental buffering. The gel matrix can shield delicate chemical reactions from harsh external conditions—protecting against destructive UV radiation, moderating pH fluctuations, and maintaining stable microenvironments even as surrounding conditions vary. This protective function would have been especially valuable on early Earth, which lacked the ozone layer and stable climate that shield modern life.

Key Advantages of the Gel-First Model

- Molecular Concentration: Gel matrices can accumulate organic compounds from dilute environments, increasing reaction rates by bringing molecules into close proximity—a critical factor for complex chemistry to emerge from sparse prebiotic conditions

- Structural Organization: The three-dimensional architecture of gels provides spatial organization that could have facilitated the development of proto-metabolic pathways, creating distinct chemical zones and gradients within a single gel structure

- Protection from Environmental Stress: Gel encapsulation shields sensitive chemical reactions from destructive UV radiation, extreme temperature fluctuations, and other harsh conditions prevalent on early Earth

- Selective Permeability: Like primitive cell membranes, gels can selectively retain beneficial molecules while allowing waste products or interfering compounds to diffuse away, enabling increasingly sophisticated chemical systems

- Surface Adhesion: By forming on mineral surfaces, these gels could have benefited from catalytic properties of rocks and minerals while remaining stable against water currents and environmental disturbances

Implications for Astrobiology and the Search for Extraterrestrial Life

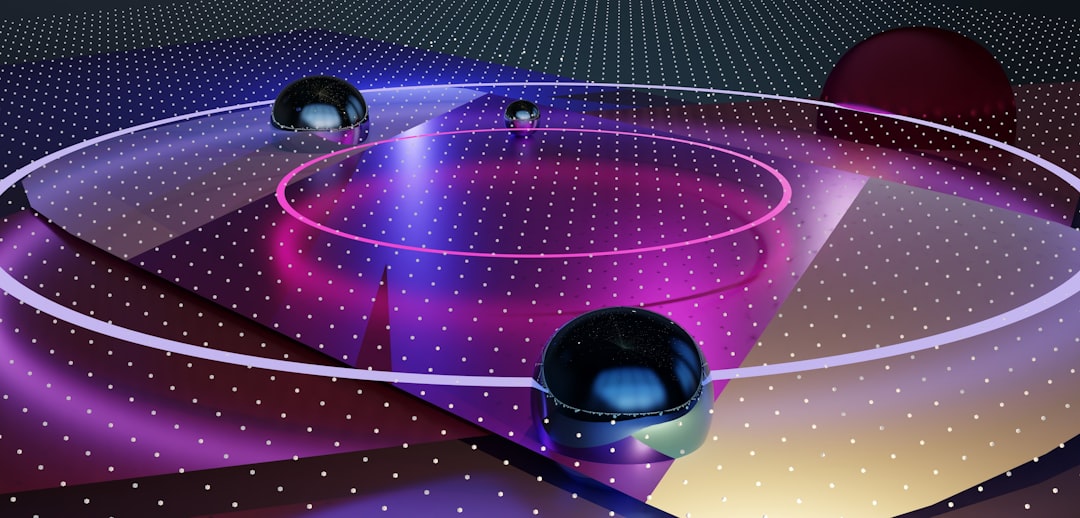

Perhaps the most exciting aspect of this research lies in its astrobiological implications. If life on Earth began within gel matrices rather than requiring specific biomolecules, then the search for life elsewhere in our solar system—and beyond—might need to broaden its focus. Rather than looking exclusively for Earth-like biochemistry based on DNA, RNA, and proteins, scientists could search for "xeno-films"—gel-like structures that might host entirely different forms of chemistry leading to alternative biochemistries.

This paradigm shift is particularly relevant for upcoming space missions. The European Space Agency's JUICE mission (Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer) and NASA's Europa Clipper will explore Jupiter's moons Ganymede and Europa beginning in the early 2030s. Both moons harbor vast subsurface oceans beneath their icy shells, and scientists speculate that hydrothermal activity on their seafloors could provide energy for life. The presence of gel-like structures within ice fractures or at ocean-ice interfaces could indicate active prebiotic chemistry or even primitive life forms.

"This is just one theory among many in the vast landscape of origin-of-life research. However, since the role of gels has been largely overlooked, we wanted to synthesize scattered studies into a cohesive narrative that puts primitive gels at the forefront of the discussion," noted Kuhan Chandru, a research scientist at Malaysia's Space Science Center.

Titan: A Prebiotic Laboratory in Our Solar System

Perhaps no destination offers greater promise for testing the gel hypothesis than Titan, Saturn's largest moon. This remarkable world possesses a thick nitrogen atmosphere, lakes and seas of liquid methane and ethane, and a rich inventory of organic compounds raining down from its hazy skies. NASA's upcoming Dragonfly mission, scheduled to arrive at Titan in 2034, will deploy a rotorcraft lander to explore multiple sites across this alien landscape.

Titan's complex organic chemistry makes it an ideal natural laboratory for studying prebiotic processes. The moon's surface features organic dunes, hydrocarbon lakes, and a subsurface water ocean—providing multiple environments where gel-like structures might form. If prebiotic gels played a role in Earth's life origins, Titan might host similar structures composed of exotic chemistry adapted to its frigid, methane-rich environment. Dragonfly's sophisticated instrument suite could potentially detect such formations, providing unprecedented insights into alternative pathways toward life.

Future Research Directions and Experimental Validation

The research team's next steps involve rigorous experimental validation of their hypothesis. They plan to investigate how prebiotic gels might have spontaneously formed from simple chemical precursors under conditions matching Earth's late Hadean eon, approximately 4 billion years ago. This period, which followed the massive bombardment that scarred the Moon and likely Earth, represents the earliest time when conditions might have been stable enough for life to emerge.

Laboratory experiments will explore several key questions: What chemical compositions could form stable gels under prebiotic conditions? How do these gels concentrate and organize organic molecules? Can gel-entrapped chemical systems develop autocatalytic (self-accelerating) reactions that might represent proto-metabolic processes? Do gels facilitate the polymerization of simple molecules into more complex structures? And critically, under what conditions might gel-based chemical systems transition toward genuinely living, self-replicating entities?

Dr. Khanum expressed optimism about the broader impact of their work: "We also hope that our work inspires others in the field to further explore this and other underexplored origins-of-life theories! The question of life's origins demands diverse approaches and creative thinking."

Connecting Ancient Gels to Modern Biology

An intriguing aspect of the gel-first hypothesis is how it might connect to modern cellular life. Today's cells contain numerous membrane-less organelles—specialized compartments that lack the lipid boundaries surrounding most cellular structures. These organelles, formed through a process called liquid-liquid phase separation, create distinct chemical environments within cells much like gels do. Some researchers speculate that these structures might represent evolutionary descendants of prebiotic gels, suggesting a direct lineage from Earth's earliest chemical systems to sophisticated modern cells.

The cytoplasm of modern cells itself exhibits gel-like properties, with its complex mixture of proteins, nucleic acids, and other molecules creating a structured environment quite different from simple aqueous solution. This raises the fascinating possibility that life didn't so much emerge from gels as it emerged as a gel—with the gel matrix itself evolving into the organized interior of living cells.

Broader Significance for Understanding Life's Universality

This research contributes to fundamental questions about life's inevitability in the universe. If life requires highly specific conditions and precise sequences of unlikely chemical events, it might be extraordinarily rare. However, if simple physical-chemical processes like gel formation can naturally concentrate and organize molecules in ways that lead toward life, then the emergence of biology might be a more common outcome of planetary chemistry than previously thought.

The gel hypothesis suggests that life-friendly environments might be more common and diverse than traditional theories predict. Rather than requiring specific volcanic vents, tidal pools, or atmospheric conditions, life could potentially begin wherever conditions allow gel formation—a much broader set of circumstances that might exist on countless worlds throughout the cosmos.

As humanity's exploration of the solar system intensifies and our catalog of exoplanets grows, frameworks like the prebiotic gel hypothesis will prove invaluable for guiding our search for life beyond Earth. By expanding our conception of how life can begin, we expand the range of environments we recognize as potentially habitable—and increase our chances of finally answering the profound question: Are we alone in the universe?